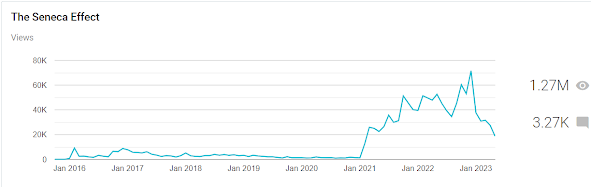

I just started a new blog titled "The Hydrogen Skeptics." It is about the hydrogen economy and hydrogen as a fuel and it is a little technical as a subject. So I thought it was not appropriate to discuss it in a somewhat philosophical blog like "The Seneca Effect." Yet, there are points in common, as I am arguing in this post. Above: the nuclear-powered car "Ford Nucleon", unfortunate technological prodigy of the 1950s, that never was turned into anything practical.

The Romans of imperial times found themselves in a situation not unlike ours. Gradually running out of resources, they found themselves more and more in trouble with keeping together a vast empire that was enormously expensive to defend and govern. Already at the time of Lucius Annaeus Seneca (1st century AD), it must have been clear to everyone that something was not running right in the very bowels of the giant organism that was the Empire. But what was wrong, exactly?

All societies are based on a fundamental "founding myth" that forms the justification of everything that was done and is being done. The Romans were not a technology-based civilization, and they would have been puzzled by our fixation on new gadgets. They were a military civilization that built its founding myth on the prowess of their soldiers and the efficiency of their armies. That, in turn, was believed to be the result of the Gods' benevolence who had rewarded the Romans for their virtues. The Romans were supposed to be brave, strong, and pious, and they never failed to perform the sacrifices that were due to please their Gods.

You can understand this attitude if you read Virgil's "Aeneid," (1st century AD), truly the foundation of the Roman view of the world. The hero and the central protagonist of the story is the Trojan warrior Aeneas, who goes through a series of adventures always careful to follow the advice of the Gods. He is neither dumb nor insensitive, but he never loses track of his mission. And the Gods, in turn, help him to achieve his goal. Being the son of a Goddess (Aphrodite) helps him a lot, too!

So, the Romans saw themselves as still performing Aeneas' mission when they conquered new lands and new peoples. The idea was to bring them civilization, (similar to our slogan "bring them democracy.") The Romans were genuinely convinced to be a superior civilization and that the manifest destiny of Barbarians was to become Romans. But things started going wrong and many Barbarians stubbornly refused to surrender to the glorious Roman armies. So, what was the problem? Had the Gods abandoned the Romans? Maybe it was because they were not anymore so virtuous as they used to be during the good times. Maybe the Romans had become lazy, maybe they had forgotten the proper sacrifice rituals.

One reaction was to return to the ancient virtues and to the ancient religion. We see this tendency during the whole period of decadence of the Empire, from the 1st century onward. We see it in the Stoic school of philosophy -- of which Seneca was a prominent member. Just like the mythical hero, Aeneas, Stoics emphasized personal virtue in difficult times. They would find their reward just in being virtuous, independently on whether they had succeeded or not in their task.

Stoics were not so convinced about the religious

practices and the many deities of their times. They tended to replace what they saw as silly beliefs with a loftier vision of a single, all-powerful spiritual entity. But they weren't iconoclasts. They were supporters of the traditional religions for those who didn't have the culture and the intelligence necessary to understand a higher level of spirituality. It is also possible that cultivating one's virtues, as Stoics were doing, was seen as a way to convince the Gods that they should continue to support the Romans, or maybe restart supporting them.

Despite many efforts, the diffusion of Stoicism didn't seem to help very much, and the situation moved from bad to worse. That may have been one of the reasons why the Romans tended to try to fix their founding myth by switching to new religions. So, they tended to deify their emperors, that is, to turn him into a God to be worshiped just like all the other Gods. Surely, being led by one of the members of the divine coterie would surely mean that the Gods won't let their brother in Rome alone to fight those hordes of bad-smelling barbarians. It was not an easy task to turn the man at the top into a God, since he normally was a homicidal psychopath, or a sexual predators, or a pervert -- often all these things together. And the effort didn't seem to help so much, either.

Another strategy, a little more radical, was to import new religions from abroad. During the first two centuries of the Empire, Rome was truly a supermarket of Oriental religions. In some cases, new deities were incorporated into the existing Pantheon: Cybele, Isis, Mithras, and more. In other cases, entire new cults were transplanted into the Empire: Manichaeists, Zoroastrians, Mithraists, Jews, Christians, and more.

Eventually, one of these Oriental religions, Christianity, managed to get the upper hand over the others and it merged with the Emperor's cult. Constantine "The Great" (272 – 337 AD) saw himself as a divinely appointed emperor, but also a supporter of Christianity. From then on, apart for brief intervals, the Roman Empire was ruled by Christian Emperors. Theodosius "The Great" (347 – 395) officially banned Paganism from the Empire.

As we all know, these efforts didn't work so well. Despite the new faith and the divine emperors, the founding myth of the Roman Empire was hopelessly obsolete. The Empire faded away. It had to: God's benevolence was not enough to keep it together. The new founding myths were Christianity (without divine emperors) for Europe and Islam for the Middle East and Northern Africa. They ushered new kinds of societies, better adapted to the new times.

In time, Christianity lost its role as the founding myth of the European society. We tend to see the European world dominance as the result not of God's benevolence, but of our technological prowess. Our technological tricks are what keeps the modern Global Empire together and we seem to be convinced that, if we have problems, all we need to do is to invent new tricks -- new founding myths. The consequence is that all the problems we face can be removed by more technology.

But, in this phase of decline, it is clear that the Global Empire has enormous problems: running out of fossil fuels, pollution, global warming, social unrest, economic crisis, and more. So, we are trying to revamp and keep alive our founding myths.

Just like in ancient Roman Times, we are in a phase of a plethora of new myths that compete to get the upper hand as the new, improved founding myth. Our equivalent of Stoicism is the idea that we should be virtuous by saving energy and separating household waste. Another "mythlet" is the idea that our problem with fossil fuels, can be solved by switching to another fuel

(hydrogen) supposed to be both more abundant and cleaner.

The hydrogen myth is on a par with others that try to repair a damaged machine on the run. Some of these ideas are purely mythological, including the various nuclear technologies supposed to create energy out of nothing (the nuclear water boiler, the e-cat, is a good example). But some of these ideas are technically valid, just don't expect them to be the new founding myths for something that has to disappear anyway. Just as Christianity survived the end of the Roman Empire, some technologies that we are developing nowadays will survive the collapse of the Global Empire. Wind, solar, hydro, and others can provide energy, but they'll support a society that will be completely different from the current one.

So, why couldn't hydrogen be one of these technologies that will survive? It is because of technical reasons: hydrogen as a fuel has many problems that make it unsuitable for uses other than niche applications. Thinking of hydrogen on a grand scale as supporting a society as complex and wasteful as ours is simply a dream. Nevertheless, hydrogen remains popular nowadays just because of this impossible promise -- it is like a politician that gets elected by promising things that he will never be able to deliver.

For this reason, we need an in-depth discussion to understand what hydrogen can, and cannot, do and avoid that it becomes a stumbling block in the transition away from fossil fuels that we are facing. That's why I created a new blog titled "The Hydrogen Skeptics" In the introduction to the new blog, I write:

I

am not against hydrogen in itself, which is just a natural element

among 92 others. And I am open to the possibility that energy

technologies based on hydrogen may find applications in the future. I

am skeptical about the hype that surrounds hydrogen technologies. Not

all technologies turn out to be feasible, no matter how hyped. Just

think of the Ford Nucleon, nuclear powered car of the 1950s, shown in

the cover image.

So, if you want to take a look at the new blog, click on the image of the unfortunate Ford Nucleon, taken as an example of technological hubris, one more revolutionary idea that never worked.

Right now, there is only one post on the new blog, but I plan new posts soon and the blog is open for discussion. If you are interested to contribute, just write to me.