The Scientific Method

Galileo Galilei is correctly remembered as the father of modern science because he invented what we call today the "scientific method," sometimes still called the "Galilean method." It is supposed to be the basis of modern science; the feature that makes it able to be called "Science" with a capital first letter, as we were told over and over during the Covid pandemic. But what is really this scientific method that's supposed to lead us to the truth? Galileo's paradigmatic idea was an experiment about the speed of falling objects. It is said that he took two solid metal balls of different weights and dropped them from the top of the Pisa Tower. He then noted that they arrived at the ground at about the same time. That allowed him to lampoon an ancient authority such as Aristotle for having said that heavier objects fall faster than lighter ones (*). There followed an avalanche of insults to Aristotle that continues to this day. Even Bertrand Russel fell into the trap of poking fun at Aristotle, accused of having said that women have fewer teeth than men. Too bad that he never said anything like that.

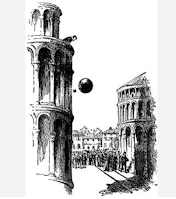

Galileo's paradigmatic idea was an experiment about the speed of falling objects. It is said that he took two solid metal balls of different weights and dropped them from the top of the Pisa Tower. He then noted that they arrived at the ground at about the same time. That allowed him to lampoon an ancient authority such as Aristotle for having said that heavier objects fall faster than lighter ones (*). There followed an avalanche of insults to Aristotle that continues to this day. Even Bertrand Russel fell into the trap of poking fun at Aristotle, accused of having said that women have fewer teeth than men. Too bad that he never said anything like that.The surrogate endpoint in medicine

How can you apply the scientific method in medicine? Dropping a sick person and a healthy one from the top of the Pisa Tower won't help you so much. The problem is the large number of parameters that affect the nebulous entity called "health" and the fact that they all strongly interact with each other.

So, imagine you were sick, and then you feel much better. Why exactly? Was it because you took some pills? Or would you have recovered anyway? And can you say that you wouldn't have recovered faster hadn't you taken the pill? A lot of quackery in medicine arises from these basic uncertainties: how do you determine what is the specific cause of a certain effect? In other words, is a certain medical treatment really curing people, or is it just their imagination that makes them think so?

Medical researchers have worked hard at developing reliable methods for drug testing, and you probably know that the "gold standard" in medicine is the "Randomized Controlled Test" (RCT). The idea of RCTs is that you test a drug or a treatment by keeping all the parameters constant except one: taking or not taking the drug. It is designed to avoid the effect called "placebo" (the patient gets better because she believes that the drug works, even though she is not receiving it) and the one called "nocebo" (the patient gets worse because he believes that the drug is harmful, even though he is not receiving it).

An RCT involves a complex procedure that starts with separating the patients into two similar groups, making sure that none of them knows to which group she belongs (the test is "blinded"). Then, the members of one of the two groups are given the drug, say, in the form of a pill. The others are given a sugar pill (the "placebo"). After a certain time, it is possible to examine if the treatment group did better than the control group. There are statistical methods used to determine whether the observed differences are significant or not. Then, if they are, and if you did everything well, you know if the treatment is effective, or does nothing, or maybe it causes bad effects.

For limited purposes, the RCT approach works, but it has enormous problems. A correctly performed RCT is expensive and complex, its results are often uncertain and, sometimes, turn out to be plain wrong. Do you remember the case of "Thalidomide"? It was tested, found to work as a tranquilizer, and approved for general use in the 1960s in Europe. It was later discovered that it had teratogenic effects on fetuses, and some 10.000 babies in Europe were born without arms and legs before the drug was removed from the market. Tests on animals would have shown the problem, but they were not performed or were not performed correctly.

Of course, the rules have been considerably tightened after the Thalidomide disaster and, nowadays, testing on animals is required before a new drug is tested on humans. But let's note, in passing, that in the case of the mRNA Covid vaccines, tests on animals were performed in parallel (and not before) testing on humans. This procedure exposed volunteers to risks that normally would not be considered acceptable with drug testing. Fortunately, it does not appear that mRNA vaccines have teratogenic effects.

Even assuming that the tests are complete, and performed according to the rules, there is another gigantic problem with RCT: What do you measure during the test? Ideally, drugs are aimed at improving people's health, but how do you quantify "health"? There are definitions of health in terms of indices called QALY (quality-adjusted life years) or QoL (quality of life). But both are difficult to measure and, if you want long-term data, you have to wait for a long time. So, in practice, "surrogate endpoints" are used in drug testing.

A surrogate endpoint aims at defining measurable parameters that approximate the true endpoint -- a patient's health. A typical surrogate endpoint is, for instance, blood pressure as an indicator of cardiovascular health. The problem is that a surrogate endpoint is not necessarily related to a person's health and that you always face the possibility of negative effects. In the case of drugs used to treat hypertension, negative effects exist and are well known, but it is normally believed that the positive effects of the drug on the patient's health overcome the negative ones. But that's not always the case. A recent example is how, in 2008, the drug bevacizumab was approved in the US by FDA for the treatment of breast cancer on the basis of surrogate endpoint testing. It was withdrawn in 2011, when it was discovered that it was toxic and that it didn't lead to improvements in cancer progression (you can read the whole story in "Malignant" by Vinayak Prasad).

Consider now another basic problem. Not only the number of parameters affecting people's health are many, but they strongly interact with each other, as is typical of complex systems. The problem may take the form called "polydrug use," and it especially affects old people who accumulate drugs on their bedstands, just like old cars accumulate dents on their bodies. An RCT test that evaluates one drug is already expensive and lengthy; evaluating all the possible combinations of several drugs is a nightmare. If you have two drugs, A and B, you have to go through at least three tests: A alone, B alone, and the combination of A+B. If you have three drugs, you have seven tests to do (A, B, C, AB, BC, AC and ABC). And the numbers grow rapidly. In practice, nobody knows the effects of these multiple drug uses, and, likely, nobody ever will. But a common observation is that when the elderly reduce the number of medicines they take, their health immediately improves (this effect is not validated by RCTs, but that does not mean it is not true. I noted it for my mother-in-law who died at 101).

The case of Face Masks

Some medical interventions have specific problems that make RCTs especially difficult. An example is that of face masks to prevent the spreading of an airborne pathogen. Evidently, there is no way to perform a blind test with face masks, but the real problem is what to use as a surrogate end-point. At the beginning of the Covid pandemic, several studies were performed using cameras to detect liquid droplets emitted by people breathing or sneezing with or without face masks. That was a typical "Galilean," laboratory approach, but what does it demonstrate? Assuming that you can determine if and how much a mask reduces the emission of droplets, is this relevant in terms of stopping the transmission of an airborne pathogen? As a surrogate endpoint, droplets are at best poor, at worst misleading.

A much better endpoint is the PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test that can directly detect an infection. But even here, there are many problems. As an example, consider an often touted study performed in Pakistan that claimed to have demonstrated the effectiveness of face masks. Let's assume that the results of the study are statistically significant (really?) and that nobody tampered with the data (and we can never be sure of that in such a heavily politicized matter). Then, the best you can say is that if you live in a village in Pakistan, if there is a Covid wave ongoing, if the PCR tests are reliable, if the people who wore masks behave exactly like those who don't, and if random noise didn't affect the study too much, then by wearing a mask you can delay being infected for some time, and maybe even avoid infection altogether. Does the same result apply to you if you live in New York? Maybe. Is it valid for different conditions of viral diffusion and epidemic intensity? Almost certainly not. Does it ensure that you don't suffer adverse effects from wearing face masks? Duh! Would that make you healthier in the long run? We have no idea.

The Pakistan study is just one example of a series of studies on face masks that were found to be ill-conceived, poorly performed, inconclusive, or useless in a recent rigorous review published in the Cochrane Network. The final result is that no one has been able to detect a significant effect of face masks on the diffusion of an airborne disease, although we cannot say that the effect is actually zero.

The confusion about face masks reached stellar levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, Tony Fauci, director of the NIAID, first advised against wearing masks, then he reversed his position and publicly declared that face masks are effective and even that two masks are better than just one. Additionally, he declared that the effectiveness of masks is "science" and, therefore, cannot be doubted. But, nowadays, Fauci has reversed his position, at least in terms of mask effectiveness at the population level. He still maintains that they can be useful for an individual "who religiously wears a mask." Now, imagine an RCT dedicated to demonstrating the different results of "religiously" and "non-religiously" wearing a mask. So much for science as a pillar of certainty.

Surrogate endpoints everywhere

Medicine is a field that may be defined as "science" since it is based (or should be based) on data and measurements. But you see how difficult it is to apply the scientific method to it. Other fields of science suffer from similar problems. Climate science, ecosystem science, biological evolution, economics, management, policies, and others are cases in which you cannot reproduce the main features of the system in a laboratory and, at the same time, involve a large number of parameters interacting with each other in a non-linear manner. You could say, for instance, that the purpose of politics is to improve people's well-being. But how could that be measured? In general, it is believed that the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a measure of the well-being of the economy and, hence, of all citizens. Then, it is concluded that economic growth is always good, and that it should be stimulated by all possible interventions. But is it true? GDP growth is another kind of surrogate endpoint used simply because we know how to measure it. But people's well-being is something that we don't know how to measure.

Is a non-Galilean science possible? We have to start considering this possibility without turning to discard the need for good data and good measurements. But, for complex systems, we have to move away from the rigid Galilean method and use dynamic models. We are moving in that direction, but we still have to learn a lot about how to use models and, incidentally, the Covid19 pandemic showed us how models can be misused and lead to various kinds of disasters. But we need to move on, and I'll discuss this matter in detail in an upcoming post.

______________________________________________

(*) Aristotle's "Physics" (Book VIII, chapter 10) where he discusses the relationship between the weight of an object and its speed of fall:"Heavier things fall more quickly than lighter ones if they are not hindered, and this is natural, since they have a greater tendency towards the place that is natural to them. For the whole expanse that surrounds the earth is full of air, and all heavy things are borne up by the air because they are surrounded and pressed upon by it. But the air is not able to support a weight equal to itself, and therefore the heavier bodies, as having a greater proportion of weight, press more strongly upon and sink more quickly through the air than do the lighter bodies."