Emma Ardinghi, my great-grandmother, animated by deep-fake technologies. She was born in the 1860s and died in the 1930s. Not many of us have images of their ancestors of more than a century ago. But what if some ultra-advanced technology could show your ancestors all the way to back to the creation of the world? (image created on this site. To know more about Emma, see here.) (this post was originally published on "The Proud Holobionts")

Let's imagine a magic trick, or maybe a time machine, or a DNA-reconstructing technology, or some unknown laws of physics. Something, anyway, that shows you your ancestresses, all of them, one by one in a long, long string of mothers that leads you far, far back in time, all the way to the beginning of life on Earth. You are looking maybe into a screen, maybe into a crystal ball, or maybe into the clear waters of a stream in the light of the Moon. Just imagine.

Ten Generations (250 years). This stream of ten generations lasts ten minutes, one minute for each ancestress. The first face is our mother, of course. You know her well. You see her as a young woman, as you saw her in many old photos. Then, there appears your Grandmother, again as a young woman. Maybe you met her, maybe you remember her only from some faded pictures. She looks a little like you, same skin color and same eyes. As new images appear you see faces you had never seen and the parade stops with the face of a woman who is your ancestor of 10 generations ago. She was born around 250 years before you, in a century when almost everyone was a peasant and there existed no such things as electricity, cars, or radio and tv. She has the same skin color as you, the same shape of eyes and nose, and probably a similar hair color. Let's assume that she is from Europe or North America and, in this case, she is most likely white. She wears a long cotton skirt and a shirt under a wool corset. She also wears a head cap and wooden sandals, no makeup on her face, her only ornament is a hairpin that she uses to keep her hair in a bun. She looks strong, in good physical shape, not a trace of fat on her body. Her husband appears behind her, a peasant wearing simple clothes and wooden sandals. In the background, you see the brick walls of the house. The windows are small and have wooden shutters. In a corner, a large fireplace. Although she is linked to you by a series of ten generations, her genetic imprint on you has been so diluted that she doesn't look very much like you. Still, if you look into her eyes, you feel a certain kindness, a certain sensation of familiarity. From wherever the image comes from, she locks her eyes into yours and smiles before fading.

100 Generations (2000 years). Now the images change on the screen every six seconds. In ten minutes you see a hundred ancestresses, one after the other, separated by about 20 years from each other. Tall and not so tall, with long hair, short hair, sturdy, thin, lean, smiling, or maybe sad. There is a certain continuity with these images, the skin color remains about the same as yours: if you are black, they are black, and if you are white, they are white. And if you have slant eyes, they have slant eyes, too. But if you are blond, or you have clear-colored eyes, you'll see this feature disappearing: the eyes of your ancestresses gradually becoming brown, and their hair turns dark brown or black. When you arrive at the end of the sequence, you see someone who lived around 2000 years ago, at the time of the Roman Empire in its highest glory. She looks sturdy, but a little worn out by work and fatigue. She may wear a linen tunic under a heavy woolen cape. She may be a citizen of a large city, or someone inhabiting a small village. Behind her, her husband shows up. He is wearing similar clothes, a tunic, and a woolen mantle. Behind them, a brick wall with no windows, a fireplace in a corner. You perceive a simple wooden bed and a door. She doesn't look very much like you but, as you look into her face, you note a certain fire in her dark eyes. She is proud to be a citizen of the city or of the village where she lives. She smiles with an air of satisfaction at seeing that remote descendant of hers. For a moment, you are lost in those black eyes of her, then she fades away, and the parade restarts.

1000 generations (15 thousand years). Now the faces flash even faster, less than one second after each other. You see flickering faces, giving you just a quick glance of a few details: a hairpin, earrings, and an especially bright smile. These women maintain the same skin color you have and the same eye shape. But they look robust and sturdy, in good physical shape. The flickering stops with a woman appearing in front of you, looking straight at you. Let's assume that she is white. She wears a jacket and a gown in tanned skin. Around her neck, a leather necklace with hanging ivory teeth, maybe of a shark. Her hair is black, kept together by a leather lace at the back. Around her, you perceive a hut made of animal skin, mammoth tusks planted vertically in the soil are holding the skins together and a fire is burning at the center. Behind her, you see her husband. He wears the same kind of leather clothes and you see a stone-tipped lance leaning against the leather wall. You can almost smell the burned fat of the animals in the hut. You look at her face. She doesn't look like you, not at all. But she has a certain air of pride that you recognize as universal among humans. She smiles at you, she seems to be happy to see this descendant of hers that she sees for such a short time. Then, she fades away.

10,000 generations (150,000 years). It is a whirl of faces that you see dancing on the screen. What you notice most is how the skin of your ancestresses is becoming darker and darker. As the movement stops, you are looking into the face of a black woman. She has curly brown hair, black eyes looking straight into yours. She is tall, she looks athletic. She wears a necklace made with seashells and she wears only a leather belt around her waist as she stands in the bright sun. You know that she is living somewhere in Africa and, behind her, you see the blue of the Ocean. In the distance, the savannah extends all the way to the horizon. Around her, you see stones arranged in circles, traces of a campground where she lives, together with her group. You see her man standing behind her. Like her, he is tall and athletic, wearing only a leather belt around his waist. He holds a stone-tipped spear in his hands. An abyss of time separates you from her, and yet, somehow you recognize each other. You look into her eyes, she looks into yours. She smiles, although she looks a little perplexed at seeing this weird descendant of hers, so remote from her. But she seems to know that her descendants will cross that vast desert, spreading in the Northern forests and everywhere on Earth. She smiles at you as she says something that you don't understand, but that may be a charm of good luck. You smile back as she fades away.

100,000 generations. (one million years). What you see now is a continuous transformation, a morphing. The faces of your ancestresses change, shrink, their bones shift, they develop a pronounced brow ridge. Their skin remains dark, and when the sequence stops, you are in front of the face of this remote ancestress of yours, separated from you by one million years. You see her standing in the open, among rocks and animal bones. She is completely naked, her skin mostly hairless. She is not tall, but not so much shorter than you. Behind her, a flat savannah's landscape with shrubs and isolated trees. She is different, alien, with her broad nose, her flat skull under her black, long hair. You know that she is a member of the species called "homo erectus," not the same species you belong to, and you are tempted to call her "female," rather than "woman." And yet, she partakes something of the human nature, you can't miss that. She has round breasts, and rounded buttocks, a human trait that other primates do not share. Nearby, you see her man, holding a hand axe in his hands. She is linked to you by an incredibly long series of motherhoods, each one an improbable event, and yet that chain led exactly to you. You think for a moment at how a hundred thousand times a man and a woman, your ancestors, mated to generate the unlikely series of creatures that led to what you are. You look at each other in the eyes. Across a huge chasm of millennia, she nods at you, smiling, a gesture unchanged over such a long time. Then, she fades away

One million generations (10 million years). Now you are rushing to the remote origins of the creatures we call "hominina." As the face morphs in front of you, gradually it becomes something not fully human. The sequence stops as you are in front of a face. Still a face, yes, but not the face of a sapiens. You are looking at a female of a different species. She is hairy, small, and sitting in a forested area together with other members of her group. The male is bigger than her, and he looks suspiciously in your direction. You know that these creatures are common ancestors not just to you, but also to chimpanzees and gorillas. She looks at you, tilting her head a little as if she were surprised. You smile at her, she does not respond in kind, but she smacks her lips in your direction. A kiss from an ancestress of you who lived 10 million years ago. Then, the image fades away.

Ten million generations (100 million years). Now the creatures you see morphing on the screen rapidly cease having a face, they now have a snout. You see furry creatures quivering on the screen. The sequence stops to give you a glimpse of a four-footed creature that looks at you, puzzled, for a moment, before scuttling away, disappearing among the vegetation. Was that your ancestress? Yes, she was.

A hundred million generations (400 million years). Creatures smaller and smaller appear on the screen, they rapidly lose their fur, they become flat, lizard-like animals. Smaller and smaller, until they disappear and you are facing the seashore from an empty beach in the sun. You know that somewhere, under the surface, a female creature is swimming. An extremely remote ancestress of yours.

Billions of generations (one billion years ago). You are still looking at the sea. An ocean of time goes by and nothing happens. You only know that, down there, there is something alive, quivering, changing. Microscopic unicellular creatures are busy reproducing themselves by mitosis, splitting themselves in two. They are no more males and females, yet they are the origin of what you are, there, below the surface of that remote ocean.

Billions and billions of generations (5 billion years ago). Now the view moves underwater. In the darkness, you dimly perceive submarine mountains spewing gas bubbles everywhere. You know that those mounds are the factories where organic life is being created. It is strange to think that your so-remote ancestor is not anymore a living creature, but an organic molecule. As you watch, the sea boils in a great turmoil as you enter the Hadean, the age of hell. Then, everything fades into darkness. Before the scene goes away you have a glimpse of large, bright eyes looking at you. The Goddess herself is there, dancing in the emptiness of space while she creates the world. Gaia, the mother of us all.

_______________________________________________________________________

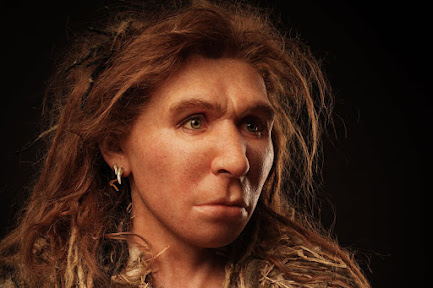

Some images. None of them refers to a specific description in the text of this post, but they can give us some idea of what our ancestresses may have been looking like.

This woman lived in Tuscany probably during the 2nd century BC, more than 2000 years ago. We know her name, "Larthia Seianti." She was Etruscan, a rich woman (note the armilla bracelet on her arm) who could afford an elaborate sculpture over her sarcophagus. It is a realistic portrait, at least in part. And, curiously, she looks a lot like a Tuscan friend of mine, living in Tuscany nowadays. She is likely one of her ancestress, just as an ancestress of mine.

The reconstruction of the face of a Neolithic woman who lived about 7,500 years ago in the area that is now called Gibraltar. She has been nicknamed "Calpeia" from the ancient name of the Gibraltar mountain, "Mons Calpe." DNA analysis shows that she, or her immediate ancestors, came to the Iberian peninsula most likely from Anatolia by boat. (source)

The "Venus of Brassenpouy," discovered in 1894 in Southern France. It is a portrait of someone who lived more than 20,000 years ago. We cannot say whether it is realistic or not, just as we cannot be completely sure that it is a woman's face. But it is perhaps the earliest recongizabòe portrait ever made in human history.

An impression of how a Paleolithic woman could have looked like, living maybe 20,000-50,000 years ago in Europe. Note her dark skin: it is a remnant of her African ancestry. (source)

A reconstruction of the face of a Neanderthal woman (from Earth Archives). She might have lived a few hundred thousand years ago. Several things in this image are uncertain, but note her heavy brow ridges, a typical Neanderthal characteristic. Note her eyes and her skin: the light color is a characteristic of people living in Northern regions. Is she an ancestor of some of us? It is not completely certain but, yes, many of us have Neanderthal genes in their DNA.

The reconstruction of a female Australopithecus who could have been living in Africa some 2 million years ago. If she had the typical human metabolism, she must have been capable of cooling by sweating, a feature incompatible with a thick body hair. And, indeed, she is shown with sparse body hair, although she may well have had none. Note also her human-like round breasts. It is a likely secondary sexual characteristics of hominins which tend to stand upright most of the time. She probably also had round buttocks, as modern women do. An ancestress of ours? Maybe. (source)

Underwater vents, somewhere at the bottom of the ocean. It is commonly believed that life on Earth started in this kind of environment, some 3-4 billion years ago. Can you see the Goddess Gaia dancing in there? Maybe. (source)