Overfishing, Conservation, Sustainability, and Farmed Fish

As with many other aspects of government policy, overfishing and other fishing-related environmental issues are a real problem, but it’s not clear that government intervention is the solution. Indeed, it might be one of the main drivers of overfishing and other conservation and sustainability issues stemming from commercial fishing. Much like drone fishing, there are serious ethical issues of interest to the average angler.

There’s another commonality that overfishing has with environmental issues more broadly: The Western companies primarily concerned with serious efforts to curb overfishing are not the ones who are most guilty of overfishing. What this means is that the costs of overfishing are disproportionately borne by the countries least engaged in practices that are counter to efforts to make commercial fishing more sustainable while also promoting conservation of fish biodiversity.

All of these are important issues not just for commercial fishermen, but also those interested in questions of conservation and sustainability in general, as well as recreational fisherman and basically anyone who uses fish as a food source. As the ocean goes, so goes the planet, so it is of paramount importance for everyone to educate themselves on what is driving overfishing, what its consequences are, and what meaningful steps — not simply theater to feel as if “something is being done” — can be taken.

Indeed, over three billion people around the world rely on fish as their primary source of protein. About 12 percent of the world relies on fisheries in some form or another. 90 percent of these being small-scale fishermen — “think a small crew in a boat, not a ship,” using small nets or even rods, reels and lures not too different from the kind you probably use.

There are 18.9 million fishermen in the world, with 90 percent of them falling under the same small-scale fisherman rubric discussed above.

Overfishing Definition: What is Overfishing?

First, take heart: As a recreational fisherman you are almost certainly not guilty of “overfishing.” This is an issue for commercial fishermen in the fishing industry who are trawling the ocean depths with massive nets to catch enough fish to make a living for themselves and their families, not the angler who enjoys a little peace and quiet on the weekends.

Overfishing is, in some sense, a rational reaction to increasing market needs for fish. Most people consume approximately twice as much fish as they did 50 years ago and there are four times as many people on earth as there were at the close of the 1960s. This is one driver of the 30 percent of commercially fished waters being classified as “overfished.” This means that the stock of available fishing waters are being depleted faster than they can be replaced.

There is a simple and straightforward definition of when an area is being “overfished” and it’s not simply about catching “too many” fish. Overfishing occurs when the breeding stock of an area becomes so depleted that the fish in the area cannot replenish themselves.

At best, this means fewer fish next year than there are this year. At worst, it means that a species of fish cannot be fished out of a specific area anymore. This also goes hand-in-hand with wasteful forms of fishing that harvest not just the fish the trawler is looking for, but just about every other organism big enough to be caught in a net. Over 80 percent of fish are caught in these kinds of nets but fish aren’t the only things caught in nets.

What’s more, there are a number of wide-reaching consequences of overfishing. It’s not simply bad because it depletes the fish stocks of available resources, though that certainly is one reason why it’s bad. Others include:

- Increased Algae in the Water: Like many other things, algae is great but too much of it is very bad. When there are fewer fish in the water, algae doesn’t get eaten. This increases the acidity in the world’s oceans, which negatively impacts not only the remaining fish, but also the reefs and plankton.

- Destruction of Fishing Communities: Overfishing can completely destroy fish populations and communities that once relied upon the fish that were there. This is particularly true for island communities. And it’s worth remembering that there are many isolated points on the globe where fishing isn’t just the driver of the economy, but also the primary source of protein for the population. When either or both of these disappear, the community disappears along with it.

- Tougher Fishing for Small Vessels: If you’re a fan of small business, you ought to be concerned about overfishing. That’s because overfishing is mostly done by large vessels and makes it harder for smaller ones to meet their quotas. With over 40 million people around the world getting their food and livelihood from fishing, this is a serious problem.

- Ghost Fishing: Ghost fishing refers to abandoned man-made fishing gear that is left behind. It’s believed that an estimated 25,000 nets float throughout the Northeast Atlantic. This left behind gear becomes a death trap for all marine life that swim through that area. While much of this is caused due to storms and natural disasters, much of it is the result of ignorance and neglect on behalf of commercial fishermen.

- Species Pushed to Near Extinction: When we hear that a fish species is being depleted, we often think it’s fine because they can be found somewhere else. However, many species of fish are being pushed close to extinction by overfishing, such as several species of cod, tuna, halibut and even lobster.

- Bycatch: If you’re old enough to remember people being concerned about dolphins caught in tuna nets, you know what bycatch is: It’s when marine life that is not being sought by commercial fishermen is caught in their nets as a byproduct. The possibility of bycatch increases dramatically with overfishing.

- Waste: Overfishing creates waste in the supply chain. Approximately 20 percent of all fish in the United States is lost in the supply chain due to overfishing. In the Third World this rises to 30 percent thanks to a lack of available freezing devices. What this means is that even though there are more fish being caught than ever, there is also massive waste of harvested fish.

- Mystery Fish: Because of overfishing, there are a significant amount of fish at your local fish market and on the shelves of your local grocery store that aren’t what they are labelled as. Just because something says that it’s cod doesn’t mean that it actually is. To give you an idea of the scope of this problem, only 13 percent of the “red snapper” on the market is actually red snapper. Most of this is unintentional due to the scale of fishing done today, but much of it is not, hiding behind the unfortunate realities of mass scale fishing to pass off inferior products to unwitting customers.

So why is overfishing happening? There are a variety of factors driving overfishing that we will delve into here, the bird’s eye view is below.

- Regulation: Regulations are incredibly difficult to enforce even when they are carefully crafted, which they often are not. The worst offenders have little regulations in place and none of these regulations apply in international waters, which are effectively a Wild West.

- Unreported Fishing: Existing regulations force many fisherman to do their fishing “off the books” if they wish to turn a profit. This is especially true in developing nations.

- Mobile Processing: Mobile processing is when fish are processed before even returning to port. They are canned while still out at sea. Canned fish is increasingly taking up the fish consumption market at the expense of fresh fish.

- Subsidies: Anyone familiar with farm subsidies knows that these are actually bad for the production of healthy food. Subsidies for fishing are similar. They don’t generally go to small fisherman whom one would think are most in need, but rather to massive vessels doing fuel-intensive shipping.

What’s more, subsidies encourage overfishing because the money keeps flowing no matter what — the more fish you catch, the more money you get, with no caps influenced by environmental impact fishing regulation.

Indeed, according to the World Wildlife Fund, subsidies drive illegal fishing, which is closely tied with piracy, slavery and human trafficking. The University of British Columbia conducted a study that found that $22 billion (63 percent of all fishing subsidies) went toward subsidies that encourage overfishing.

Of these, the main driver of overfishing is, predictably, government subsidies. So it is worth taking a few minutes to separate that out from the rest of these issues and give it some special attention.

More on Overfishing and Government Subsidies

The subsidies that drive overfishing are highly lucrative: The governments of the world are giving away over $35 billion every year to fishermen. That’s about 20 percent of the value of all the commercially caught fish in the world every year. Subsidies are often directed at reducing the costs for megafishing companies — things like paying for their massive fuel budgets, the gear they need to catch fish, or even the vessels themselves.

This effectively allows for large commercial fishing operations to take over the market or recapitalize at rates significantly below that of the market, disproportionately favoring them over their smaller competitors.

It is this advantage that drives large mega fishing companies into unsustainable fishing practices. The end result of this is not just depleted stocks, but also lower yields due to long-term overfishing, as well as lowered costs of fish at market, which has some advantages for the consumer, but also makes it significantly harder for smaller operations to turn a profit.

Such government subsidies could provide assistance to smaller fishermen, but are generally structured in a way that favors consolidation of the market and efforts counterproductive to conservation efforts.

What Role Do Farmed Fish Play?

Farmed fish is a phenomenon that we take for granted today, but is actually a revolutionary method of bringing fish out of the water and onto our dinner tables. Originally, it was seen as a way of preserving the population of wild fish. The thinking was this: We could eat fish from fish farming while the wild stock replenished itself.

At the same time, communities impacted by overfishing would find new ways to get income in an increasingly difficult market. Third world countries would have their protein needs met in a manner that did not negatively impact the environment. It was considered a big, easy win for the entire world.

The reality, as is often the case, turned out to be a little different. Crowding thousands of fish together in small areas away from their natural habitat turns out to have a number of detrimental effects. Waste products, primarily fish poop, excess food and dead fish, begin to contaminate the areas around fish farms. What’s more, like other factory farms, fish farms require lots of pesticides and drugs thanks to the high concentrations of fish and the parasites and diseases that spread in these kinds of areas.

Predictably, the chemicals used in making farmed fish possible are not contained in the areas where they are initially used. They spread into the surrounding waters and then simply become part of the water of the world, building up over time. In many cases, farmed fish are farmed in areas that are already heavily polluted. This is where the admonition to avoid eating too much fish for fear of contaminants like mercury has come from.

What’s more, the fish that we eat are not the only fish that are living at the fisheries. Often times, the preferred fish of the human consumer are carnivores that must eat lots of other fish to get up to an appropriate size to be part of the market. These fish, known as “reduction fish” or “trash fish” require the same kind of treatment that the larger fish they feed do.

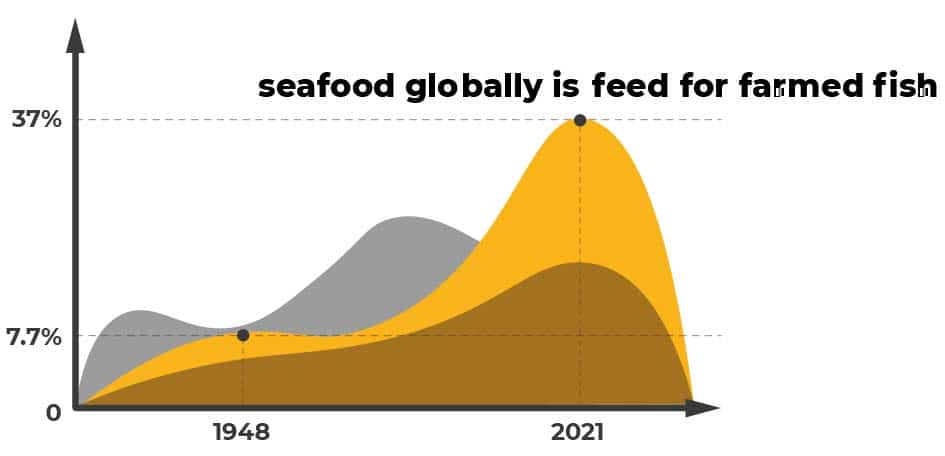

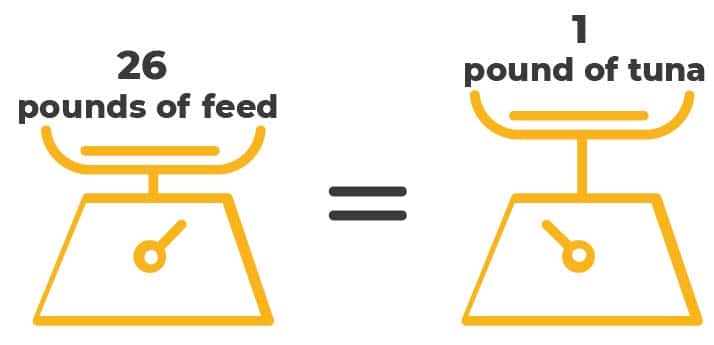

All told, it takes 26 pounds of feed to produce a single pound of tuna, making farmed fishing an incredibly inefficient way of bringing food to market. Indeed, 37 percent of all seafood globally is now fed for farmed fish, up dramatically from 7.7 percent in 1948.

Perhaps worst of all, farmed fish simply do not have the same nutritional value as their wild counterparts, losing almost all of the Omega-3 fatty acids that make fish such a prized part of the modern diet.

Salmon, for example, is only healthy when it is caught in the wild. Farmed salmon is essentially a form of junk food. This is in large part due to the diet that the fish eat in fish farms, which is high in fat and uses soy as a primary source of protein. Toxins at the farms concentrate in the fatty tissue of the salmon. Concentrations of the harmful chemical PCB are found in concentrations eight times higher in farmed fish than traditionally caught wild salmon.

The pesticides, of course, are not used for no reason, but because of the proliferation of pests due to the high concentrations of fish in the fisheries. Sea lice are one example of such pests, which can eat a live salmon down to the bone.

These pests do not stay in the fisheries, but quickly spread to the surrounding waters and infect wild salmon as well as their farmed counterparts. The pests aren’t the only ones escaping: Farmed fish often escape from their habitats and compete with the native fish for resources, becoming an invasive species.

Subsidies vary from one country to another and specific statistics about how much goes to fish farms is generally not forthcoming. But fish farms effectively move the problem of overfishing from the wild oceans and into more enclosed areas. This does not solve any of the problems of overfishing. It merely creates new ones with no less impact on the environment.

Which Countries Are Overfishing?

As stated above, the main offenders with regard to overfishing tend to not be developed Western countries, but countries from the undeveloped world and parts of Asia. Sadly, the United States is the only Western nation that appeared on a “shame list” put out by Pew Charitable Trusts. This is known as the Pacific Six. The other members include Japan, Taiwan, China, South Korea and Indonesia.

The list only refers to overfishing with regard to bluefin tuna, but it provides a snapshot of the face of overfishing internationally. Overfishing facts say that these six countries are fishing 80 percent of the world’s bluefin tuna. These countries took collectively 111,482 metric tons of bluefin tuna out of the waters in 2011 alone.

However, when it comes to harmful subsidies there is a clear leader: China. A University of British Columbia study found that China provided more in the way of harmful subsidies encouraging overfishing than any other country on earth — $7.2 billion in 2018 or 21 percent of all global support. What’s more, subsidies that are more beneficial than harmful dropped by 73 percent.

The negative effects of overfishing are not taking place far away and in very abstract ways. They are causing communities right here in the United States to collapse. In the early 1990s, overfishing of cod caused entire communities in New England to collapse. Once this happens, it is very difficult to reverse. The effects are felt by the marine ecosystem but also by the people whose livelihoods depend on fishing.

Another example of economic instability is the Japanese fish market. Japanese fishermen are able to catch far less fish than they used to, meaning that the Japanese are now eating more imported fish, often from the United States, than ever before. This creates a perverse situation where America exports most of its best salmon to other countries, but consumes some of the worst farmed salmon in the world today.

Just How Bad Is Overfishing?

Surely overfishing can’t be that bad, right? The seas are just filled with tons of fish and it would take us forever to overfish to the point that they began to disappear entirely, right?

Think again. Overfishing is happening at biologically unsustainable levels. Pacific bluefin tuna, the type of fish discussed in the section above, has seen a 97 percent decline in overall population. This is important because the Pacific bluefin tuna is one of the most important predators in the ocean food chain. If it goes extinct the entire aquaculture will be irreparably disturbed.

The first fish that disappear from an ecosystem are larger fish with a longer lifespan and reach reproductive age later in life. These are also the most desirable fish on the open market. When these fish disappear, the destructive fishing operations do not leave the area: They simply move down the food chain to less desirable catches like squid and sardines. This is called “fishing down the web” and it slowly destroys the entire ecosystem removing first the predator fish and then the prey.

There are broader effects on the ecosystem beyond just the fish, effects that resonate throughout the entire Atlantic and Pacific ocean. Many of the smaller fish eat algae that grows on coral reefs. When these fish become overfished, the algae grows uncontrolled and the reefs suffer as a result. That deprives many marine life forms of their natural habitat, creating extreme disruption in the ocean ecosystem.

What Are Some Alternatives to Government-Driven Overfishing?

While there are certainly policy solutions to rampant overfishing, not all solutions will come from governments. For example, there are emerging technological solutions that will make by catching and other forms of waste less prevalent and harmful.

Simple innovations based on existing technologies, such as Fishtek Marine seek to save sea mammals from the nets of commercial fishermen while also increasing profit margins for these companies in a win-win scenario. Their device is small and inexpensive and thus does not present an undue burden to either the large-scale commercial fishing vessels or small fishermen looking to eke out a living in an increasingly difficult market.

We must also recognize that current regulations simply do not work. In one extreme case, governments restricted fishing for certain forms of tuna for three days a year. This did absolutely nothing for the population of tuna, as the big commercial fishing companies simply employed methods to harvest as many fish in three days as they were previously getting in any entire year.

This, in turn, led to a greater amount of bycatch and waste. Because the fishing operations didn’t have the luxury of time to ensure that they were only catching what they sought to catch, their truncated fishing season prized quantity over quality with predictable results.

Quotas, specifically the “individual transferable quota” scheme used by New Zealand and many other countries does not seem to work as intended for a number of reasons. First, these quotas are, as the name might suggest, transferable. This means that little fishermen might consider it a better deal to simply sell their quota to a large commercial fishing operation rather than go to work for themselves and we’re back to square one.

More generally speaking, quotas seem to be a source of waste. Here’s how they work: A fishing operation is given a specific tonnage of fish from a specific species that they can catch. However, not all fish are created equally. So when commercial fishing operations look at their catch and see that some of it is of higher quality than others, they discard the lower-quality fish in favor of higher-quality fish creating large amounts of waste. These discards can sometimes make up 40 percent of the catch.

An alternative to the current system is one that balances the need for fish as a global protein source with a long-term view of the ecosystem, planning for having as many fish tomorrow as there are today and thus, a sustainable model for feeding the world and providing jobs. One way to do this would be to tie subsidies to conservation and sustainability efforts, rather than simply writing checks to large commercial fishing operations to build new boats and buy new equipment. Such a scheme would also prize smaller scale operations over larger ones. A more diversified source of the world’s fish would also be more resilient.

One such alternative is called territorial use rights in fisheries management (TURF). In this case, individual fishermen or collectives of them are provided with long-term rights to fish in a specific area. This means that they have skin in the game. They don’t want to overfish the area because to do so would be to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. So they catch as many fish as is sustainable and no more. They have a vested, long-term interest in making sure that there is no overfishing in the fisheries that have been allotted to them.

Not only does this make sustainable fishing more attractive, it also means that there is less government bureaucracy and red tape involved. Fishermen with TURF are allowed to catch as much as they like. It is assumed that sustainability is baked into the equation because the fishermen with rights want to preserve the fishing not just for the next year, but for the next generation and the one after that. This model has been used successfully by Chile, one of the most economically free countries in the world (more economically free, in fact, than the United States), to prevent overfishing and create sustainability. It is a market-driven model that prizes small producers with skin in the game over massive, transnational conglomerates with none.

Belize, Denmark, and even the United States are other countries that have used TURF, with significantly positive results. While it’s nice to support the little guy over Big Fishing and we certainly support sustainability and conservation efforts, there’s another, perhaps more important and direct reason to support reforms designed to eliminate overfishing: food security. When bluefin tuna, for example, goes extinct, it’s not coming back. That means no more cans of tuna on the shelves of your local supermarket.

That’s a big deal for people in developed, first-world countries, but a much bigger deal in developing countries. When major protein sources are depleted forever, there will be intensified competition for the resources that remain. This also creates unrest in the countries that are less able to compete in a global market due to issues of capital and scale. Even if you’re not concerned with overfishing, overfishing and the problems it creates will soon be on your doorstep unless corrective measures are taken before it’s too late.