In 1956, Arthur C. Clarke wrote "The Forgotten Enemy," a science fiction story that dealt with the return of the ice age (image source). Surely it was not Clarke's best story, but it may have been the first written on that subject by a well-known author. Several other sci-fi authors examined the same theme, but that does not mean that, at that time, there was a scientific consensus on global cooling. It just means that a consensus on global warming was obtained only later, in the 1980s. But which mechanisms were used to obtain this consensus? And why is it that, nowadays, it seems to be impossible to attain consensus on anything? This post is a discussion on this subject that uses climate science as an example.

You may remember how, in 2017, during the Trump presidency, there briefly floated in the media the idea to stage a debate on climate change in the form of a "red team vs. blue team"

encounter between orthodox climate scientists and their opponents. Climate

scientists were horrified at the idea. They were especially appalled at the military implications of the "red vs. blue" idea that hinted at how the debate could have been organized. From the government side, then, it was quickly realized that in a fair scientific debate their side had no chances. So, the debate never took place and it is good that it didn't. Maybe those who proposed it were well intentioned (or maybe not), but in any case it would have degenerated into a fight and just created confusion.

Yet, the story of that debate that was never held hints at a point that most people understand: the need for consensus. Nothing in our world can be done without some form of consensus and the question of climate change is a good example. Climate scientists tend to claim that such a consensus exists, and they sometimes quantify it as 97% or even 100%. Their opponents claim the opposite.

In a sense, they are both right. A consensus on climate change exists among scientists, but this is not true for the general public. The polls say that a majority of people know something about climate change and agree that something is to be done about it, but that is not the same as an in-depth, informed consensus. Besides, this majority rapidly disappears as soon as it is time to do something that touches someone's wallet. The result is that, for more than 30 years, thousands of the best scientists in the world have been warning humankind of a dire threat approaching, and nothing serious has been done. Only proclaims, greenwashing, and "solutions" that

worsen the problem (the "hydrogen-based economy" is a good example).

So, consensus building is a fundamental matter. You can call it a science or see it as another way to define what others call "propaganda." Some reject the very idea as a form of "mind control," or practice it in various methods of rule-based negotiations. It is a fascinating subject that goes to the heart of our existence as human beings in a complex society.

Here, instead of tackling the issue from a general viewpoint, I'll discuss a specific example: that of "global cooling" vs. "global warming," and how a consensus was obtained that warming is the real threat. It is a dispute often said to be proof that no such a thing as consensus exists in climate science.

You surely heard the story of how, just a few decades ago, "global cooling" was the generally accepted scientific view of the future. And how those silly scientists changed their minds, switching to warming, instead. Conversely, you may also have heard that this is a myth and that there never was such a thing as a consensus that Earth was cooling.

As it is always the case, the reality is more complex than politics wants it to be. Global cooling as an early scientific consensus is one of the many legends generated by the discussion about climate change and, like most legends, it is basically false. But it has at least some links with reality. It is an interesting story that tells us a lot about how consensus is obtained in science. But we need to start from the beginning.

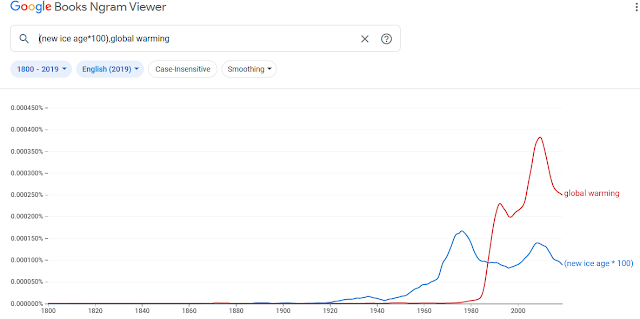

The idea that Earth's climate was not stable emerged in the mid-19th century with the discovery of the past ice ages. At that point, an obvious question was whether ice ages could return in the future. The matter remained at the level of scattered speculations until the mid 20th century, when the concept of "new ice age" appeared in the "memesphere" (the ensemble of human public memes). We can see this evolution using Google "Ngrams," a database that measures the frequency of strings of

words in a large corpus of published books (Thanks, Google!!).

You

see that the possibility of a "new ice age" entered the public consciousness already in the 1920s, then it grew and reached a peak in the early 1970s. Other strings such as "Earth cooling" and the like give similar results. Note also that the database "English Fiction" generates a

large peak for the concept of a "new ice age" at about the same time, in the 1970s. Later on, cooling was completely replaced by the concept of global warming. You can see in the figure below how the crossover arrived in the late 1980s.

Even after it started to decline, the idea of a "new ice age" remained popular and journalists loved presenting it to the public as an imminent threat. For instance, Newsweek printed an article titled "

The Cooling World" in 1975, but the concept provided good material for the catastrophic genre in fiction. As late as 2004, it was at the basis of the

movie "The Day After Tomorrow."

The Cooling World" in 1975, but the concept provided good material for the catastrophic genre in fiction. As late as 2004, it was at the basis of the

movie "The Day After Tomorrow."Does that mean that scientists ever believed that the Earth was cooling? Of course not. There was no consensus on the matter. The status of climate science until the late 1970s simply didn't allow certainties about Earth's future climate.

As an example, in 1972, the well-known report to the Club of Rome, "The Limits to Growth," noted the growing concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere, but it did not state that it would cause warming -- evidently the issue was not yet clear even for scientists engaged in global ecosystem studies. 8 years later, in 1980, the authors of "The Global 2000 Report to the President of the U.S." commissioned by president Carter, already had a much better understanding of the climate effects of greenhouse gases. Nevertheless, they did not rule out global cooling and they discussed it as a plausible scenario.

The Global 2000 Report is especially interesting because it provides some data on the opinion of climate scientists as it was in 1975. 28 experts were interviewed and asked to forecast the average world temperature for the year 2000. The result was no warming or a minimal one of about 0.1 C. In the real world, though, temperatures rose by more than 0.4 C

in 2000. Clearly, in 1980, there was not such a thing as a scientific consensus on global warming. On this point, see also the paper by Peterson (2008) which analyzes the scientific literature in the 1970s. A majority of paper was found to favor global warming, but also a significant minority arguing for no temperature changes or for global cooling.

Now we are getting to the truly interesting point of this discussion. The consensus that Earth was warming did not exist before the 1980s, but then it became the norm. How was it obtained?

There are two interpretations floating in the memesphere today. One is that scientists agreed on a global conspiracy to terrorize the public about global warming in order to obtain personal advantages. The other that scientists are cold-blooded data-analyzers and that they did as John Maynard Keynes said, "When I have new data, I change my mind."

Both are legends. The one about the scientific conspiracy is obviously ridiculous, but the second is just as silly. Scientists are human beings and data are not a gospel of truth. Data are always incomplete, affected by uncertainties, and need to be selected. Try to develop Newton's law of universal gravitation without ignoring all the data about falling feathers, paper sheets, and birds, and you'll see what I mean.

In practice, science is a fine-tuned consensus-building machine. It has evolved exactly for the purpose of smoothly absorbing new data in a gradual process that does not lead (normally) to the kind of partisan division that's typical of politics.

Science uses a procedure derived from an ancient method that, in Medieval times was called disputatio and that has its roots in the art of rhetoric of classical times. The idea is to debate issues by having champions of the different theses squaring off against each other and trying to convince an informed audience using the best arguments they can muster. The Medieval disputatio could be very sophisticated and, as an example, I discussed the "Controversy of Valladolid" (1550-51) on the status of the American Indians. Theological disputationes normally failed to harmonize truly incompatible positions, say, convincing Jews to become Christians (it was tried more than once, but you may imagine the results). But sometimes they did lead to good compromises and they kept the confrontation to the verbal level (at least for a while).

In modern science, the rules have changed a little, but the idea remains the same: experts try to convince their opponents using the best arguments they can muster. It is supposed to be a discussion, not a fight. Good manners are to be maintained and the fundamental feature is being able to speak a mutually understandable language. And not just that: the discussants need to agree on some basic tenets of the frame of the discussion. During the Middle Ages, theologians debated in Latin and agreed that the discussion was to be based on the Christian scriptures. Today, scientists debate in English and agree that the discussion is to be based on the scientific method.

In the early times of science, one-to-one debates were used (maybe you remember the famous debate about Darwin's ideas that involved Thomas Huxley and Archbishop Wilberforce in 1860). But, nowadays, that is rare. The debate takes place at scientific conferences and seminars where several scientists participate, gaining or losing "prestige points" depending on how good they are at presenting their views. Occasionally, a presenter, especially a young scientist, may be "grilled" by the audience in a small re-enactment of the coming of age ceremonies of Native Americans. But, most important of all, informal discussions take place all over the conference. These meetings are not supposed to be vacations, they are functional to the face-to-face exchange of ideas. As I said, scientists are human beings and they need to see each other in the face to understand each other. A lot of science is done in cafeterias and over a glass of beer. Possibly, most scientific discoveries start in this kind of informal setting. No one, as far as I know, was ever struck by a ray of light from heaven while watching a power point presentation.

It would be hard to maintain that scientists are more adept at changing their views than Medieval theologians and older scientists tend to stick to old ideas. Sometimes you hear that science advances one funeral at a time; it is not wrong, but surely an exaggeration: scientific views do change even without having to wait for the old guard to die. The debate at a conference can decisively tilt toward one side on the basis of the brilliance of a scientist, the availability of good data, and the overall competence demonstrated.

I can testify that, at least once, I saw someone in the audience rising up after a presentation and say, "Sir, I was of a different opinion until I heard your talk, but now you convinced me. I was wrong and you are right." (and I can tell you that this person was more than 70 years old, good scientists may age gracefully, like wine). In many cases, the conversion is not so sudden and so spectacular, but it does happen. Then, of course, money can do miracles in affecting scientific views but, as long as we stick to climate science, there is not a lot of money involved and corruption among scientists is not widespread as it is in other fields, such as in medical research.

So, we can imagine that in the 1980s the consensus machine worked as it was supposed to do and it led to the general opinion of climate scientists switching from cooling to warming. That was a good thing, but the story didn't end with that. There remained to convince people outside the narrow field of climate science, and that was not obvious.

From the 1990s onward, the disputatio was dedicated to convincing non-climate scientists, that is both scientists working in different fields and intelligent laypersons. There was a serious problem with that: climate science is not a matter for amateurs, it is a field where the Dunning-Kruger effect (people overestimating their competence) may be rampant. Climate scientists found themselves dealing with various kinds of opponents. Typically, elderly scientists who refused to accept new ideas or, sometimes, geologists who saw climate science as invading their turf and resenting that. Occasionally, opponents could score points in the debate by focusing on narrow points that they themselves had not completely understood (for instance, the "tropospheric hot spot" was a fashionable trick). But when the debate involved someone who knew climate science well enough the opponents' destiny was to be easily steamrolled.

These debates went on for at least a decade. You may know the 2009 book by Randy Olson, "Don't be Such a Scientist" that describes this period. Olson surely understood the basic point of debating: you must respect your opponent if you aim at convincing him or her, and the audience, too. It seemed to be working, slowly. Progress was being made and the climate problem was becoming more and more known.

These debates went on for at least a decade. You may know the 2009 book by Randy Olson, "Don't be Such a Scientist" that describes this period. Olson surely understood the basic point of debating: you must respect your opponent if you aim at convincing him or her, and the audience, too. It seemed to be working, slowly. Progress was being made and the climate problem was becoming more and more known.

And then, something went wrong. Badly wrong. Scientists suddenly found themselves cast into another kind of debate for which they had no training and little understanding. You see in Google Ngrams how the idea that climate change was a hoax lifted off in the 2000s and became a feature of the memesphere. Note how rapidly it rose: it had a climax in 2009, with the Climategate scandal, but it didn't decline afterward.

It was a completely new way to discuss: not anymore a disputatio. No more rules, no more reciprocal respect, no more a common language. Only slogans and insults. A climate scientist described this kind of debate as like being involved in a "bare-knuckle bar fight." From there onward, the climate issue became politicized and sharply polarized. No progress was made and none is being made, right now.

Why did this happen? In large part, it was because of a professional PR campaign aimed at disparaging climate scientists. We don't know who designed it and paid for it but, surely, there existed (and still exist) industrial lobbies which were bound to lose a lot if decisive action to stop climate change was implemented. Those who had conceived the campaign had an easy time against a group of people who were as naive in terms of communication as they were experts in terms of climate science.

The Climategate story is a good example of the mistakes scientists made. If you read the whole corpus of the thousands of emails released in 2009, nowhere you'll find that the scientists were falsifying the data, were engaged in conspiracies, or tried to obtain personal gains. But they managed to give the impression of being a sectarian clique that refused to accept criticism from their opponents. In scientific terms, they did nothing wrong, but in terms of image, it was a disaster. Another mistake of scientists was to try to steamroll their adversaries claiming a 97% of scientific consensus on human-caused climate change. Even assuming that it is true (it may well be), it backfired, giving once more the impression that climate scientists are self-referential and do not take into account objections of other people.

Let me give you another example of a scientific debate that derailed and become a political one. I already mentioned the 1972 study "The Limits to Growth." It was a scientific study, but the debate that ensued was outside the rules of the scientific debate. A feeding frenzy among sharks would be a better description of how the world's economists got together to shred to pieces the LTG study. The "debate" rapidly spilled over to the mainstream press and the result was a general demonization of the study, accused to have made "wrong predictions," and, in some cases, to be planning the extermination of humankind. (I discuss this story in my 2011 book "The Limits to Growth Revisited.") The interesting (and depressing) thing you can learn from this old debate is that no progress was made in half a century. Approaching the 50th anniversary of the publication, you can find the same criticism republished afresh on Web sites, "wrong predictions", and all the rest.

So, we are stuck. Is there a hope to reverse the situation? Hardly. The loss of the capability of obtaining a consensus seems to be a feature of our times: debates require a minimum of reciprocal respect to be effective, but that has been lost in the cacophony of the Web. The only form of debate that remains is the vestigial one that sees presidential candidates stiffly exchanging platitudes with each other every four years. But a real debate? No way, it is gone like the disputes among theologians in Middle Ages.The discussion on climate, just as on all important issues, has moved to the Web, in large part to the social media. And the effect has been devastating on consensus-building. One thing is facing a human being across a table with two glasses of beer on it, another is to see a chunk of text falling from the blue as a comment to your post. This is a recipe for a quarrel, and it works like that every time.

Also, it doesn't help that international scientific meetings and conferences have all but disappeared in a situation that discourages meetings in person. Online meetings turned out to be hours of boredom in which nobody listens to anybody and everyone is happy when it is over. Even if you can still manage to be at an in-person meeting, it doesn't help that your colleague appears to you in the form of a masked bag of dangerous viruses, to be kept at a distance all the time, if possible behind a plexiglass barrier. Not the best way to establish a human relationship.

This is a fundamental problem: if you can't build a consensus by a debate, the only other possibility is to use the political method. It means attaining a majority by means of a vote (and note that in science, like in theology, voting is not considered an acceptable consensus building technique). After the vote, the winning side can force their position on the minority using a combination of propaganda, intimidation, and, sometimes, physical force. An extreme consensus-building technique is the extermination of the opponents. It has been done so often in history that it is hard to think that it will not be done again on a large scale in the future, perhaps not even in a remote one. But, apart from the moral implications, forced consensus is expensive, inefficient, and often it leads to dogmas being established. Then it is impossible to adapt to new data when they arrive.

So, where are we going? Things keep changing all the time; maybe we'll find new ways to attain consensus even online, which implies, at a minimum, not to insult and attack your opponent right from the beginning. As for a common language, after that we switched from Latin to English, we might now switch to "Googlish," a new world language that might perhaps be structured to avoid clashes of absolutes -- perhaps it might just be devoid of expletives, perhaps it may have some specific features that help build consensus. For sure, we need a reform of science that gets rid of the corruption rampant in many fields: money is a kind of consensus, but not the one we want.

h/t Carlo Cuppini and "moresoma"

Good Morning Ugo, I hope that all is well with you.

ReplyDeleteIn a way you have described perfectly the reason that I walked away from being a scientist thirteen years ago.

But I just want to run this up the flagpole and see who here salutes it.

I think that the real problem that "Scientists" have is that the very thing that makes them scientists has somehow become the very thing that makes people distrust them. We have made "scientists" our new priesthood and right now the fractured and narrow nature of the requirements of the individual disciplines have made up a bunch of competing "sects" who strive mightily for converts and followers.

So you have a fractured church. Add into this the pervasive and corrupting influence of money and status and you have a pretty poisonous and unattractive facade trying to convince people of urgency.

Another real problem is the nature of scientific communication with the plethora of "Journals" each attempting to limit the range of discussion and each dependent on their advertisers to make the payroll and more often than not making publication choices on economic rather than scientific grounds (JAMA and NEJM are excellent examples). I suppose that I see these publications as serving the role of medieval bishoprics.

Finally, there is a problem of showmanship. Our cultures have elevated snarky, nasty arguments to the status of "preferred entertainment".

I don't see any consensus happening because no one really wants one.

That's the situation, unfortunately. One of the reasons is that the personal integrity of single scientists has never been considered as an important element of science. And now we see the results. It always brings to my mind Heinlein's "Stranger in a Strange Land" with his wonderful invention of the "Fair Witnesses." Will we ever be able to grok these ideas?

DeleteNot meaning to beat a dead horse, but a lot of the problem as simply a problem of scientists not feeling a responsibility to treat others as equals. So much of any conversation with a majority of scientists (my informal estimate is around 70%) ends up with the assertion that they are smarter than you are so you should just shut up and do what you are told.

DeleteThis even occurs in conversations between peers.

By now, the poor horse is not just dead, but mashed into a bloody mess. And for good reasons, unfortunately!

Delete

DeleteI have to second degringolade on his assessment of scientists, I’ve found that the most pigheaded and intellectually arrogant individuals I’ve ever met have been scientists,they seem to think that having a science degree, usually in a very narrow specialty turns them into superior beings with the ability to pontificate on nearly any subject. They’re also vain and silly beings whose primary personal concerns seem to be about career, perks and promotions.

It's the results of the majority of scientists today are mediocrities who are very good at playing the grant and publication system of today's bureaucratic Science System, unfortunately they also excel in the capacity to get promoted to the top positions. It’s like what has happened to the Church, the sort of man who in the early days would have become a Saint and/or Church Father remains a parish priest or a layman while higher Church office seems all too often to be the express lane to Hell…

Now this is not simply a problem with the scientists, it flows out of the institutional context in which science is done today. Today’s Bureaucratic-Imperial Power System will not tolerate an independent Science any more than it will tolerate an independent Press, what it wants is a captive servile Science that will build weapons and engineer the correct RealityTM. A system that favors the rise of pandering mediocrities who excel in telling the powerful what they want to hear.

Ugo, have you heard of how the majority of Canada’s scientific archives were destroyed under Stephen Harper? He’s now gone from the Premier’s office but the atmosphere for science hasn’t improved. The massive destruction of culture at the end of a civilization is not a result of the Fall, it actually precedes it and is ordered by its decadent elites in a last ditch effort to keep themselves in power. The Church and the barbarian rulers who succeeded Rome actually carried out a massive salvage operation that preserved what little had survived the carnage. The Dark Ages aren't in the future, it's now!

To preserve Science you have to turn to ordinary people and learn to speak to them with respect, they’re not the enemies of Science as the class snobs and courtly panderers say, they’re people searching for real guidance to replace an elite that has betrayed them, the real enemies of science are the powerful and their courtiers. After all, look at history, the declining Roman Empire attempted to enslave the Church and promoted heresies, Arianism, Iconoclasm, it persecuted clergymen, Saint John Chrysostom, Maximus the Confessor who died in exile. Turning toward the Franks, the baptism of Clovis, turning away from the crumbling world of the Empire, was the beginning of a new world, that of Medieval Christendom.

Away from the City of Man, toward the City of God!

Two events have happened in the last few months, both involving large companies, that may lead to a new form of consensus. The first event is that many of these companies (including oil majors such as Occidental and BP) have committed to some form of the ‘Net Zero emissions’ goal. The second event is that many companies are now making COVID vaccination a condition of employment.

ReplyDeleteIt is easy to be cynical about these moves, and to question the sincerity of management, particularly with regard to Net Zero goals. But these actions matter. People will find paid work associated with non-fossil fuel energy; others will accept the need to be vaccinated. They will then find that they are defending their decisions in front of others and thereby shifting the consensus.

Baghdad School for Scepticism & Certainty Studies...

ReplyDeleteOur Western Civilisation has tempered with Knowledge to escape the Energy Question;

The outstanding David Rutlege of Caltech, among armies of other beautiful minds earlier, has calculated that there is no enough fossil fuels remaining to alter the climate, even by the modest of all IPC's studies (link).

Diana Drake's book, Stealing from the Saracens, has outlined the flow of building styles and ideas, East and West (Saracens thought to mean Thieves, a name the Western scholars found in history for Arabs, discounting Thieves don't need to develop a luxury, rich, functional, sophisticated language like Arabic).

Baghdad School for Scepticism and Certainty Studies is an emerging initiative aims to address what is in Knowledge produced during our Western Civilisation has been an effort of Social Engineering, nothing for the sake of true Knowledge.

The disappointing legacy of of the Western Civilisation is that it has not weighed on the little value of tempered Knowledge to the value of what finite Energy is burned in that tempering.

Today, that tempering with Knowledge feared is ending up no less than a vicious Energy game.

"Energy, like time, flows from past to future".

Wailing.

Science is not about consensus. It is about what can be proved with a repeatable experiment. Science is not determined by voting. "Science advances one funeral at a time".

ReplyDeleteI hope you don't mind if I disagree with you, 5guns. This is what they teach you in high school, but the real world is a little different.

Deletei would let anther speak for me;

Delete“Science commits suicide when it adopts a creed.”

― Thomas Henry Huxley

“The scientific spirit is of more value than its products, and irrationally held truths may be more harmful than reasoned errors.”

― Thomas Henry Huxley, Collected Essays of Thomas Henry Huxley“

History warns us that it is the customary fate of new truths to begin as heresies and to end as superstitions.”

― Thomas Henry Huxley

While I understand the concepts behind 'consensus-building' in scientific communities (reading Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is a huge factor in my understanding), some of my observations I made during my decade chasing four university degrees were that: the exact same data could be interpreted in diametrically-opposed ways by researchers/scientists; debate between faculty members was at times extremely cantankerous (sometimes over the most trivial aspects); publish or perish mentality was significant, particularly for those seeking tenure; psychological and social mechanisms were oftentimes more 'persuasive' than the 'facts'; money (in the form of grants/corporate sponsorship) played a not non-significant role in both subject matter and interpretation of data.

ReplyDeleteI came away from that experience with the view that the goal of ‘objective truth’, as it were, was an ideal that could never be achieved regardless of how well meaning and dedicated scientists might be given their fallibility as social beings with powerful psychological mechanisms that impact their perceptions. ‘Science’ is a methodological process to help us attempt to understand the world but is also a means of creating narratives that may or may not reflect ‘reality’. A recent paper I read opens with something similar (and better than I could state): “We begin with a reminder that humans are storytellers by nature. We socially construct complex sets of facts, beliefs, and values that guide how we operate in the world. Indeed, humans act out of their socially constructed narratives as if they were real. All political ideologies, religious doctrines, economic paradigms, cultural narratives—even scientific theories—are socially constructed “stories” that may or may not accurately reflect any aspect of reality they purport to represent. Once a particular construct has taken hold, its adherents are likely to treat it more seriously than opposing evidence from an alternate conceptual framework.” (https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/14/15/4508/htm?fbclid=IwAR2ISt5shfV4wpFEc8jxbQnrrxyllyvZP-xDnoHhWrjGTQRIqUNfk3hOK1g)

One must have ‘faith’ in ‘science’, it would seem, as much as one must have faith in any enterprise. While ‘consensus’ is an ideal, the force with which politicians seem to be using to attain it recently has many losing faith…

Very well said, Steve. Let me just add that the situation has considerably worsened in recent years. I have been in academia for more than 40 years, and I can see the involution. Once, it was still possible to carry a minority idea into a debate. Now, it has become almost impossible, unless you belong to the "right" power-holding group. And it keeps getting worse every day!!!

DeleteSending a couple of comments as my original is too long apparently.

DeletePart One

So, I was pondering your article further while working in my food gardens today (another 40+ degree day with the humidity here north of Toronto) and was thinking about the political use of ‘science’ to rationalise/justify policies/actions. This, of course, is nothing new. Science, like any other human enterprise, is leveraged by the ruling class to legitimise their behaviour for a wider audience—the entire eugenics movement became of interest to me as an undergraduate after being exposed to Stephen Jay Gould’s work. This (ab)use by politicians will certainly add to the mistrust/derision of science by some (many?) given the increasing loss of trust/faith in our ruling class.

I was contemplating that the scientific/medical ‘advisors’ that are being drawn upon for their ‘expertise’ were no longer practising ‘scientists’ or ‘doctors’. These are individuals who have progressed through the system to positions that are for the most part ‘political’ in nature and action. These are basically politicians with a training in some field of science/medicine. We are not so much being advised by ‘scientists’, therefore, but by other politicians.

As a retired educator (10 years as a classroom teacher and 15 as an elementary school administrator) with experience in both the teachers’ federation (union) and in the principals’ council (political association) at the local and provincial level, I witnessed many colleagues advance through the ‘ranks’ from teacher to vice principal to principal to superintendent to director of education. For many, their conversion from practising teacher to a higher position within the education system led them to take on a far more political stance in their language, behaviour, and educational actions.

Part Two

DeleteThis is of course natural. One’s changing position from a practitioner of a skill to a leadership role necessitates a different perspective and associated behaviours. Often, especially if the positional change requires removal from the practising environment, leadership skills replace the skills/knowledge of the practising person. Some retain a minimal connection to the practice but most, in my experience, shift completely to a leadership/political style of behaviour and actions. These are no longer practitioners; these are ‘politicians’ working with and surrounded by other ‘politicians’.

It then struck me that medical training (and various other related fields of study) may not even delve very deeply or at all into the history and/or philosophy of science where one studies far more extensively the development of and specific aspects of the scientific method; something that seems quite necessary to be deemed an scientific ‘expert’. Having a sibling who is a medical specialist (gynecological oncologist) and married to another medical specialist (orthopaedic surgeon with previous training as a physiotherapist), I posed some questions to her. Sure enough, unless one specifically takes some undergraduate courses in the history or philosophy of science, the only education one receives on these topics is that that might be covered tangentially in a biology, physics, or chemistry class. And given that some enter medicine without even these courses, that may be absent.

In fact, my educational background (chasing four degrees in several different disciplines and purposely taking history and philosophy of science courses because of my interest in the subject matter) far exceeds my sibling’s and her husband’s combined education in these areas. They, rightly so, spent their time studying and training in the medical model/paradigm and their specialties.

So, here’s my working hypothesis: the people we are pointing to as our science ‘experts’ (and I hate the term ‘expert’, reminding myself constantly of Nassim Taleb’s perspective that “experts don’t know what they don’t know”) are not trained in ‘science’ (at least the methodology and all its historical/philosophical baggage) much if at all; they are ‘trained’ in a specific field within a specific paradigm. Add to this the observation that they are for all intents and purposes ‘politicians’ and no longer practising ‘researchers/doctors’, then one can only conclude that we are not pursuing ‘science’ as such but ‘politics’.

Thoughts??

It is impossible for me (as a rather well read layman) to keep current with Science with a capital "S".

ReplyDeleteI assume it's extremely difficult if not actually impossible for a working scientist (ie. a chemist or biologist) to to keep current with other sciences like physics or atmospheric studies.

So of course, we have to take Science on faith, trusting the system even if we may not trust an individual scientist.

And what is an acceptable proof in one field (Archeology and "Social Sciences") wouldn't make the cut in physics. Sometimes Science isn't very scientific.

The media was very much guilty of not publishing anything on climate science once advertisers refused to run their ads next to a climate change story. Apparently the end of the world stories didn't motivate people to buy .

Now the algorithms at Facepalm and Twitter push the true science off the feeds b/c the fake science pulls more eyeballs.

And there are tons of pdfs on the web that look like scientific papers but are purely disinformation, paid for by corporations with something to sell.

So yeah, we need some way to communicate what is and what isn't credible.

Not every man in a white lab coat is a scientist.

This is all reminiscent of the medieval argument about whether a corrupt priest can offer a genuine sacrament.

Impressive how some people understood so well my position. And how so few criticized it. I think it is an indication that science is truly collapsing. Also, agree with me that neglecting to take into account the personal honesty and integrity of individual scientists is leading science straight to hell. We would need something like "barefoot scientists" inspired by St. Francis. Or maybe some kind of "fair witnesses" as described by Heilein in his "Stranger in a Strange Land." We should have thought about that much earlier, alas....

ReplyDeleteI think this is because the covid crisis has been like a revelation about how science works (in the real world, I mean, not the world we would like to live in). I would have not believed it only 2 years ago.

DeleteIndeed, the Covid has been a watershed. It was equivalent to when, in 1517, Pope Leo X authorized the sale of indulgences in Germany. Latr in the same year, Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses on the door of the church of Wittemberg. I think something similar needs to happen, now.

DeleteYes, along with the three laws of robotics and basic psychohistory from Asimov. But if people don't learn from history, why would we learn from fiction?

ReplyDeleteDo you think there is a correlation between the development of the scientific method, and the burning of fossil fuels so as to access cheap plentiful energy?

ReplyDeleteIf so, does the science enable the energy harvesting, or does the abundant energy allow the development of ever more complex science?

i.e. is science a part of the ever increasing complexity of "western civilisation"?

And so, if we understand that ECoE is rising, fossil fule production is slowing, and that we are looking at involuntary de-growth in the future, is the unwinding of science a part of that forced reduction in complexity due to reduction in the availability of energy?

I would argue that indeed the exploitation of fossil fuels has 'fuelled' scientific development very much. It has not only allowed the expansion of the endeavour by providing us with more and more energy 'slaves' so as to increase the numbers of people engaged in the pursuit, but also the creation of specific 'specialties' and their hyper-focus on particular questions. It has also led to significant technological developments that have permitted us a deeper look into certain aspects of our universe. And, yes, we are likely to lose much of our complexities, including much of 'science', as our regression to the mean of human living standards proceeds.

DeleteYes... but I guess I was wondering if the breakdown of the consensus building networking was a symptom of that? Or is it an unrelated thing?

DeleteI'm looking for ways to assess the overall complexity of society, and trying to see if it is increasing or decreasing. I don't know if it is possible for it to decrease without major disasters (war, disease, mass die-off)

Is our complexity increasing or decreasing? It probably depends on what/where you're looking. If you've not read archaeologist Joseph Tainter's The Collapse of Complex Societies, I would suggest doing so to provide some insight.

Delete

ReplyDeletePerhaps everyone here already knows these links that help people who are not climate scientists to understand how climate denial works. Just in case, someone has not found them, here they are:

1.Climate Change -- the scientific debate

Made in 2008 by retired science journalist ‘Potholer 54’ Paul Hadfield, this is the first video of a great series

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52KLGqDSAjo&list=PL82yk73N8eoX-Xobr_TfHsWPfAIyI7VAP

Skeptical Science the go to site for debunking - here are 3 links there are many more pages it is worth the time to explore

a) opening page including a clear and open identification of who the contributors

https://skepticalscience.com

b) refutation of 198 myths or ‘arguments’ for denial https://skepticalscience.com/argument.php

c) 11 characteristics of pseudoscience

https://skepticalscience.com/11-characteristics-of-pseudoscience.html

Cheers,

ReplyDeletePerhaps everyone here already knows these links that help people who are not climate scientists to understand how climate denial works. Just in case someone has not found them, here they are:

1.Climate Change -- the scientific debate

Made in 2008 by retired science journalist ‘Potholer 54’ Paul Hadfield, this is the first video of a great series

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52KLGqDSAjo&list=PL82yk73N8eoX-Xobr_TfHsWPfAIyI7VAP

Skeptical Science the go to site for debunking - here are 3 links there are many more pages it is worth the time to explore

a) opening page including a clear and open identification of the contributors

https://skepticalscience.com

b) refutation of 198 myths or ‘arguments’ for denial https://skepticalscience.com/argument.php

c) 11 characteristics of pseudoscience

https://skepticalscience.com/11-characteristics-of-pseudoscience.html

ReplyDeletePerhaps everyone here already knows these links that help people who are not climate scientists to understand how climate denial works. Just in case someone has not found them, here they are:

1.Climate Change -- the scientific debate

Made in 2008 by retired science journalist ‘Potholer 54’ Paul Hadfield, this is the first video of a great series

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52KLGqDSAjo&list=PL82yk73N8eoX-Xobr_TfHsWPfAIyI7VAP

Skeptical Science the go to site for debunking - here are 3 links there are many more pages it is worth the time to explore

a) opening page including a clear and open identification of the contributors

https://skepticalscience.com

b) refutation of 198 myths or ‘arguments’ for denial https://skepticalscience.com/argument.php

c) 11 characteristics of pseudoscience

https://skepticalscience.com/11-characteristics-of-pseudoscience.html

Ugo: This one has made me think far to much. I see where you are coming from and I don't wholly approve or disapprove.

ReplyDeleteLet me think about this for a day or two and I will write something over at my place in response.

There are a bunch of traps and land mines down this path. I have to be careful.

Thanks a lot for this one, makes this old brain work.

I'm glad I wasn't drinking coffee when I read, "No one, as far as I know, was ever struck by a ray of light from heaven while watching a power point presentation."

ReplyDeleteYour essay was a perfect response.

The major problem with referring to a consensus is that it doesn't mean what it should. A consensus in science should be that a large body of scientists agree that the scientific method was followed without bias to reach a singular conclusion. What the public hears is that a bunch of scientists believe something is true in their own opinion. In other words, they hear, "I'm a scientist, and you should listen to me because I'm smart". They don't hear "scientists followed a rigorous method that considered as many other possibilities as plausible to arrive at a result with X level of certainty". It doesn't help that science is becoming more political and also more competitive so that the prize for producing results, regardless of how sloppy the research, is given to those who "helped the field" or who "got there first".

ReplyDeleteI was tempted to post this Youtube URL because there are some of the original members of the Club of Rome discussing ideas that still perplex us:

ReplyDeletehttps://youtu.be/cCxPOqwCr1I