Afghanistan: a ragged blot of land more or less at the center of the mass of Eurasia and Africa. Over a couple of centuries, it repelled invasions from the largest empires in modern history: Britain, the Soviet Union, and now the United States. It is possible to make an educated guess on what led the United States to invade Afghanistan in 2001 (oil, what else?), but now the time of expansion is over for the Global Empire. We are entering the twilight zone that all empires tend to reach and maintain for a short time before their final collapse.

In 117 AD, Emperor Trajan died after having expanded the Roman Empire to the largest extension it would ever have. It was at the same time a military triumph and an economic disaster. The coffers of the state were nearly empty, the production of the mines was in decline, the army was overstretched and undermanned, unrest was brewing in the provinces. Trajan's successor, Hadrian, did his best to salvage the situation (*). He abandoned the territories that could not be kept, quelled the internal unrest, directed the remaining resources to build fortification at the borders of the Empire. It was a successful strategy and the result was about one century of "Pax Romana." It was the twilight of the Roman Empire, a century or so of relative peace that preceded the final descent.

Empires in history tend to follow similar paths. Not that empires are intelligent, they are nearly pure virtual holobionts and they tend to react to perturbations only by trying to maintain their internal homeostasis. In other words, they have little or no capability to plan for the future. Nevertheless, they are endowed with a certain degree of "swarm intelligence" and they may be able to take the right path by trial and error. Sometimes the process is eased by an intelligent decision-maker at the top. We may attribute the Pax Romana period to the decisions of Hadrian and his successors but, more likely, the Roman Empire simply followed the path it had to follow,

The current empire, the Western (or Global) one may be entering a similar period of retrenching and stabilization: a Pax Americana. I noted this trend when I realized that in the past ten years the Global Empire had not engaged in new major military campaigns. You may argue that 10 years is too short to use to detect meaningful trends. Correct, but there are other elements showing that the Global Empire is retreating and retrenching. For instance, global terrorist attacks and war casualties have been declining for at least five years in a row. And, of course, there has been the announcement that the US is leaving Afghanistan. There will remain "contractors" fighting there, and we can imagine that drones will keep patrolling the sky of Afghanistan, continuing their ongoing spree of senseless killing. But, on the whole, this war is over.

The Afghan campaign was a small military miracle. Just think of the challenges of maintaining an army in a hostile territory, in a remote region not connected to the mainland, and that for 20 years! I think it was never done before in history, not successfully at least. In an earlier Afghan campaign, the British army was not so lucky with only one survivor of an entire army during the retreat from Kabul in 1842. Later, in 1954, the French went through a similar disaster with their base of Dien Bien Phu, in Vietnam. Instead, the Western army is returning from Afghanistan more or less intact.

The Global Empire didn't really lose this war, it just realized that it was impossible to keep fighting it. Indeed, Afghanistan was often termed "Graveyard of Empires" but it never really was. Empires didn't die because they had to leave this remote country, they died for other reasons and, in their agony, they let go this remote and untenable possession of theirs. But, before the Western Empire disappears for good, we may perhaps be able to enjoy a period of Pax Americana, just as the

Romans did after that Hadrian became emperor.

With the Afghan campaign over, we may ask ourselves why did the empire engage in it. Wars, like all human enterprises, are generated by those virtual entities we call memes. These are patterns of ideas that dominate the human mind, it was Daniel Dennett who said that human beings are meme-infested apes. So, the general interpretation of this story is related to a meme that appeared in the aftermath of the attacks of Sept 11, 2001, supposed to have been masterminded by an evil sheik named Osama bin Laden who had a hidden military base in a complex of caves in North Afghanistan. The connection of this meme with reality was always flimsy, to say the least, not better than that of "weapons of mass destruction" in Iraq. And, indeed, no traces of Osama or of an important military base hiding terrorists in Afghanistan were ever found. But the power of memes does not depend on their link with reality.

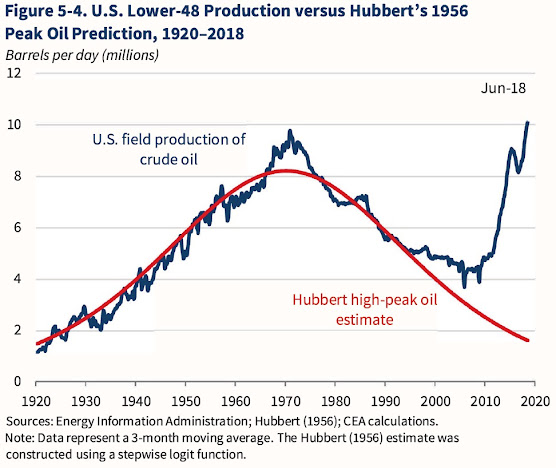

But there probably was a much more powerful meme that led to the US invasion of Afghanistan. It had nothing to do with a bearded sheik hiding in a cave. Rather, it was about the issue that generated most of the recent wars: crude oil.

Of course, Afghanistan has no oil, and this much was known. But in the 1990s the oil reserves of the Caspian region, adjacent to Afghanistan, had been the object of a game of aggrandizing that led to exaggerating their extent at least of an order of magnitude. As a result, the US may have been looking for the dark brown meme of "A New Saudi Arabia" that involved taking control of Afghanistan.

Back in 2004, I wrote the story of the development of this meme in a post in Italian.

Below, I updated and condensed it into a version in English. At that

time, I couldn't imagine that the Afghan campaign would go on for nearly

two decades more, but memes are unstoppable when they take hold of

human minds.

Nevertheless, I don't think there is a rational explanation for these events. Just like what Tolstoy said about the French invasion of Russia, in 1812, the Afghan war happened "because it had to happen." And if it is over, now, it is because it had to be.

My interpretation is that during the past 10 years or so, we created a Web creature endowed with swarm intelligence that is taking over humankind's memesphere. Maybe I am wrong and, of course, I have no proof that this is the case. But I have the strong impression that the great games that empires play may not be anymore in the hands of those psychopaths who call themselves "emperors". And the future will be what it has to be.

See also this post by Tom Engelhart that makes very similar observations on the withdrawal phase of the American Empire.

(*) About Hadrian, you probably know the book titled "Memoirs of Hadrian" by Marguerite Yourcenar. It is an excellent book in many respects, first of all as a literary masterpiece, but also because it clearly understand and describes the situation of the Roman Empire after that Trajan had nearly destroyed by overextending its borders. But, despite Yourcenar's flattering portrait, Hadrian was no Mr. Nice Emperor. He was ruthless against his political enemies and against all opposition. In 136 AD, he destroyed what was left of Jerusalem after the siece of 70 AD, attempting to erase even the name of the city that was rebuilt under the name of Aelia Capitolina.

THE CASPIAN OIL FEVER.

By Ugo Bardi

A longer version of this story was published in Italian on the “ASPOITALIA” website in August 2004.

The Caspian oil fever started in the late 1990s, when it became fashionable in the West to speak about the "immense reserves" of crude oil that could be found in the area around the Caspian Sea. So rich was this region supposed to be that it would be possible to turn it into a "New Saudi Arabia" (sometimes "A New Persian Gulf"). But the story had started much earlier than that.

The Caspian oil fever started in the late 1990s, when it became fashionable in the West to speak about the "immense reserves" of crude oil that could be found in the area around the Caspian Sea. So rich was this region supposed to be that it would be possible to turn it into a "New Saudi Arabia" (sometimes "A New Persian Gulf"). But the story had started much earlier than that.

Already in mid 19th century, the first oil wells were dug near Baku in the Azerbaijan region. In 1873, Robert Nobel, the brother of Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, led an expedition southward from St. Petersburg. He found in Baku, on the Caspian shore, an already operating oil industry. Nobel invested in this industry, developing it considerably. At the end of the nineteenth

century, Baku was the largest oil-producing area in the world, even

surpassing the American oil industry of the time.

At that time, oil was mainly turned into kerosene and then used as fuel for oil lamps. Our great-grandparents' lamps in Western Europe were almost certainly lit with oil supplied by the Caucasus mining industry (the advertising for kerosene, in the figure, seems to come from Latvia, but the oil surely came from the Caucasus). With the development of the internal combustion engine, in the early twentieth century, oil began to be used more and more as a fuel. The

strategic value of the Caucasus fields was already important in the

First World War, when the shortage of oil was one of the factors that caused the defeat of the Central Empires. But it became evident with the

Second World War which was, in many ways, the first, true "war for

oil."

When

the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, one of their main strategic objectives was the oil fields of the Caucasus. In the offensives of 1941 and 1942, the Germans tried to advance towards the Caucasus, but the battle of Stalingrad put an end to their attempts. That was the turning point of the war. Had the Germans succeeded in taking hold of the Caucasus, history could have been very different (and maybe you would be reading this post in German).

After the Second World War, the Soviet Union began to find difficulties with expanding the production of oil from the Caucasus. From the 1950s onward, the reserves of the Urals, the Volga region, and eastern Siberia were the main target for development. These reserves made the Soviet Union the largest oil producer in the world until about 1990.

By the end of the 1980s, the Soviet oil production began to show signs of difficulty and, in 1991 the production peak was reached, with decline starting afterward. At the same time, there arrived the collapse of the Soviet Union itself. There are many interpretations of the reason for this collapse, but it is possible that the decline of oil production was not a consequence but

the main cause of the collapse of the Soviet Empire, the political structure that was created to exploit it.

This story tells us a lot about the situation in the Caucasus after the fall of the Soviet Union. Since the oil fields had been exploited for over a century, we should not be surprised if they were depleted and declining. But the Western oil industry looked with some interest at the Caspian area, believing that their superior technology could extract oil not accessible to the Soviets. As early as in 1985, Harry E. Cook, of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) began exploring Central Asia for possible new oil reserves. Later, under Cook's leadership, a consortium called “USGS-Kazakhstan-Kyrgyzstan Oil Industry project” was formed which included ENI/AGIP as well as BG, BP, ExxonMobil, Inpex, Phillips, Royal Dutch Shell, Statoil, TotalFinaElf, and several ex-Soviet research institutes.

The first contract with the consortium to export Caspian oil to the West was signed in 1994. It turned out to be a difficult task because of the need to carry equipment to a remote geographical location, not accessible by sea. It was necessary to wait until 1999 before it became possible to export Caspian oil through the Baku-Novorossiirsk pipeline, which ends on the Black Sea. From there, the oil could be shipped worldwide.

But in the 1990s a virtual kind of oil that existed only in the minds of people had also appeared. The story started in 1997 with the publication of a U.S. Department of State Report: (U.S. Department of State, Caspian Region Energy Development Report, April 1997). (a version of the report can be found

at this link).

In the report, the following table could be found:

It

seems that the data of the report were derived from Cook's work

stating that the Kashagan field could hold up to 50 billion barrels, a

value

that had been further inflated here to 85 billion, so that the total for Kazakhstan arrived at a whopping 95 billion barrels. The total amount of "possible" reserves in the area was estimated at 178 billion barrels of oil. It

is not clear what the authors meant by the term "possible oil." In the practice of reporting oil reserves, the term "possible reserves" is normally coupled with a probabilistic estimate, usually 5%. So, what the table said was that there was "a 5% chance of finding

163 billion barrels"

Such a statistical estimate was incomprehensible to the average politician and these data were badly misunderstood. The

first political exponent to speak publicly about the discovery of new,

"immense reserves" of the Caspian Sea seems to have been the US Deputy

Secretary of State Strobe Talbott

in 1997. Talbot used on that occasion, perhaps for the first time, the phrase "reserves up to two hundred billion barrels of oil."

Talbot had rounded up the "possible reserves" to 200

billion barrels. Other people spoke of 250 billion, and in some case, you heard of 300 billion barrels. If these estimates were true, it would have meant that the Caspian could have increased the global oil reserves of about by 20%, not a trifle! But the main effect

of these new reserves would have been to drastically break the quasi-monopoly

of OPEC countries and the Middle East on oil and completely changing the geopolitical framework of world oil production. This was the origin of the enthusiasm about "A New Saudi Arabia" that could exist in the Caspian region.

As the exploration proceeded, the available data was further processed.

In 2000, the USGS released a report signed by Thomas Ahlbrandt that arrived at an estimate of world reserves at least 50% higher than all previous estimates. This report was

criticized by many experts and contradicted by the trend of subsequent

finds, but it was another of the elements that led to the myth of

the Caspian Sea as a new oil El Dorado.

The "200 billion barrels" story began to generate doubts from the moment it appeared. Already in 1997, a report by Laurent Ruseckas to the United States congress scaled down the estimates by speaking of a "possible maximum" of

145 billion barrels, a value that had to be taken as an unlikely

extreme, with a reasonable maximum value of around 70 billion barrels.

Ruseckas also pointed out that someone was getting too enthusiastic.

Skepticism rapidly began to spread. A 1998 article in Time magazine stated that if

these estimates were correct, the Caspian region could contain "the

equivalent of 400 giant fields," yet there are only 370 giant fields in

the world (Robin Knight, “Is The Caspian An Oil El Dorado? Time Magazine, June 29, 1998,

Vol. 151 No.26). In 1999, a report presented to the SPD group in the German parliament (1999 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Washington Office 1155 15th Street, NW Suite 1100 Washington, A.D 20005)

was titled, significantly, "No longer the 'Great Game' in the Caspian".

In one section of this report, Friedemann Muller stated that:

"The often reported figure - preferably by politicians of a certain age -

200 billion barrels is a figment of the imagination ”. The

issue of inflated reserves also appeared in the popular press, for

example, in a November 11, 2001, Toronto "NOW" article, Damien Cave

described the Caspian estimates of 200 billion barrels as "insanely

optimistic, at least in the next twenty years."

The

real world started intruding into the fantasy of politicians when the OKIOC consortium (ENI,

BP, BG, ExxonMobil, Inpex, Phillips, Shell, Statoil, and TotalFinaElf) started actually drilling at the bottom of the Caspian sea. Apparently, the results were not impressive, since the consortium began to fall apart after the first exploratory drilling. By 2003 ExxonMobil, Statoil, BP, and BG

had left. Agip remained and became the main operator of the consortium.

In April 2002, Gian Maria Gros-Pietro, then the president of ENI,

speaking at the Eurasian Economic Summit in Almaty, Kazakhstan, declared that the entire Caspian could contain only 7-8 billion barrels. Others have estimated up to 13

billion barrels for the Kashagan field alone. For the whole area around the Caspian Sea, it is possible to speak of amounts between 30 and 50 billion barrels.

These reserves are not negligible but available only at high costs and certainly not a new Saudi Arabia.

By the early 2000s, the situation was reasonably clear, at least in the eyes of the experts. Colin Campbell, the founder of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil (ASPO) summed it up like this in a private communication to the author of these notes.

“ There

were rumors that the area contained over 200 Gb [billion barrels] of

oil (I think those rumors came from the US Geological Survey), but the

results after ten years of construction have been disappointing. As

early as 1979, the Soviets had found the Tengiz field on the mainland in

Kazakhstan. It contains about 6 billion barrels of oil in a limestone reef at a depth of about 4500 m.This oil,

however, contains up to 16% sulfur, which was too much even for Soviet

steel, so they chose to not to exploit the field. After the fall of the

Soviet Union, Chevron, and other American companies arrived and managed

to extract that oil, but with many difficulties and at high economic and

environmental costs.

Later,

in a series of surveys made on the bottom of the Caspian Sea, a huge structure was found at about 4000 meters deep that in many ways resembled that of Tengiz. This area (Kashagan) also had geological features similar to those of the giant Al Ghawar field in Saudi Arabia. Had it been full, it could have actually held 100 billion barrels or perhaps more and competed with Saudi wells.

At that point, an American businessman, Jack Grynberg, put together a

large consortium of oil companies that included BP, Statoil, Total,

Agip, Phillips, British Gas, and others. This consortium set out to exploit the deposits thought to exist in this facility.

Exploratory

drilling has been enormously difficult. The field was offshore, so it was difficult and complex to transport equipment to the area. In addition, those waters were a breeding ground for the sturgeons that produce Russian caviar. Finally, the winter climate of the area is harsh with ice formations on the surface of the water and very strong winds.

Eventually, at a cost of $ 400 million, the consortium managed to drill a

4,500-meter deep well in the easternmost area of the facility. A

deadly silence followed, followed shortly after by BP and Statoil's withdrawal from the company. British Gas announced in a report that the field could contain between 9 and 15 billion barrels. The reason is that,- unlike Al Ghawar - the field is very fragmented with the fields separated by low quality rocks. It is an interesting field and it is certain that further reserves will be found, but it is certainly not capable of having any significant effect on world supplies. There is a

lot of gas nearby, but the transportation difficulties are immense. "

Nevertheless, the two worlds, that of the politicians and that of the experts had decoupled from each other and plenty of people were still believing in the existence of "200 billion barrels" in the Caspian region. From the left, the "immense reserves" of the Caspian were cited. as proof of evil Western imperialism. From the right, there was a clamor to get their hands on that bonanza as soon as possible. As

an example, we can cite

the speech that US Senator Conrad Burns, who had traveled to Kazakhstan himself, gave to the Heritage

Foundation, on March 19, 2003

"Every dollar we spend of Middle East oil, we are really dealing in rogue

oil. Money that goes to build weapons of mass destruction and also the

fuel those terrorist groups that need money to operate around the

world," Burns said. "We don't have to look to the Middle East, because

the reserves in the Caspian Basin could be as large as what is in the

Middle East"

and:

Internationally,

our country is ignoring the opportunities that exist in Russia and in the Caspian Sea basin. In the Caspian Sea area, reserves of up to 33

billion barrels have been found, a potential greater than that of the United States and the double that of the North Sea. Estimates speak of an additional 233 billion barrels of reserves in the Caspian. These reserves could represent up to 25% of the world's proven reserves. Russia may have even more abundant reserves.

These numbers are all wrong. For one thing, the North Sea reserves are estimated at around 50 billion barrels, and 33 is certainly not double 50. As for the "255 billion barrels", added to the other 33 make a total of 288 billion of barrels,

which is out of the grace of God. But, clearly, Burns was not the only American politician who thought in these terms. And much of what happened after the 9/11 attacks of 2001 can be explained as an attempt by the US government to take direct control of the strategic oil fields of the Middle East and of Central Asia. Not for nothing Conrad Burns was a convinced supporter also of the invasion of Iraq.

In the end, it doesn't seem to be paranoid to think that the United States attacked

Afghanistan in 2001 in order to clear the field at the passage of an oil pipeline from the Caspian that would reach the Indian Ocean passing through Pakistan. A grand dream, if ever there was one. But there were no "immense reserves" in the Caucasus and, therefore, no need for a pipeline to transport them. And reality, as usual, eventually took over.