In 2003, the "Anthrax scare" led many people to use duct tape to seal the windows of their homes to protect themselves from the deadly germs. It would have been a good idea if the purpose was to suffer even more than usual from indoor pollution while at the same time doing little or nothing against a hypothetical biological attack. Yet, this folly was recommended and encouraged by the national government and local ones. It was the first taste of more to come. I already mentioned this story in a previous post, but here I'll go more in-depth into the matter.

We are still reeling from three years of madness, but it seems that many of us are starting to make a serious effort to try to understand what happened to us and why. How could it be that the reaction to the Covid epidemic involved a set of "measures" of dubious effectiveness, from national lockdowns to universal masking, that had never been tried before in humankind's history?

For everything that happens, there is a reason for it to happen, and the "non-pharmaceutical interventions" (NPIs) that were adopted in 2020 have their reasons, too. Some people speak of global conspiracies and some even of evil deities, but the origin of the whole story may be more prosaic. It can be found in the development of modern genetic manipulation technologies; a new branch of science that started being noticed in the 1990s. As it normally happens, scientific advances have military consequences; genetic manipulation was not an exception.

Not that "bioweapons" are anything new. The chronicles of ancient warfare report how infected carcasses of animals were thrown inside the walls of besieged cities and other similar niceties. More recently, during the 19th century, it is reported that blankets infected with smallpox were distributed to Native Americans by British government officials. Overall, though, biological warfare never was very effective, and not even smallpox-infected blankets seem to have been able to kill a significant number of Natives. Besides, biological weapons suffer from a basic shortcoming: how can you damage your enemies only while sparing your population? Because of this problem, the history of biological warfare does not include cases where bioweapons were used on a large scale, at least so far. The low effectiveness of bioweapons is the probable reason why it was not difficult to craft an international agreement on banning their use ("BWC", biological weapon convention), ratified in 1975.

Up to recent times, bioweapons were not seen as much more dangerous than normal germs, and the generally accepted view on how to face epidemics favored a soft approach: letting the virus run in the population with the objective of reaching the natural "herd immunity." For instance, in a 2007 paper, four respected experts in epidemiology still rejected such ideas as confinement, travel bans, distancing, and others. On quarantines, they stated that "There are no historical observations or scientific studies that support the confinement by quarantine of groups of possibly infected people for extended periods in order to slow the spread of influenza." But military planners were working on the idea that bioweapons would be orders of magnitude deadlier than the seasonal flu, and that changed everything.

Genetic engineering technologies were said to be able to create new, enhanced germs, an approach known as "gain of function." Really nasty ideas could also become possible, such as "tailoring" a virus to attack only a specific ethnic group. Even without this feature, a country or a terroristic group could develop a vaccine against the germs they created and, in this way, inflict enormous damage on an enemy while protecting the country's population (or the select few of an elite aiming at global depopulation).

Fortunately, none of these ideas turned out to be feasible. Or, at least, there is no evidence that they could be put into practice. That doesn't mean they were not explored, even though research on biological weapons is prohibited by the BWC convention. Researching new germs is orders of magnitude less expensive than making nuclear weapons, and so it is also feasible for relatively poor governments. (biological warfare is said to be the weapon of the poor). Whether truly effective bioweapons can actually exist is at least doubtful, but supposing that they could exist, then it makes sense to prepare for a possible attack.

The "anthrax scare" of 2001 was the first example of what a modern terror attack using bioweapons could look like, even though it was nothing like a weapon of mass destruction, and nobody to this date can say who spread the germs using mail envelopes. Nevertheless, it was taken seriously by the authorities, and it led to the "bioterrorism act" in 2002. Shortly afterward, Iraq was accused of having been developing biological weapons of mass destruction, and you may remember how, in 2003, Colin Powell, then US secretary of state, showed on TV a vial of baby powder, saying that it could have been a biological weapon. Over the years, several government agencies became involved in planning against bioweapon attacks, and the military approach to biological warfare gradually superseded the traditional plans on how to deal with ordinary epidemics.

The idea was that a truly deadly virus attack would cripple the infrastructure of a country and cause immense damage before the germs could be stopped by a specifically developed vaccine. So, it was imperative to react swiftly and decisively with non-pharmaceutical interventions ("NPIs") or "measures" to stop the epidemic or at least slow it down. This idea was rarely expressed explicitly in public documents, but it was clearly the inspiration for several studies that examined the effects of an abnormally deadly virus. One was prepared by the Department of Homeland Security in 2006. Another one comes from the Rockefeller Foundation in 2010, where you can read of a scenario called "Operation Lockstep" that described something very similar to what came to pass in 2020 in terms of restrictions.

These military-oriented studies were mostly qualitative. They were based on typical military ideas such as color-coded emergencies, say, "red alert," "orange alert," and the like. For each color, there were a series of recommended measures, but little was said about why exactly certain colors were chosen to be coupled with certain actions. But there were also attempts to quantify the effect of NPIs. A paper on this subject was published in 2006 by the group of Neil Ferguson of the Imperial College in London, where the authors endeavored the task of disentangling the effects of different measures on the spreading of a pathogen. Factors such as home quarantines, school closures, border closings, reduced mobility, and others were examined (interestingly, the widespread use of face masks was not considered). The study didn't expend much of an effort to compare guesswork with real-world data, but it was not so bad in comparison with the harmless mumbo-jumbo that scientists normally publish. Let's say that it might have been an interesting exercise in epidemiological modeling but nothing more. The problem was that it came at a moment in which "biological warfare" was all the rage and that it may have influenced later military planning.

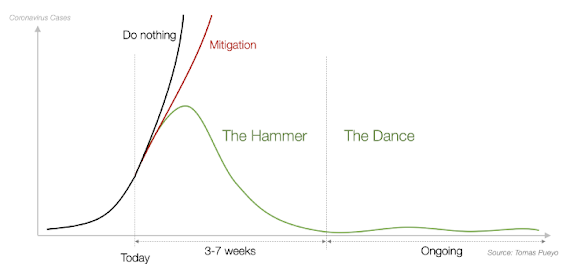

A study that had an enormous influence on the (mis)management of the 2020 pandemic was directly inspired by Ferguson's paper. It was proposed as a CDC report by Rajeev Venkayya in 2007, who presented his model in the form of the "double curve" that later became famous. Here it is; it is the origin of the "flatten the curve" meme that became popular 13 years later.

As a politician, community leader or business leader, you have the power and the responsibility to prevent this.

You might have fears today: What if I overreact? Will people laugh at me? Will they be angry at me? Will I look stupid? Won’t it be better to wait for others to take steps first? Will I hurt the economy too much?

But in 2–4 weeks, when the entire world is in lockdown, when the few precious days of social distancing you will have enabled will have saved lives, people won’t criticize you anymore: They will thank you for making the right decision.