You, Reginald, three times traitor you: Traitor to me as my temporal vassal, Traitor to me as your spiritual lord, Traitor to God in desecrating His Church. (T.S. Eliot, "Murder in the Cathedral")

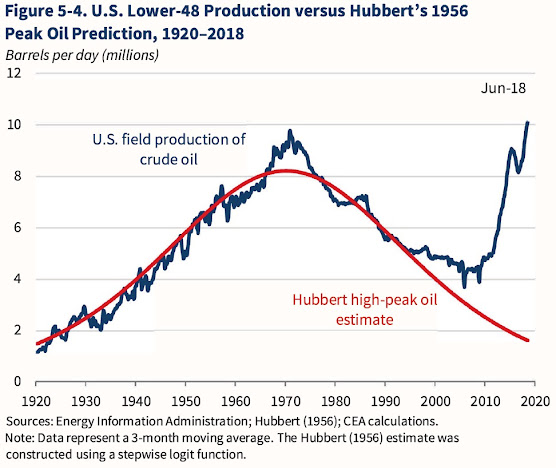

About ten years ago, my friend and colleague Massimo Nicolazzi wrote that the inversion of the declining trend of oil production in the US could not be neglected any longer. I commented by saying that it was a short-lived flare that couldn't last for long.

It turned out that Nicolazzi was right and I was wrong. By now, the growth of the US oil production curve has been lasting for more than ten years and is still ongoing -- it was not just a short-lived flare. Of course, it cannot last forever but, for the time being, it changed everything. For instance, it propelled the American Empire back to the path of world domination that the Neocons theorized in the 1990s.

Does that mean that Hubbert's "peak oil" theory is wrong and must be discarded? Of course not. It only means reinforcing some of the basic rules of complex systems. For instance, the one that goes, "complex systems always surprise you," and also, "never take an example as a rule."

So, when dealing with collapse (that I call the "Seneca Cliff), we should always remember that collapse is not an event; it is a process. Collapses have a history, they are the result of the interaction of several factors, and the same processes that generate collapse can also generate its opposite, which I tend to call the "Seneca Rebound." It is normal. There is nothing definitive in the universe, and collapses exist because the old must leave space for the new.

Recently, for another unexpected change, I identified a new trend: the rapid growth of renewable energy production worldwide. A trend that can be well described by some recent studies in terms of the EROI (energy returned for energy invested) of renewables having become several times larger than that of fossil fuels. No wonder we are seeing -- or we'll soon see -- a revolving door effect in energy production. Fossils are out, and renewables are in. History rhymes, as it usually does!

Then, just like Nicolazzi's statement about tight oil was hated by peak-oil hardliners (including me), my statements on renewables were understood as a mortal offense by catastrophistic hardliners. You can't believe how nasty their comments have been: apart from branding me an incompetent, an idiot, and ignorant of the basic laws of physics, catastrophism seems to be strictly linked to conspirationism, so people have been writing that I cannot tell the truth because I am blackmailed by the powers that be (no, really, someone wrote exactly that!).

The problem is the science of complex systems is never black or white. It doesn't allow for absolute truths, nor is it sympathetic to people choosing between complacency and panic (the two functioning modes of human beings according to James Schlesinger). The science of complex systems is, well, complex, and it needs a little mental flexibility to be understood. Not that it takes superhuman mental capabilities, not at all. It is just that you need to free yourself from the schematic way of reasoning that's normally imposed on all of us by the media.

I tried to explain these points in my book "Before Collapse" -- which has been recently translated into Spanish. Jorge Riechmann wrote a preface to the Spanish edition where he does an excellent job of summarizing the main points of the book. He calls me "a very optimistic collapsologist," which may be a good definition as long as you understand that it does not mean that collapses do not exist. They do. It is just that we have to learn to live with them.

The preface of the Spanish version book "Before Collapse," translated into English. The English version can be found at this link.

Collapse Better (Notes about an optimistic book on collapses)

By JORGE RIECHMANN

(Published as an introduction to Ugo Bardi's book Antes del colapso, published by Los libros de la catarata in 2022).

1 At the height of the June 2022 heat wave, French anthropologist Sylvain Perdigon recalled how in 2014 a French TV "weatherwoman" presented the hypothetical weather forecast for August 18, 2050 as part of a campaign to alert about the reality of climate change. Now her forecast of extreme temperatures for that distant day had become the actual forecast for mid-June 2022.[1] The weather forecast for 2050 is now the real one.

As far as the ecosocial crisis and climate tragedy are concerned, everything is systematically going systematically worse than expected, as Ferran Puig Vilar often reminds us. For example, the damage that climatologists expected to become visible in the middle of the 21st century is already here with us. "Humanity seems to be bent on playing a deadly game of Russian roulette where the Earth's climate is a loaded weapon," writes Professor Ugo Bardi in this book.

2 We are living an end of the world. Not the end of the world: Mother Earth will still be there. The basic levels of life on Gaia[2] - bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae, lichens, and many kinds of plants - are extraordinarily resilient. But the world as we have known it - the familiar and easily habitable Earth of the Holocene - is unraveling before our eyes; and the desperate efforts of many people to cling to that familiar - and now entirely unrecoverable - normality do not alleviate our situation, but rather aggravate it.

It is not the end of the world - it is not the death of Gaia, it is not the end of life on planet Earth - but it is the end of our world. What does one do in such a situation?

3. For example, read Ugo Bardi. People close to Libros de la Catarata already know the Florentine professor: it was an excellent idea to translate and publish in 2014 his book The Limits to Growth revisited, a thorough and clear-sighted analysis of that very important 1972 book, The Limits to Growth, the first of the reports to the Club of Rome. Now that it is fifty years since the publication of that pioneering work (using the modeling of the world system thanks to system dynamics), which allowed us to understand the tendency to overshoot followed by collapse that characterizes industrial societies, it is a good time to recover that first book by Bardi in Spanish - and it would be an excellent accompaniment to the one you now hold in your hands, dear reader, curious reader.[3][4] The Limits to Growth Revisited, the first book by Bardi in Spanish, is an excellent accompaniment to the one you are now holding in your hands.

4. Ugo Bardi, theorist of complex systems (those systems that exhibit strong feedback effects, he defines at a certain point in this book),[4] has been reflecting for more than a decade on the "Seneca effect" starting from a first intuition in 2011;[5] in the spring of 2017 he published The Seneca Effect: Why Growth is Slow but Collapse is Rapid (Springer, 2017); then, in 2020, Before the Collapse, this second book on the Seneca effect that is now translated into Spanish. If one had to call someone a collapsologist in the proper sense, for his commitment to an understanding as objective and rational as possible of this kind of phenomena, it would be Professor Bardi, from the Department of Chemistry at the University of Florence.

The strong interconnection between the subsystems of a complex system can lead, as a result of the impact of a perturbation on one or some of these nodes or subsystems, to the collapse of the entire network. Thus, the development of complex systems often responds to what Professor Bardi calls the Seneca mode: it is an asymmetrical process, where growth is slow and decline is very marked. Catastrophe comes much sooner than our intuition would expect and tends to catch us unawares.

You will also be dealing, in these pages, with Seneca's precipices, Seneca's bottlenecks, and Seneca's rebounds: the Cordovan philosopher gives a lot of play in the hands of the Florentine physical-chemist.

5. If in a book the word overshoot appears already in the preface, as it does here, we have an indication that it is probably going to talk about essential things.

And speaking of ecological overshoot followed by collapse, I would like to point out here what seems to me to be an internal contradiction between the explanations proposed by our author. At one point he argues that "if the American elites have decided that there is no hope of saving the whole world, the logical thing to do is to go into 'deception mode' and let most people die": that is why Donald Trump and the Republican Party are climate deniers. It is not that they ignore the reality of basic biophysical facts, but that they accept a large-scale genocide from which the elites will be spared. At a later point, however, the Florentine professor suggests otherwise: "No one seems to understand that the problem, today, is not one of expanding their country's borders, but of ensuring the physical survival of their citizens in the face of potentially disastrous events related to climate change and ecosystem collapse." So where does that leave us: ignorant elites or genocidal elites?

6. Bardi insists many times that "collapse is not a mistake, it is a characteristic feature" of complex systems in the Universe we inhabit (p. 40). While we cannot avoid many collapses (and every complex system will collapse, given enough time), we can at least try to prepare for them and collapse better. Before the Collapse (a title that suggests a double meaning: before the collapse, yes, but also facing the collapse) is a good guide for that journey, and the frequent touches of humor with which the author de-dramatizes his subject of study, in itself - it is not necessary to insist on it - very dramatic, are appreciated. Along with humor, the broad contextualization (ultimately in a cosmic and Big History context) is another resource that helps to de-dramatize.

7. Something very appealing about Professor Bardi is his interdisciplinary appetite. An appetite that finally takes shape in a very broad culture, not only on chemistry and physics matters but also on humanistic subjects (with special emphasis on history): his work offers many materials for that Third Culture (building bridges between natural sciences, social sciences and humanities) that Francisco Fernández Buey was asking us for.[6][7].

8. Collapse is not a failure of complex systems, insists the Florentine professor, but a feature of their mode of functioning: the Universe is like that. Would this be a pessimistic position? But pessimism is forbidden in our ranks! If one does not manifest at least a sufficiently muscular optimism of the will, one risks severe reprimands.

Well: against the compulsory optimism to which so many prescribers would like to subject us left and right (because pessimism, it is often said, demobilizes and works as a self-fulfilling prophecy), Bardi's rational effort to understand the dynamics of collapse is very much to be welcomed. (I confess that, having disastrously exhausted the cycle of emancipatory mobilization of 15-M movement (the Spanish "indignados", the "outraged"), hearing the adjective "illusionary" in contexts of political debate makes my guts churn rather than lift my spirits). And for those who prefer not to think of any kind of collapse without sanctifying themselves, you already have the energetic and counter-apocalyptic Rosi Braidotti, or the more proximate Zamora Bonilla.[7]

9. Bardi is a very optimistic collapsologist. Anyone who has followed his involvement in the debates on energy transitions over the last decade knows this. This optimism manifests itself for example in an article such as "The Sower's way: a strategy to attain the energy transition",[8] his particular Parable of the Sower also evoked in this book, full of confidence in the technical possibility of a smooth transition to renewable energy sources. However, his socio-political realism leads him to temper this technological optimism: such a transition would be possible, yes, but it is extremely improbable judging by the political course our societies are following.

The CIA director and US Defense Secretary James Schlesinger is credited with an observation that Bardi takes up several times in this book: human beings would have only two modes of operation, complacency and panic. To disprove him, it would be necessary that our processes of reflection and deliberation allow us to truly prepare ourselves (on a socially significant scale) for a future whose configuration we will never know, but whose structure of ecosocial collapse is today very discernible. The entire effort deployed in this work is intended to provide us with intellectual tools for that task.

10. Along with the story of the Roman Empress Galla Placidia, Japan in the Edo period is a second great positive historical example from which we can learn in thinking about transitions to sustainability. "What the story of Edo Japan tells us matches what we know about complex systems: they tend toward stability. In other words, our current fixation on growth may just be a quirk of history destined to disappear in the future when we are forced to live within the limits of the Earth's ecosystem." However, warns Bardi in 2020 in words that take on a somber resonance in 2022, "there is one condition we urgently need for this: peace, as the Edo experience tells us." Far from progressing a pacification of international relations that would allow us to cope with the processes of ecosocial collapse underway, on February 24, 2022 the invasion of Ukraine by Russia accelerated a generalized militarization that precipitates us in the opposite direction to where we would need to move.

In these fateful times, El País editorializes with exaltation about the European Union as a "new geopolitical power" (March 1, 2022). David Rieff, on the next page, also stresses that "Europe is entering a new era of hard power". Where we would need gaia-politics and an unprecedented level of international cooperation, the old geopolitics of destructive competition between nation-states and the blocs they are shaping is deepening: a world of "Combatant Empires" (Rafael Poch de Feliu) [9] And the general framework is an ecocide that includes in its bosom all kinds of promises of genocide.

The already very bad world we had is being transformed, before our wide-open eyes, into a much worse one. "It should never have come to this" could be the answer to almost everything that is happening to us. But we are already there, and from there it is up to us to act now... Recalling, for example, these verses by Brecht:[10]

When the war begins/ your brothers may be transformed/ and their faces may no longer be recognizable/ but you must remain the same/ they will go to war, not/ as to butchery, but/ as serious work. Everything/ they will have forgotten. But you/ must not forget anything.// They'll pour firewater down your gullet/ like the others. But you/ must remain sober.

11. Bearing in mind all the play that the so-called Spanish "senequismo" has given in the history of ideas in our country (with outstanding contributions such as those of Ángel Ganivet or María Zambrano), and how at times the Roman Stoic philosopher born in Cordoba has come to embody the sage par excellence in the Spanish popular imagination (in such a way that the expression "he is a Seneca" is used to praise the wisdom of someone), it is not bad that the common thread of Bardi's reflection is precisely a thought of the Cordovan philosopher. Namely, what Seneca said about collapse in one of his letters to Lucilius: "It would be a consolation for our weakness if things could be restored as soon as they are destroyed; but the opposite is true: growth is slow, but ruin is swift."[11] We will decline, but we could collapse.

We will collapse, but we could collapse better. Bardi outlines a Seneca strategy that can help us in this: accept that change is necessary and that, in many cases, opposing it leads to a more rapid collapse. Accepting the inevitable will allow us to better prepare ourselves to collapse (and perhaps even avoid collapse): "Seneca's strategy is not to oppose the tendency of the system to go in a certain direction, but to steer it in such a way that collapse does not have to occur. The key to the strategy is to prevent the system from accumulating so much tension that it is then forced to discharge it abruptly." Towards the end of the book, a notion of eco-stoicism is suggested,[12] just before recalling the stimulating and novel story of Galla Placidia, the last Roman empress.

12. Seneca also wrote: "Live each day as if one day were your whole life". Not bad advice for times as difficult as ours. Of Bardi we can also say: this guy is a Seneca!

Notes

[1] Tweet of June 15, 2022: https://twitter.com/sylvaindarwish/status/1537181101357256704

[2] It is worth remembering here that Ugo Bardi is one of the scientific defenders of the Gaia theory: see for example his essay "Gaia exists! Here is the proof" on the blog Cassandra's Legacy, 4 August 2019; https://cassandralegacy.blogspot.com/2019/08/gaia-exists-here-is-proof.html . For his idea of Gaia as a holobiont, see for example https://cassandralegacy.blogspot.com/2020/06/gaia-is-one-of-us-onward-fellow.html

Bardi, whose intellectual effervescence cheers us up and sometimes overwhelms us a bit, recently started a new and stimulating blog on the Proud Holobionts (see e.g. https://theproudholobionts.blogspot.com/2022/06/survival-of-fittest-or-non-survival-of.html ). The introductory text of that blog reads:

We are all holobionts: groups of organisms that help each other. As humans, we could not survive without the microorganisms that populate our bodies. But all living creatures on Earth are holobionts, and the ecosystem itself is a giant holobiont (which some call 'Gaia'). The holobiont concept can also be used for real and virtual non-biotic structures, enterprises, states, ideas, and ideologies, as well as the behavior of ideas ('memes') on the World Wide Web. The term holobiont was pioneered by Lynn Margulis in 1991. She was also co-developer of the Gaia concept.

[3] Bardi recalls part of his analysis of The Limits to Growth in the first chapter of this book, "The Science of Doom: Shaping the Future".

Allow me a small digression. The denialism of biophysical limits that prevails in the dominant culture can be well studied through two exemplary cases: what may be called the "Georgescu Roegen affair" and then "The Limits to Growth affair" in the 1970s (regarding the former, see our book Bioeconomics for the 21st Century. Actualidad de Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, edited by José Manuel Naredo, Luis Arenas and Jorge Riechmann in Catarata, Madrid 2022). And then, from the 1990s onwards, the refusal to confront global warming, which is spectacularly illustrated by the "Nordhaus case", is impressive. William Nordhaus, one of the most belligerent economists against The Limits to Growth from 1972, was awarded the so-called "Nobel Prize" for economics in 2018. In his acceptance speech in Stockholm, this neoclassical economist suggested that the "optimal policy" to address climate change would result in "acceptable global warming" of about 3°C by 2100 and 4°C by 2150! Climatologists (and scientists from other disciplines), unlike neoclassical economists (who unfortunately have come to dominate their discipline, cancelling out rivals who advocated more reasonable economic theories), believe that global warming of this magnitude would be catastrophic (probably incompatible with the mere survival of the human species). This is the madness of the BAU (Bisnes Comodecustom)...

[4] "A system is complex if, and only if, it exhibits strong feedback effects. Every day we are confronted with complex systems: animals, people, organizations, etc. It is not difficult to understand what is complex and what is not: it depends on whether the reaction to external perturbations is dominated by feedback or not. Think of a rock compared to a cat..."

[5] See his blog https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/

[6] Francisco Fernández Buey, Para la Tercera Cultura (edited by Salvador López Arnal and Jordi Mir), El Viejo Topo, Barcelona 2013.

[7] Good commentary in Asier Arias, "¿Quién son los contra-apocalípticos?", in the handcrafted compilation of texts in the digital magazine 15/1515 issue -8 ½, Spring 2022, p. 69-77. Also at https://www.15-15-15.org/webzine/2021/09/11/quienes-son-los-contra-apocalipticos/

[8] Ugo Bardi, Ilaria Perissi, Denes Csala and Sgouris Sgouridis: "The Sower's way: a strategy to attain the energy transition", International Journal of Heat and Technology vol. 34, Special Issue 2, October 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.18280/ijht.34S211 ; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316337020_The_Sower's_way_to_strategy_to_attain_the_energy_transition.

[9] See for example Rafael Poch, "Lo que nos van explicando sobre la guerra," ctxt, May 1, 2022; https://ctxt.es/es/20220501/Firmas/39740/Rafael-Poch-Rusia-Putin-ucrania-guerra-origen-otan-europa-estados-unidos-imperios-combatientes-consecuencias.htm

[10] Bertolt Brecht, Más de cien poemas. Hiperión, Madrid 2005, p. 211.

[11] I give the translation of Francisco Navarro, Epístolas morales de Séneca, Madrid 1884, p. 370.

[12] We could speak of a Taoist eco-stoicism that is articulated in considerations like this: "Like all human beings, the Stoics had their limits, but I believe that Seneca and others like Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius understood a fundamental point that most of their contemporaries forgot, just as we often forget. It is that complex systems are best handled by 'going with the flow' rather than trying to force them into the shape we want. This can actually make things worse, as another modern-day philosopher, Jay Forrester, told us when he talked about 'pushing the levers in the wrong direction'."

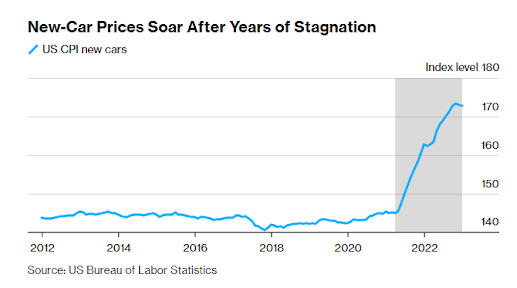

This is an amazing graph, one of a series illustrating the several rapid changes we are experiencing nowadays. It shows the reversal of a trend that saw cars becoming more and more affordable over the past 50 years or so. But now, the market is rapidly changing. Prices are soaring, and even used cars are becoming more expensive and difficult to find. Not only are car prices rising, but also those of fuel (especially diesel fuel), maintenance, and insurance. Add to that how governments keep harassing car owners, seen as cash cows to be milked by taxes and traffic sanctions. The results are obvious: A lot of people can't afford cars anymore, Car sales have been declining for several years, but the trend is accelerating, and it will likely accelerate even more in the future (data from Statista).

This is an amazing graph, one of a series illustrating the several rapid changes we are experiencing nowadays. It shows the reversal of a trend that saw cars becoming more and more affordable over the past 50 years or so. But now, the market is rapidly changing. Prices are soaring, and even used cars are becoming more expensive and difficult to find. Not only are car prices rising, but also those of fuel (especially diesel fuel), maintenance, and insurance. Add to that how governments keep harassing car owners, seen as cash cows to be milked by taxes and traffic sanctions. The results are obvious: A lot of people can't afford cars anymore, Car sales have been declining for several years, but the trend is accelerating, and it will likely accelerate even more in the future (data from Statista).