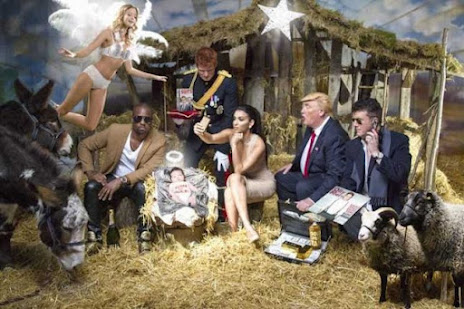

A Nativity Scene ("presepe") near Florence this year. This way of celebrating Christmas never went out of fashion in Southern Europe, and perhaps never will (but you may never know). It is part of the effort of making communication possible between people who don't speak the same language. The Catholic Church tried this method with some success, maybe we can learn something useful from this experience.

This is another non-catastrophistic post on the "Seneca Effect" blog, but don't worry. We'll return to doom and gloom next year.

The "Nativity Scene" is a traditional way to celebrate Christmas in Catholic countries, especially in Southern Europe. In Italy, it is known as the "presepe," a term that originally meant the "manger" where the baby Jesus was placed. If you have been a child in a country where this use is common, you cannot escape the fascination and the magic of these scenes. And, indeed, they make for a much more creative effort than the more recent tradition of the Christmas tree. Making a presepe may involve collecting moss from the garden to simulate the grass, making lakes using aluminum foil, creating trees with toothpicks and green-painted sponge chunks, a starry sky using blue paper with holes and, finally, the star of Bethlehem made, again, from aluminum foil.

As usual, for everything that exists, there is a reason for it to exist. And that holds also for Nativity Scenes. In the end, these scenes are forms of non-verbal communication. The fundamental point of religions such as Islam and Christianity is their universality. They accept all races, languages, regions, and cultures. That brings a problem of communication: how can an imam or a priest communicate with the faithful if they don't have a common language?

In the case of Islam, God spoke to the prophet Muhammad in Arabic, and that remains the sacred language of the faithful. Of course, modern Arabs do not easily understand the language spoken at the time of Muhammad and not all Muslims are native speakers of Arabic. But Islam focuses on the Quran, encouraging the faithful to study and understand its language. Islam is a text-based religion expressed mainly by the human voice of the mu'azzin. It sees images with diffidence,

For Christianity, the problem was much more difficult. God spoke to the prophets in Hebrew, the language of the Bible. Then, Jesus Christ spoke most likely Aramaic, whereas the Gospels were written in Greek. Then, when the center of Christianity moved to Rome, the holy texts were translated into Latin, which came to be seen as one of the main languages of Christianity. In addition, Christianity diffused rapidly into regions, such as Western Europe, which had emerged from the collapse of the Roman Empire as a hodgepodge of very different languages with different roots.

So, it made sense for the Christian Church to use visual imagery to carry the message to everybody. That was an early characteristic of Christianity, for instance, the sentence in Greek ("Iēsous Christos, Theou Yios, Sōtēr") (Jesus Christ Son of God, Savior) was turned into an acronym that could be read as "ichthys," which means "fish" and therefore could be expressed as the image of a fish. Not every Christian understood Greek, but everyone could recognize a fish.