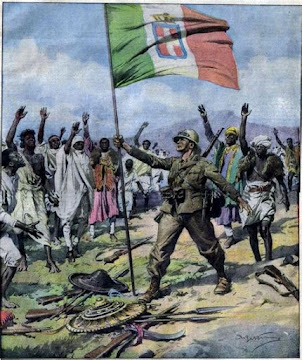

For the Orthodox Easter day of 2022, I thought to abandon the daily noise of the news and take a long-term view. So, here is a post, republished from "The Proud Holobionts," that presents the history of our planet during the past 400 million years and some hypotheses on what could happen in the next billion years or so. Easter is a time of rebirth and of hope, so let's hope for a future of peace for these poor savanna monkeys, so noisy and so unruly.

Gaia and the Savanna Monkeys.

The Great Cycle of Earth's Forests

A forest is a magnificent, structured, and functional entity where the individual elements -- trees -- work together to ensure the survival of the ensemble. Each tree pumps water and nutrients all the way to the crown by the mechanism called evapotranspiration. The condensation of the evaporated water triggers the phenomenon called the "biotic pump" that benefits all the trees by pumping water from the sea. Each tree cycles down the carbohydrates it manufactures using photosynthesis to its mycorrhizal space, the underground system of roots and fungi that extracts mineral nutrients for the tree. The whole "rhizosphere" -- the root space -- forms a giant brain-like network that connects the trees to each other, sometimes termed "the Wood Wide Web." It is an optimized environment where almost everything is recycled. We can see it as similar to the concept of "just in time manufacturing" in the human economy.

Forests are wonderful biological machines, but they are also easily destroyed by fires and attacks by parasites. And forests have a competitor: grass, a plant that tends to replace them whenever it has a chance to. Areas called savannas are mainly grass, although they host some trees. But they don't have a closed canopy, they don't evapotranspirate so much as forests, and they tend to exist in much drier climate conditions. Forests and grasslands are engaged in a struggle that may have started about 150 million years ago when grass appeared for the first time. During the past few million years, grasses seem to have gained an edge in the competition, in large part exploiting their higher efficiency in photosynthesis (the "C4" pathway) in a system where plants are starved for CO2.

Another competitor of forests is a primate that left its ancestral forest home just a couple of million years ago to become a savanna dweller -- we may call it the "savanna monkey," although it is also known as "Homo," or "Homo sapiens." These monkeys are clever creatures that seem to be engaged mainly in razing forests to the ground. Yet, in the long run, they may be doing forests a favor by returning the atmospheric CO2 concentration to values more congenial to the old "C3" photosynthetic mechanism still used by trees.

Seen along the eons, we have an extremely complex and fascinating story. If forests have dominated Earth's landscape for hundreds of millions of years, one day they may disappear as Gaia gets old. In this post, I am describing this story from a "systemic" viewpoint -- that is, emphasizing the interactions of the elements of the system in a long-term view (it is called also "deep time"). The post is written in a light mood, as I hope to be able to convey the fascination of the story also to people who are not scientists. I tried to do my best to interpret the current knowledge, I apologize in advance for the unavoidable omissions and mistakes in such a complex matter, and I hope you'll enjoy this post.

The Origin of Forests: 400 million years ago

Life on Earth may be almost 4 billion years old but, since we are multicellular animals, we pay special attention to multicellular life. So, we tend to focus on the Cambrian period (542-488 million years ago), when multicellular creatures became common. But that spectacular explosion of life was all about marine animals. Vascular plants started colonizing the land only during the period that followed the Cambrian, the Ordovician, (485 - 443 million years ago).

To be sure, the Ordovician flora on land was far from impressive. As far as we know, it was formed mainly by moss and lichens, although lichens may be much older and precede the Cambrian. Algae may have eked a precarious life on rocks even much earlier. Mosses, just like lichens, are humble plants: they are not vascularized, they don't grow tall, and they surely can't compare with trees. Nevertheless, they could change the planetary albedo and perhaps contribute to the fertilization of the marine biota -- something that may be related to the spectacular ice ages of the Ordovician. It is a characteristic of the Earth system that the temperature of the atmosphere is related to the abundance of life. More life draws down atmospheric CO2, and that cools the planet. The Ordovician saw one of these periodic episodes of cooling with the start of the colonization of the land. (image from Wikipedia)There followed another long period called the "Silurian" (444 – 419 My ago) when plants kept evolving but still remained of the size of small shrubs at most. Then, during the Devonian (419 -359 million years ago) we have evidence of the existence of wood. And not only that, the fossil record shows the kind of channels called "Xylem" that connect the roots to the leaves in a tree. These plants were already tall and had a crown, a trunk, and roots. By the following geological period, the Carboniferous (359 - 299 My ago), forests seem to have been widespread.

If we could walk in one of those ancient forests, we would find the place familiar, but also a little dreary. No birds and not even flying insects, they evolved only tens of million years later. No tree-climbing animals: no monkeys, no squirrels, nothing like that. Even in terms of herbivores, we have no evidence of the kind of creatures we are used to, nowadays. Grass didn't exist, so herbivores may have subsisted on decaying plant matter, or perhaps on ferns. Lots of greenery but no flowers, they had not evolved yet. You see in the image (source) an impression of what an ancient forest of Cladoxylopsida could have looked like during the Paleozoic era.

If we could walk in one of those ancient forests, we would find the place familiar, but also a little dreary. No birds and not even flying insects, they evolved only tens of million years later. No tree-climbing animals: no monkeys, no squirrels, nothing like that. Even in terms of herbivores, we have no evidence of the kind of creatures we are used to, nowadays. Grass didn't exist, so herbivores may have subsisted on decaying plant matter, or perhaps on ferns. Lots of greenery but no flowers, they had not evolved yet. You see in the image (source) an impression of what an ancient forest of Cladoxylopsida could have looked like during the Paleozoic era.Image Source. The "fire window" is the region of concentrations in atmospheric oxygen in which fires can occur. Note how during the Paleozoic, the concentration could be considerably larger than it is now. Fireworks aplenty, probably. Note also how there exist traces of fires even before the development of full-fledge trees, in the Devonian. Wood didn't exist at that time, but the concentration of oxygen may have been high enough to set dry organic matter on fire.

Wildfires are a classic case of a self-regulating system. The oxygen stock in the atmosphere is replenished by plant photosynthesis but is removed by burning wood. So, fires tend to reduce the oxygen concentration and that makes fires more difficult. But the story is more complicated than that. Fires also tend to create "recalcitrant" carbon compounds, charcoal for instance, that are not recycled by the biosphere and tend to remain buried for long times -- almost forever. So, over very long periods, fires tend to increase the oxygen concentration in the atmosphere by removing CO2 from it. The conclusion is that fires both decrease and increase the oxygen concentration. How about that for a taste of how complicated the biosphere processes are?

The Mesozoic: Forests and Dinosaurs

At the end of the Paleozoic, some 252 million years ago, there came the great destruction. A gigantic volcanic eruption of the kind we call "large igneous province" (sometimes affectionately "LIP") took place in the region we call Siberia today. It was huge beyond imagination: think of an area as large as modern Europe becoming a lake of molten lava. (image source)

It spewed enormous amounts of carbon into the atmosphere in the form of greenhouse gases. That warmed the planet, so much that it almost sterilized the biosphere. It was not the first, but it was the largest mass extinction of the Phanerozoic age. Gaia is normally busy keeping Earth's climate stable, but sometimes she seems to be sleeping at the wheel -- or maybe she gets drunk or stoned. The result is one of these disasters.

Yet, the ecosystem survived the great extinction and rebounded. It was now the turn of the Mesozoic era, with forests re-colonizing the land. Over time, the angiosperms ("flowering plants") become dominant over the earlier conifers. With flowers, forests may have been much noisier than before, with bees and all kinds of insects. Avian dinosaurs also appeared. They seem to have been living mostly on trees, just like modern birds.

For a long period during the Mesozoic, the landscape must have been mainly forested. No evidence of grass being common, although smaller plants, ferns, for instance, were abundant. Nevertheless, the great evolution machine kept moving. During the Jurassic, a new kind of mycorrhiza system evolved, the "Ectomycorrhizae" which allowed better control of the mineral nutrients in the rhizosphere, avoiding losses when the plants were not active. This mechanism was typical of conifers that could colonize cold regions of the supercontinent of the time, the "Pangea."

A much better representation of long-necked dinosaurs came with the first episode of the "Jurassic Park" (1993) movie series, when a gigantic diplodocus eats leaves. At some moment, the beast rises on its hind legs, using the tail as further support.

If you are a dinosaur lover (and you probably are if you are reading this post) seeing this scene must have been a special moment in your life. And, after having seen it maybe a hundred times, it still moves me. But note how the diplodocus is shown in a grassy environment with sparse trees: that's not realistic because grass didn't exist yet when the creature went extinct at the end of the Jurassic period, about 145 million years ago.

To see grass and animals specialized in eating it, we need to wait for the Cretaceous (145-66 million years ago). Evidence that some dinosaurs had started eating grass comes from the poop of long-necked dinosaurs. That's a little strange because, if you are a grazer, the last thing you need is a long neck. But new body plants rapidly evolved during the Cretaceous. The Ceratopsia were the first true grazers, also called "mega-herbivores". Heavy, four-legged beasts that lived their life keeping their head close to the ground. The Triceratopses gained a space in human fantasy as prototypical dinosaurs, and they are often shown in movies while fighting tyrannosauruses. You see that in Walt Disney's movie "Fantasia" (1940). It may have happened for real.

During the warm phase of the Cenozoic, Earth reached a maximum temperature around 55 million years ago, some 8-12 deg C higher than today. The concentration of CO2, too, was large. That is called the "early Eocene climatic optimum". It doesn't mean that this period was better than other periods in terms of climate, but it seems that Earth was mainly covered with lush forests and that the biosphere thrived.

Then, the atmosphere started cooling. It was a descent that culminated at the Eocene-Oligocene boundary, about 34 million years ago, with a new mass extinction. It was a relatively small event in comparison to other, more famous, mass extinctions, but still noticeable enough that the Swiss paleontologist Hans Georg Stehlin gave it the name of the "Grande Coupure" (the big break) in 1910. One of the victims was the brontotherium -- too bad!Unlike other cases, the extinction at the Grande Coupure was not correlated to the warming created by a LIP, but to rapid cooling. You see the "step" in temperature decline in the figure.

A typical savanna ecosystem: the Tarangire national park in Tanzania. (Image From Wikipedia). Compare with the forest image at the beginning of this post.

The savanna monkeys won the game of survival by means of a series of evolutionary innovations. They increased their body size for better defense, they developed an erect stance to have a longer field of view, they super-charged their metabolism by getting rid of their body hair and using profuse sweating for cooling, they developed complex languages to create social groups for collective defense, and they learned how to make stone tools adaptable to different situations. Finally, they developed a tool that no animal on Earth had mastered before: fire. Over a few hundred thousand years, they spread all over the world from their initial base in a small area of Central Africa. The savanna monkeys, now called "Homo sapiens," were a stunning evolutionary success. The consequences on the ecosystem were enormous.

First, the savanna monkeys exterminated most of the megafauna. The only large mammals that survived the onslaught were those living in Africa, where they had the time to adapt to the new predator as it evolved. For instance, the large ears of the African elephant are a cooling system destined to make elephants able to cope with the incredible stamina of human hunters. But in Eurasia, North America, and Australia, the arrival of the newcomers was so fast and so unexpected that most of the large animals were wiped out.

By eliminating the megaherbivores, the monkeys had, theoretically, given a hand to the competitors of grass, forests, which now had an easier time encroaching on grassland without seeing their saplings trampled. But the savanna monkeys had also taken the role of megaherbivores. They used fires with great efficiency to clear forests to make space for the game they hunted. In the book "1491" Charles Mann reports (. p 286) how "rather than domesticating animals for meat, Indians retooled ecosystems to encourage elk, deer, and bear. Constant burning of undergrowth increased the number of herbivores, the predators that fed on them, and the people who ate them both." Later, as they developed metallurgy, the monkeys were able to cut down entire forests to make space for the cultivation of the grass species that they had domesticated meanwhile: wheat, rice, maize, oath, and many others.

But the savanna monkeys were not necessarily enemies of the forests. In parallel to agriculture, they also managed entire forests as food sources. The story of the chestnut forests of North America is nearly forgotten today but, about one century ago, the forests of the region were largely formed of chestnut trees planted by Native Americans as a source of food (image source). By the start of the 20th century, the forest was devastated by the "chestnut blight," a fungal disease that came from China. It is said that some 3-4 billion chestnut trees were destroyed and, now, the chestnut forest doesn't exist anymore. The American chestnut forest is not the only example of a forest managed, or even created, by humans. Even the Amazon rainforest, sometimes considered an example of a "natural" forest, shows evidence of having been managed by the Amazonian Natives in the past as a source of food and other products.The most important action of the monkeys was their habit of burning sedimented carbon species that had been removed from the ecosphere long before. The monkeys call these carbon species "fossil fuels" and they have been going on an incredible burning bonanza using the energy stored in this ancient carbon without the need of going through the need of the slow and laborious photosynthesis process. In so doing, they raised the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere to levels that had not been seen for tens of millions of years before. That was welcome food for the trees, which are now rebounding from their former distress during the Pleistocene and reconquering the lands they had lost to grass. In the North of Eurasia, the Taiga is expanding and gradually eliminating the old mammoth steppe. Areas that today are deserts are likely to become green. We are already seeing the trend in the Sahara desert.

What the savanna monkeys could do was probably a surprise for Gaia herself, who must be now scratching her head and wondering what has happened to her beloved Earth. And what's going to happen now?

The New Large Igneous Province made by Monkeys

The giant volcanic eruptions called LIPs tend to appear with periodicities of the order of tens or hundreds of million years. But nobody can predict a LIP and, instead, the savanna monkeys engaged in the remarkable feat of creating a LIP-equivalent by burning huge amounts of organic ("fossil") carbon that had sedimented underground over tens or hundreds of millions of years of biological activity.

It is remarkable how rapid the monkey LIP (MLIP) has been. Geological LIPS typically span millions of years. The MLIP went through its cycle in a few hundreds of years. It will be over when the concentration of fossil carbon stored in the crust will become too low to self-sustain the combustion with atmospheric oxygen. Just like all fires, the great fire of fossil carbon will end when it runs out of fuel, probably in less than a century from now. Even in such a short time, the concentration of CO2 is likely to reach, and perhaps exceed, levels never seen after the Eocene, some 50 million years ago.There is always the possibility that such a high carbon concentration in the atmosphere will push Earth over the edge of stability and kill Gaia by overheating the planet. But that's not a very interesting scenario, so let's examine the possibility that the biosphere will survive the carbon pulse. What's going to happen to the ecosphere?

The savanna monkeys are likely to be the first victims of the CO2 pulse that they themselves generated. Without the fossil fuels they had come to rely on, their numbers are going to decline very rapidly. From the incredible number of 8 billion individuals, they may return to levels typical of their early savanna ancestors: maybe just a few tens of thousands. Quite possibly, they'll go extinct. In any case, they will hardly be able to keep their habit of razing down entire forests. Without monkeys engaged in the cutting business and with high concentrations of CO2, forests are advantaged over savannas, and they are likely to recolonize the land. We are going to see again a lush, forested planet where arboreal monkeys will probably survive and thrive. Nevertheless, savannas will not disappear. They are part of the ecosystem, and new megaherbivores will evolve in a few hundreds of thousands of years.

Over deep time, the great cycle of warming and cooling may restart after the monkey LIP, just as it does for geological LIPs. In a few million years, Earth may be seeing a new cooling cycle that will lead again to a Pleistocene-like series of ice ages. At that point, new savanna monkeys may evolve. They may restart their habit of exterminating the megafauna, burning forests, and building things in stone. But they won't have the same abundance of fossil fuel that the monkeys called "Homo sapiens" found when they emerged into the savannas. So, their impact on the ecosystem will be smaller, and they won't be able to create a new monkey-LIP.

And then what? In deep time, the destiny of Earth is determined by the slowly increasing solar irradiation that is going, eventually, to eliminate the oxygen from the atmosphere and sterilize the biosphere, maybe in less than a billion years from now. So, we may be seeing more cycles of warming and cooling before Earth's ecosystem collapses. At that point, there will be no more forests, no more animals, and only single-celled life may persist. It has to be. Gaia, poor lady, is doing what she can to keep the biosphere alive, but she is not all-powerful. And not immortal, either.

Nevertheless, the future is always full of surprises, and you should never underestimate how clever and resourceful Gaia is. Think of how she reacted to the CO2 starvation of the past few tens of millions of years. She came up with not just one, but two brand-new photosynthesis mechanisms designed to operate at low CO2 concentrations: the C4 mechanism typical of grasses, and another one called crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM). To say nothing about how the fungal-plant symbiosis in the rhizosphere has been evolving with new tricks and new mechanisms. You can't imagine what the old lady may concoct in her garage together with her Elf scientists (those who also work part-time for Santa Claus).

Now, what if Gaia invents something even more radical in terms of photosynthesis? One possibility would be for trees to adopt the C4 mechanism and create new forests that would be more resilient against low CO2 concentrations. But we may think of even more radical innovations. How about a light fixation pathway that doesn't just work with less CO2, but that doesn't even need CO2? That would be nearly miraculous but, remarkably, that pathway exists. And it has been developed exactly by those savanna monkeys who have been tinkering -- and mainly ruining -- the ecosphere.The new photosynthetic pathway doesn't even use carbon molecules but does the trick with solid silicon (the monkeys call it "photovoltaics"). It stores solar energy as excited electrons that can be kept for a long time in the form of reduced metals or other chemical species. The creatures using this mechanism don't need carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, don't need water, they may get along even without oxygen. What the new creatures can do is hard to imagine for us (although we may try). In any case, Gaia is a tough lady, and she may survive much longer than we may imagine, even to a sun hot enough to torch the biosphere to cinders. Forests, too, are Gaia's creatures, and she is benevolent and merciful (not always, though), so she may keep them with her for a long, long time. (and, who knows, she may even spare the Savanna Monkeys from her wrath!).

We may be savanna monkeys, but we remain awed by the majesty of forests. The image of a fantasy forest from Hayao Miyazaki's movie, "Mononoke no Hime" resonates a lot with us. But can you see the mistake in this image? What makes this forest not a real forest?

__________________________

Note: You always write what you would like to read, and that's why I wrote this post. But, of course, this is a work in progress. I am tackling a subject so vast that I can't possibly hope to be sufficiently expert in all its facets to avoid errors, omissions, and wrong interpretations. Corrections from readers who are more expert than me are welcome! I would also like to thank Anastassia Makarieva for all she taught me about the biotic pump and about forests in general, and Mihail Voytehov for his comments about the rhizosphere. Of course, all mistakes in this text here are mine, not theirs.

.jpg)