A "meme" is a small unit of information that can easily move from one human mind to another. It is the virtual equivalent of a virus in the sense that it "infects" people and influences their behavior. To explain the concept, maybe the best way is with an example: how my grandmother was absolutely convinced that nobody ever should drink a glass of milk without having boiled it first. She was infected with a meme that we could describe as "boil the damn milk." It was simple and direct, but, unfortunately, completely useless in the 1960s, when pasteurization had become common.

My grandmother was not stupid: she was simply applying a tested method to deal with things she knew little about. The problem is that memes can be (or become) wrong or harmful, and yet they are very difficult to dislodge. In the photo, you see Colin Powell, in 2003, showing a vial of baby powder while claiming that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed largely on the basis of a meme that turned out to be completely false.

My grandmother was not stupid: she was simply applying a tested method to deal with things she knew little about. The problem is that memes can be (or become) wrong or harmful, and yet they are very difficult to dislodge. In the photo, you see Colin Powell, in 2003, showing a vial of baby powder while claiming that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed largely on the basis of a meme that turned out to be completely false.

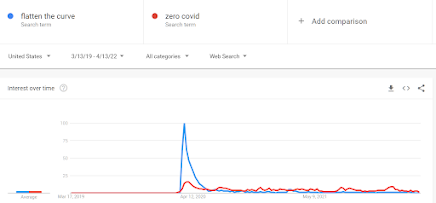

The Covid pandemic is another case of a complex story that most people are unprepared to understand. We should be trained in microbiology, medicine, epidemiology, and more -- no way! So, we rely on simplified snippets to guide our everyday activities. "Wear the damn mask," "stay home," "don't kill granny," "flatten the curve," and the like. That includes our leaders, and even many of the so-called "experts".

But how can we tell whether a meme is good or bad? One way to decide is to look at its origin. All memes have a story. Sometimes they begin as sensible precautions ("boil the milk before drinking it") but, in some cases ("lock everybody inside their homes"), they have a more complicated story. Where does the lockdown meme come from? Its origin can be found in the evolution of the concept of "biological warfare." But let's go in order.

The Militarization of Biotechnologies

Biological weapons have been around for a long time in history. Ancient writers tell us of cadavers of infected people shot into besieged cities using catapults. It must have been spectacular, but it doesn't seem to have been common or especially effective. The problem with biological weapons is similar to that with chemical weapons. They are difficult to direct against specific targets and always carry the risk of backfiring. So, in modern times, bioweapons were never used on a large scale and, in 1972, a convention was enacted that outlawed biological warfare. That seemed to be the end of the story. But things were to change.

You see in Google Ngrams how the interest in biological weapons started to grow from the 1980s, onward.

The Ngrams results are confirmed by an examination of the scientific literature, as you may see by using Google Scholar or the Web of Science. The figure shows the number of papers dedicated to biological weapons (note that in the figure years go right to left in the graph and that the 2022 data are still incomplete.)

The origin of this renewed interest lies in the development of modern genetic manipulation technologies, supposed to be able to create new, and more deadly germs. But they can do much more than that: what if you could "tailor" a virus to the genetic code of specific ethnic groups, or even to the DNA of single persons? That remains (fortunately) for now in the realm of science fiction, but there is a simpler and more realistic approach. You can direct a virus to harm the enemy while sparing your population. You can do that if you have a vaccine, and they don't (like the old Maxim gun in colonial warfare). Considering that biological weapons are also cheap, you can see how the idea of biological warfare has become popular, with China often believed to be a leader in this field. You can read an in-depth discussion on this point on Chuck Pezeshky's site.

Before going on, stop for a moment to remember that these are just ideas: they have never been put into practice. And you are discussing lethal viruses that can kill millions (maybe hundreds of millions) of people. What could go wrong? Nevertheless, the idea of a weapon that only kills your enemies while sparing your forces is an irresistible meme for military-oriented minds. Then, once the meme is loose in the memesphere, it starts acting with a force of its own. The increasing interest in bioweapons indicates that during the past 3-4 decades, military planners started believing that "genetic warfare" was a real possibility. At this point, strategic planning for a biological war became a necessity, in particular about what should have been done to prepare a country to react when targeted with bioweapons.

The diffusion of this meme generated a revolution in the views on how to contain an epidemic. Earlier on, the generally accepted view favored a soft approach: letting the virus run in the population with the objective of reaching the natural "herd immunity". For instance, in a 2007 paper, the authors examined a possible new influence pandemic and rejected such ideas as confinement, travel bans, distancing, and others. On quarantines, they stated that "There are no historical observations or scientific studies that support the confinement by quarantine of groups of possibly infected people for extended periods in order to slow the spread of influenza."

But when the military meme of biological warfare started emerging, things changed. A bioweapon attack is nothing like a seasonal flu: it is supposed to be extremely deadly, able to cripple the functioning of an entire state. Facing such a threat, waiting for herd immunity is not enough: the virus has to be stopped fast to allow the defenders to identify the virus and develop a vaccine.

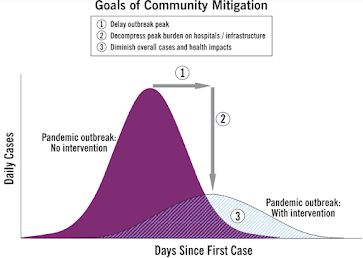

You can find several documents on the Web advocating an aggressive attitude toward epidemics. One was prepared by the Department of Homeland Security in 2006. Another comes from the Rockefeller Foundation in 2010, where you can read of a scenario called "Operation Lockstep" that described something very similar to what came to pass in 2020 in terms of restrictions. Possibly, the most interesting document in this series is the one written in 2007 for the CDC by Rajeev Venkayya. The document didn't use the term "lockdown" but it proposed a drastic series of measures to counter a possible outbreak that leading nearly two million victims in the United States only. It proposed a series of restrictions on the movement of people and, for the first time, the concept of "flattening the curve." It had a remarkable influence on the events that took place in 2020. We'll go back to this graph later.

Up to 2020, all these ideas remained purely theoretical, just memes that floated in the memesphere. Things were soon to change.

The Wuhan Lockdown meme

In early 2020, the Chinese government reported the discovery of a new virus, that they labeled SARS-Cov-2, rapidly spreading in the city of Wuhan. The authorities reacted by enacting a strict lockdown of the city and a partial one in the province of Hubei. The lockdown lasted from Jan 23 to April 8, a total of about 2 months and a half.

It was an extraordinary event that finds no equivalent in modern or ancient times. Of course, quarantines have been known for centuries, but the idea of a quarantine is to confine people who are infected or who have been in contact with infected people. A lockdown, instead, means locking down everybody in a large geographical region. It had been tried only once in modern history, when a three-day lockdown was implemented in Sierra Leone with the idea of containing an outbreak of Ebola. It had no measurable effect on the epidemic.

Many people proposed elaborate hypotheses about how the Chinese government may have been planning the pandemic in advance for strategic or political reasons. I don't see this idea as believable. Citing W.J. Astore, "People who reach the highest levels of government do so by being risk-averse. Their goal is never to screw-up in a major way. This mentality breeds cautiousness, mediocrity, and buck-passing." I think the Chinese government is not different. Governments tend to react, rather than act. They also tend to be authoritarian, and a drastic lockdown is surely something that they favor since it enhances their power.

Seen in this context, it doesn't matter if the SARS-Cov-2 virus was a natural mutation of an existing virus or, as some said, it had escaped from the biological research laboratory in Wuhan. What's important is that the Chinese authorities reacted "by the book." That is, they put into practice the recommendations that could be found, for instance, in Venkayya's CDC paper, although, of course, that doesn't mean that they actually read it. The Chinese surely had their own recommendations on preparedness that we may imagine were similar to those fashionable in the West. They may have believed that the virus was a serious threat, and they may even have suspected that it was a real biological attack. In any case, it was an occasion for the Chinese leaders to show their muscles and, perhaps, also to test their preparedness plans.

Here are the results of the first phase of the pandemic in China. We see how the number of cases moved along a typical epidemic curve that started in January 2020 and went to nearly zero after two months, and there remained for two years.

There is no doubt that the Chinese government saw this result as a success. Actually, as a huge success. Don't forget that the initial reports had described an extremely deadly virus, of the kind that could cause tens of millions of victims. In practice, the deaths attributed to the SARS-Cov-2 virus in China were about 5000. Over a population of a billion and a half, it is an infinitesimal number, and the probability for a Chinese citizen to die of (or with) Covid during 2020 was of the order of 2-3 in a million. Infinitesimal, indeed. But was it was a success of the containment policies? Or simply the result of the virus being much less deadly than it had been feared to be? Whatever the case, whoever took the decision of enacting the lockdown also took the merit for its perceived success. It was a personal triumph for China's president, Xi Jinping.

Initially, it seemed that the Covid epidemic in Europe would disappear after the first wave, thanks to the NPIs. European leaders may have been genuinely convinced of this. For instance, in November 2020, the Italian Minister of Health, Mr. Roberto Speranza, published a book titled "Why we will be healed" taking credit for the successful eradication of the epidemic in Italy. But shortly afterward the number of Covid cases in Italy restarted to grow, and Mr. Speranza hastily retired his book from bookstores and from the Web. It was as if that book had never existed. In no country in the West, the number of cases could be lowered to zero, nor the epidemic could be limited to a single cycle as it had been done in China. The comparison of two years of data for China and the US is simply dramatic:

Do you notice what scam this diagram is? This figure is not based on data, has no experimental verification, no references in past studies. It is just something that the author, Mr. Venkayya, thought was a good idea. The problem is that the diagram cannot be quantified: it shows two nice and smooth theoretical curves. But, in the real world, you would never be able to observe both curves. Think of the epidemic in Wuhan: which of the two curves describes the real-world data? You cannot say: you would have needed two Wuhans, one where the restrictions were implemented, another where they weren't. Then, you could compare.

Of course, in the real world, there are no two Wuhans, but there are 51 US states that applied different versions of the concept of "restrictions" during the pandemic. A recent study by the National Bureau of Economics Research went to examine how the different states performed and found essentially no effect of the restriction on the health of the citizens. There are other studies based that show how the effect of NPIs such as lockdowns, distancing, masks, etc., is weak, if existing at all.

That leaves open the question of why the first lockdown in Wuhan was perceived to be so effective that it was replicated all over the world. The key, here, is the term "effective." If the virus had been as deadly as it was believed to be, maybe even a biological weapon, then, yes, you could claim that the Wuhan NPI had contained it. But later experience showed that the Covid virus was not much more lethal than that of normal influenza. Some data show that it may have been endemic before the outburst of 2020, so the immune system of the Chinese may have been already equipped to cope with it. That would also explain why the 2022 wave was so much stronger: the Chinese had not exposed their immune system to viruses for nearly two years, and they had become especially vulnerable to new variants.

At this point, I can propose an interpretation for the reasons for the recent Shanghai lockdown as a good example of the power of memes. It is possible that the Chinese authorities were genuinely convinced that the Wuhan lockdown of 2020 demonstrated that restrictions work (in different terms, they remained infected with the relative meme). So, facing a new wave of the COVID virus, they reacted in the same way: with a new lockdown, convinced that they are doing their best to help Chinese citizens to overcome a real threat.

If this is true, the Chinese authorities -- and the Chinese citizens, as well -- y must have been surprised when they saw that the new Covid wave refused to be flattened, as it had seemed to be during the Wuhan lockdown. The problem, at this point, lies with the stubbornness of memes, especially in the minds of politicians. A politician, in China as everywhere else, can never admit to having been wrong. When they find that some of their actions don't lead to the expected results, they tend to double down. Of course, a larger dose of a bad remedy does not usually help, but it is the way the human mind works. We may imagine that the leaders of the inhabitants of Easter Island did the same when they increased the effort in building large statues there. Incidentally, these statues were themselves another stubborn meme infecting a population.Conclusion: a memetic cascade

Two years of the pandemic are summarized in a single graphic from "Worldometers." What you see is a series of seasonal peaks, one in the summer for the Southern Hemisphere, the other in winter for the Northern Hemisphere. There is no evidence that the various campaigns of non-pharmaceutical interventions had a significant effect. Every day in the world, some 150,000 persons die for all reasons. The graph tells us that, on the average, only about 7-8 thousand people died of (or perhaps just with) Covid every day. Even assuming that all those who died with Covid can be classified as dead from Covid (not obvious at all), more than 95% of the people who died during this period died for reasons other than the Covid.

The question that we face, then, is how was it that the world reacted with such extreme measures to a threat that, seen today, was much exaggerated. It may be still too early to understand exactly what happened, but I think it is possible to propose that it was a typical "feedback cascade" in the world's memesphere. A convergence of parallel views from politicians, decision-makers, industrial lobbies, and even simple citizens, most of them truly convinced that they were doing the right thing.

I don't mean here that there were no conspiracies in this story, in the sense of groups of people acting to exploit the pandemic for their personal economic or political interests. Lobbies and individuals do ride memes for their own advantage. So, when the pharmaceutical industry discovered that they could make money with vaccines against the Covid, they pushed hard for the meme to spread. The surveillance industry did the same. And governments, of course, pushed for more control over their citizens. They are naturally authoritarian and the Chinese government may not be especially more authoritarian than the Western ones.

But, overall, memes can be a force that moves infected people even against their personal interests. My grandmother had no advantage, just a slightly higher cost, from her habit of boiling her milk before drinking it. It is much worse for the Covid story. A lot of ordinary people fully believed the memes that the government's propaganda machine was pushing and they did things that were positively harming them, physically, socially, and economically. They still do, memes are resilient. Daniel Dennett said that "a human being is an ape infested with memes." and the Covid story shows that it is true.

Fortunately, the number of cases in China seems to have reached its peak and from now on, it can only go down. But the recent news from Shanghai is worrisome. If the Western media are to be trusted, the Chinese government is engaged in fencing apartment buildings to keep people locked inside. It may still be way too early to say that the time of the requiem for an old meme has come.

See also the work by Jeffrey Tucker, and Chuck Pezeshky.

https://www.9news.com.au/world/china-zero-covid-policy-shanghai-xi-jinping-warning-coronavirus-asia-news/372e4151-b679-4cc6-85d7-34bf0d7040e8

"Our prevention and control strategy is determined by the party's nature and mission, our policies can stand the test of history, our measures are scientific and effective," the seven-member committee said, according to government news agency Xinhua.

They have clearly realized that they made a huge mistake, but they cannot admit that and they cannot back down. The usual disaster. And, by the way, they completely confirm my interpretation that they really believed that the lockdown in Wuhan had been a success in eradicating the virus. ("our measures are scientific" -- yeah, sure.....)