You may have heard the quote, "all models are wrong, but some can be useful." It is true. But it is also true that wrong models can be misleading, and some can be lethal. In history, some of these lethal models were fully believed ("let's invade Russia, what could go wrong?), while the lethal consequences of following some current models are still not understood by everyone ("economic growth can continue forever, why not?"). Other models are telling us of the lethal consequences of not following them; it is the case with climate models. There are many kinds of models, but you can't deny that they are important in determining human actions.

Sunday, March 26, 2023

The Worst Model in History: How the Curve was not Flattened

You may have heard the quote, "all models are wrong, but some can be useful." It is true. But it is also true that wrong models can be misleading, and some can be lethal. In history, some of these lethal models were fully believed ("let's invade Russia, what could go wrong?), while the lethal consequences of following some current models are still not understood by everyone ("economic growth can continue forever, why not?"). Other models are telling us of the lethal consequences of not following them; it is the case with climate models. There are many kinds of models, but you can't deny that they are important in determining human actions.

Sunday, January 15, 2023

The Age of Exterminations: How to Kill a Few Billion People

With 8 billion people alive on Earth, it is reasonable to believe that the planet is becoming a little crowded and that life would be better for everyone if there weren't so many people around. But we should not neglect the opposite opinion: that we have resources and technologies sufficient to keep 8 billion people alive and reasonably happy, and perhaps even more. Neither position can be proven, nor disproven. The future will tell us who was right but, in the meantime, it is perfectly legitimate to discuss this subject.

The problem is that we don't have a discussion on population: we have a clash of absolutes. The position that sees overpopulation as a problem has been thoroughly demonized over the past decades and, still today, you cannot even mention the subject without being immediately branded as a would-be exterminator. It happened to Bill Gates, to the Club of Rome, and to many others who dared mention the forbidden term "overpopulation."

The demonization is, of course, a knee-jerk reaction: the people who propose population planning would be simply horrified at being accused of supporting mass exterminations. But note that there is a real problem, here. Exterminations DID happen in the recent past, and they were carried out largely on the basis of a perceived overpopulation problem. During the Nazi era in Germany, the idea that Europe was overpopulated was common and it was widely believed that the "Lebensraum, the "living space," available was insufficient for the German people. The result was a series of exterminations correctly considered the most heinous crimes in human history.

How was that possible? The Germans of that time were the grandfathers of the Germans of today, who are horrified at thinking of what their grandparents did or at least did not oppose. But, for the Germans of those times, killing the Untermenschen, the inferior races, seemed to be the right thing to do, given the vision of the world that was proposed to them and that they had accepted. The Germans fell into a trap called "utilitarianism." It is one of those principles that are so embedded in our way of thinking that we don't even realize that it exists. But it does, and it causes enormous damage.

In principle, utilitarianism wouldn't seem to be such a bad idea. It is a rational calculation of the consequences of taking or not taking a certain action based on generating the maximum good for the maximum number of people. So defined, it looks both sensible and harmless. But that's the theory. What we have is a good illustration of the age-old principle that "in theory, theory and practice are the same thing. In practice, they are not."

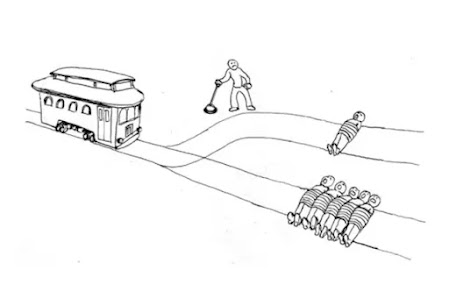

For a good illustration of the problems with utilitarianism in our current society, you can read an excellent post by Simon Sheridan. A typical example of the basic feature of utilitarianism is the diagram in the figure.

In this case, the choice looks obvious. You act on the lever to direct the trolley to the track where it causes a smaller number of victims. Easy? Not at all. The example is misleading because it assumes you know the future with absolute certainty. In the real world, there is no such thing as certainty. There exists such a thing as a "fog of life," akin to the "fog of war." Just like no battle plan survives contact with the enemy, no Gannt chart survives contact with a real calendar. And, if you made a mistake in your evaluation, you may direct the trolley along the wrong path.

Now, of course, Utilitarianism is a big topic and there are numerous sub-variants which are attempts to answer the objections made to the doctrine. Probably the main objection has always been that Utilitarianism implies that killing an innocent is justified if it saves the lives of others. This is one of those classic arguments that always seems confined to university faculties at universities and can usually be counted on to draw the cynical response that it’s “just semantics” and “nobody would ever have to make that decision in real life.”

Well, during the last three years, exactly these kinds of decisions were made. To take just one of the more egregious examples, here in Australia two infants in South Australia needed to be flown interstate for life saving surgery but were denied because the borders were closed due to covid. They died. The justification given, not just by politicians but by everyday people on social media, was the utilitarian one: we couldn’t risk the lives of multiple other people who might get infected with a virus. The greatest good for the greatest number.

(This raises the other main objection to Utilitarianism which is that it must rely on speculative reasoning. We can only predict more people will die based on some model. But we can never know for sure because, despite what many people apparently believe, we are not God and we do not control the future).

The death of those children was a low point even for the corona hysteria and is, in my opinion, one of the lowest points in this nation’s history. Combined with the countless other episodes of people being denied urgent medical care, the elderly residents of nursing homes left without care for days because one of the staff tested positive and all the staff were placed in quarantine, the people unable to be at the side of loved ones who were on their death bed, the daily cases of police brutality, or any of the other innumerable indignities and absurdities, for the first time ever I found myself being ashamed to call myself an Australian.

Sunday, August 28, 2011

The Seneca Effect: why decline is faster than growth

Originally published on "Cassandra's Legacy" on Aug 28 2011

"It would be some consolation for the feebleness of

Don't you stumble, sometimes, into something that seems to make a lot of sense, but you can't say exactly why? For a long time, I had in mind the idea that when things start going bad, they tend to go bad fast. We might call this tendency the "Seneca effect" or the "Seneca cliff," from Lucius Annaeus

Could it be that the Seneca cliff is what we are facing, right now? If that is the case, then we are in trouble. With oil production peaking or set to peak soon, it is hard to think that we are going to see a gentle downward slope of the economy. Rather, we may see a decline so fast that we can only call it "collapse." The symptoms are all there, but how to prove that it is what is really in store for us? It is not enough to quote a Roman philosopher who lived two thousand years ago. We need to understand what factors might lead us to fall much faster than we have been growing so far. For that, we need to make a model and see how the various elements of the economic system may interact with each other to generate collapse.

I have been working on this idea for quite a while and now I think I can make such a model. This is what the rest of this post will be about. We'll see that a Seneca cliff may indeed be part of our future if we keep acting as we have been acting so far (and as we probably will). But let's go into the details.