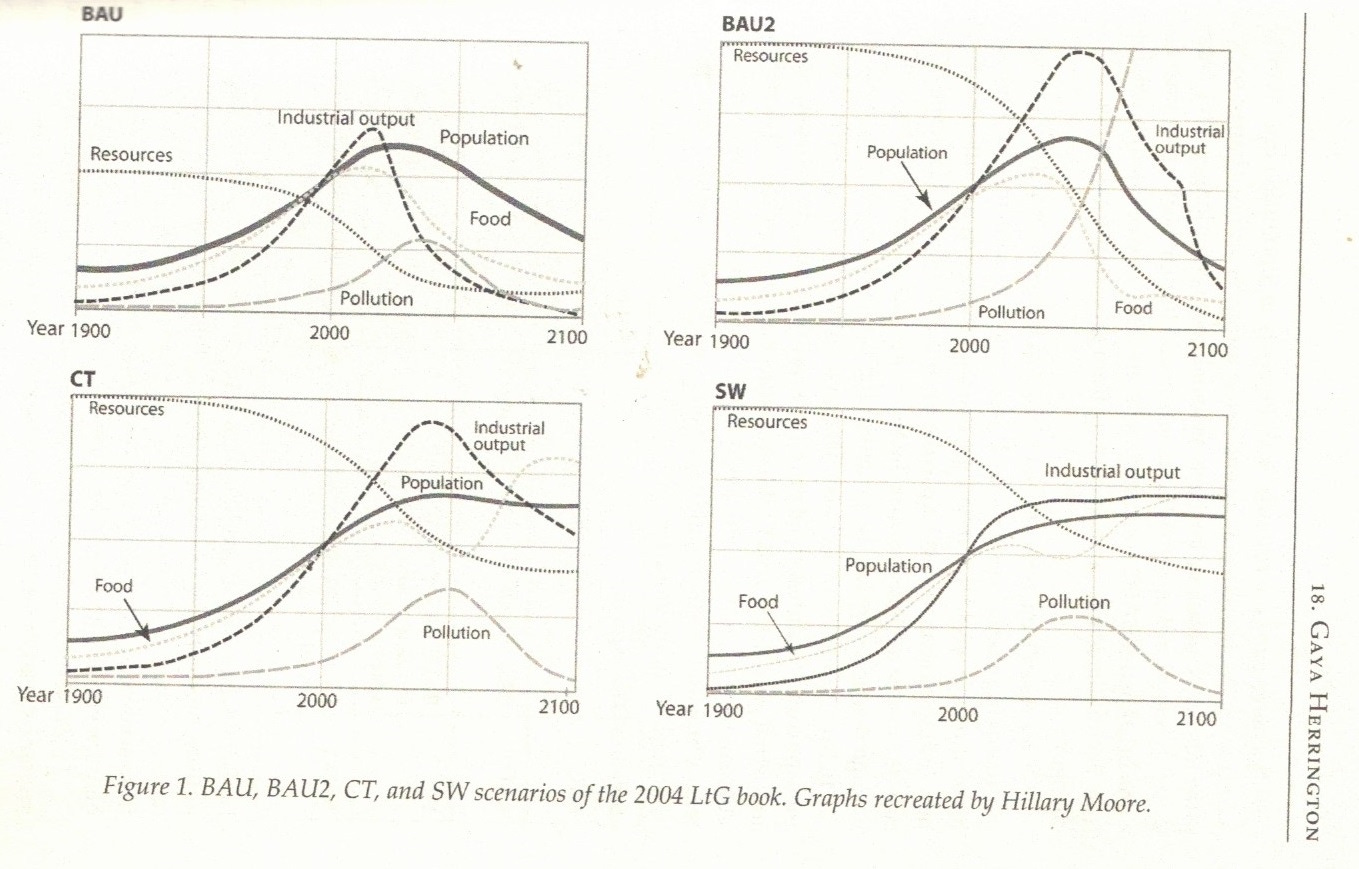

After retiring from my university, I am now involved a lot with the Club of Rome. In the photo, you see me wearing a t-shirt that reproduces the "Base Case" scenario of the 1972 report "The Limits to Growth." On the 50th anniversary of that publication, we published a new report, titled "Limits and Beyond," that summarizes the story and discussed its relevance for us and for our future.

A few months ago

I decided to retire. Actually, I ran away screaming from my university, and I never set foot again in my department afterward. And I do not plan to set foot in it again, ever.

So, how is the life of a retiree scientist? It is a dream. Freedom from bureaucracy, paperwork, research reports, grant writing, attending meetings, being part of committees, all that. I don't have to spend the 1h 30' of commuting time that I used to spend every day to go to my office and back. To say nothing about not having to torture those catatonia-suffering creatures that go under the name of "students." I feel like a retiree executioner!

More than all, I feel as if I had returned to when I was a postdoc at Berkeley, in the 1980s. At that time, I didn't have paperwork to do, no teaching, no committees, and no performance reports. I could spend 100% of my time on research. It was wonderful: I remember that the libraries of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory were open all night for researchers. And I did spend entire nights browsing the shelves. To say nothing about the bookstores in town: it was there that I discovered the concept of "peak oil."

Today, university libraries have become fortresses where you can enter only if you are fully masked and if you reserve a seat in advance. But they have become useless: the Internet gives us possibilities that we wouldn't have dreamed of in the 1980s. It is a dream if you are trained in science, if you like science, if you love science, (I still do, despite the sad state of science, nowadays).

The whole scientific knowledge of the world is at your fingertips. You can jump from paleontology to cosmology, to thermodynamics, to microbiology, or anything you fancy to learn. True, some of this knowledge is hidden behind the hideous paywalls that publishers use to make obscene profits, but I daresay that the relevant knowledge is mostly available for free. Nobody wants to publish behind a paywall anymore, except for papers they don't care much about because it is the cheap way to publish, and it gives them academic "points." But the relevant work, no, everyone wants it to be read!

That leaves a problem: how do you wade through so much information? The mass of data that you can summon onto your screen is enormous, the problem is that you risk losing yourself in a galaxy of irrelevance. In my case, I rely a lot on blogs. Blogs often provide high-quality information, sometimes truly excellent information written by scientists or by experts in their fields. Nothing like the chaotic environment of social media (to say nothing about the censorship). And nothing like the boring platitude of scientific journals.

But how do you organize your information flux from blogs? It is easy: you use a feed reader. I am always surprised at discovering how few people use feed readers to organize their information. It is simple, costs nothing, and it insures that you never miss the sources you think are relevant. And you decide what you want to read: you are not a slave to the search algorithms of whatever search engine or social media you use. I use "theoldreader.com," but there are many similar ones. Try one, your views of the world will change. You may also want to try "substack.com" -- it is the same idea: it allows you to select the subjects you are interested in. But it works only with substack blogs, whereas a generic feed reader will cover practically all the available Web sites.

There remains the problem of the sheer limits of time and the capability to absorb so much information. There is the risk to become an Internet larva, spending all the time available surfing this and that.

I am trying to cope with this problem. For one thing, I am dropping certain activities that I think are too time-consuming, and scarcely productive. For one thing, I am considering whether to resign from my position as editor at the "Biophysical Economics and Sustainability" journal. It is an interesting journal in terms of its theme, but it is still steeped in the old and obsolete scientific publishing paradigm of hiding papers behind paywalls.

Then, I think I'll drop Twitter, too. Too much noise and too little content. It is not the same for Facebook, which still allows one to present reasonably structured information -- you just have to be careful to avoid censorship, which you can do if you phrase your statements carefully. About Metaverse..... well, I still don't know what it is, but I think that you won't be able to force me into it, not even threatening me with a shotgun.

So, with all this information coming in, what is coming out? A list of what I am doing would be boring for you, but let me just tell you that I am in a burst of activities -- I don't think I've ever been so productive as a scientist as now!

Quickly, I am publishing articles in scientific journals, and I am able to publish articles that I see as relevant (and also sometimes fun. That's the way science should be, I think). Among the latest articles, one is a co-authored study on the concept of a 100% renewable-powered society (spearheaded by Christian Breyer). Another (together with Ilaria Perissi) is a re-examination of the "Mousetrap Experiment" that simulates a chain reaction, shown first in Walt Disney's movie "Our friend the atom." Another paper (still with Ilaria) is about transforming the story of "Moby Dick" into a boardgame. The reviewers seem to be a little perplexed, but I think we'll be able to publish it. And there are more papers in the pipeline.

Then, books. The main one is "Limits and Beyond," a new report to the Club of Rome that reassesses the story of the famous 1972 book, "The Limits to Growth." Then, my previous book, "The Empty Sea" (together with Ilaria Perissi), is being published in Chinese. It will appear in September. More books are in the pipeline, one is titled "The Age of Exterminations." I think that it will not be easy to find a good publisher for this one -- a little gloomy, to say the least! Anyone among readers has suggestions?

And then there are blogs and discussion groups. Let me just say that I am fascinated by the concept of "holobiont" and I am dedicating a lot of time to it. I have a blog on holobionts, that I think I will transfer soon to Substack. Right now, the way I see the concept is in terms of the "extended holobiont" synthesis. It will be published (I hope) as a chapter in a new book edited by Jean Pierre Imbrogiano and David Skribna.

The holobiont is, I think, a new paradigm that can help us frame many of the things that are causing us so much trouble nowadays. Holobionts are the building blocks of the ecosystem, and also of human-made social and economic systems. The whole idea of holobionts is to emphasize collaboration and avoid competition. Holobionts mean sharing, creating, and living. It is the way of all the creatures of the ecosystem. Gaia herself is a giant holobiont -- the master of them all! Then, of course, we are all holobionts ourselves.

And so, onward, fellow holobionts!