Imagine a university campus seen from a drone. Zoom down to one of the buildings. There, imagine a human figure running out of it, screaming while holding his head with his hands. Imagine him running and running, dashing out of the campus gate, and then disappearing in the fog, still running at full speed and screaming. That was me, leaving the University of Florence forever.

I still had some time before mandatory retirement, but I couldn't take it anymore. The Covid regulations were the killing blow to an institution that had already become a monstrosity. And I left my university this March, after 40 years of employment.

To explain why I quit my job, I should tell you how it is to work at a mid-level university. Of course, the definition of "mid-level" depends on the parameters you use, but the University of Florence is normally ranked somewhere within the first 500 universities worldwide. This is not so bad considering that there are tens of thousands of institutions in the world that label themselves as "universities." But it is nothing to be enthusiastic about.

Is it a bad thing to work at a mid-level university? Not necessarily. I have experience working in top-level ones (just to name one, I was a post-doc at Berkeley) and I know that in a higher-level university I could have had a higher salary, more support, and more chances to attract financing. But also more stress, more pressure, and more control.

So, I don't envy the life of the colleagues who have been running the rat race. The way scientific research is organized nowadays implies discouraging interdisciplinary and innovative research. Actually, not just discouraging -- the whole system aims at carpet bombing with napalm everything and everyone who tries to do something new. If you work in a top-level university, you are supposed to perform. And performing means acting strictly according to the rules. But, in a mid-level university, you are not so heavily pressured, and that gives you a chance to explore new ideas and move to new fields.

To be clear, this is not a hymn to mediocrity. Being in a mid-level university does not mean you can't do top-level work. By all means, you can, and you should. True, you don't have the same kind of financial support you can have at the top scientific watering holes. From the periphery of the Global Empire, you just can't access the old boy networks that manage scientific funds. But you can compensate with creativity and flexibility. As an example, the Chemistry Department of the University of Florence, where I was working, scores consistently as the best department of chemistry in Italy, and it is at the top level worldwide in several fields. It has done so well, I think, because researchers were left mostly free to organize their work and to pursue the lines they thought were most rewarding.

So, what led me to run away screaming from a structure that I considered not so bad? In one word: bureaucracy. It has been a slow trend but, year after year, bureaucrats had been penetrating more and more into the organization of research. They were the administrators, but also colleagues who gradually transmogrified themselves from researchers into paper-shufflers. As a result, we were asked to list our "products" (the name that bureaucrats give to scientific papers), to declare our bibliometric indices, and to fill out plenty of forms reporting on our performance. Also, bureaucrats saw the university as a cash cow and they made sure to take a larger and larger toll on the university budget. The number of administrative employees kept increasing and the salary of a top bureaucrat became higher than that of a senior faculty member. Eventually, the administrative director could fire the rector (not officially, but it happened in Florence). All that is not just a problem with the University of Florence, it is the same in all the universities of the world.

The final nail in the coffin was the pandemic. It gave bureaucrats the possibility of scoring an epochal victory on faculty members. Truly, it was not just a victory, it was the complete annihilation of the enemy. Before the pandemic, the university was still a relatively open institution, where I was free to go anywhere on our campus and to receive anyone in my room. I could invite anyone to give a talk, from Italy or abroad. I could invite researchers from anywhere to work in my group. My students could visit me at any time, and the door of my office was always open.

All that was vaporized by the regulations: a garden of delights for bureaucrats. The new rules were typically not based on verifiable data, but they were always strict, detailed, and rigid. Social distancing, face masks, sanitizing everything, even delicate and expensive instruments that didn't benefit from being sprayed with solvents. If I wanted to receive someone in my office, I had to ask permission from the director of the department at least 24 hours in advance, and explain who was the person I wanted to meet, why I wanted to meet him/her, and for how long. To enter our department, we were tested, sanitized, masked, QR-ed, and our body temperature measured. You see in the picture one of the infernal machines that appeared at the entrances of all the university buildings. It was correctly referred to as a "totem" -- an offering to evil deities. And no more socializing with your colleagues and students. No more than two persons per room, eating or drinking on the premises was strictly forbidden. Even the coffee machines in the corridors disappeared. (recently, they reappeared, but the surrounding conviviality didn't return: you have to keep at a certain distance, stay in line, follow the arrows painted on the floor).

But that was nothing in comparison to what happened to teaching. For most people, a chemistry class is like a session with a dentist: you don't expect it to be pleasant, and you want it to be over as soon as possible. Yet, before the pandemic, lessons could be interactive, lively, and -- as much as possible -- interesting. You dealt with real human beings sitting in front of you, and you could discuss matters even not strictly related to the subject of your class. I had my students doing hands-on experiments, playing operational games, I had them learn how to make fire with a flint and once I had them sing a piece of polyphonic music. Maybe it was not chemistry, but they enjoyed that.

All that disappeared in a whooshing sound with the pandemic. Suddenly, the students were turned from human beings into stamp-size images on a screen. And that was when they agreed to show their faces, you couldn't force them to. You had no idea if they were listening to you or playing games, or watching movies on their screens (If they were there at all). Even worse was the "mixed" mode that appeared in 2021. A few masked students could reserve seats in the classroom, and each occupied seat was spaced from the next one by two unoccupied ones (a rule surely based on solid data). The majority of the students would remain in remote mode, and you had exactly zero interaction with them -- you had no idea of who was listening to you if any did. A colleague of mine in another Italian university was suspended for six months from teaching as a punishment for having told her students on a hot day that they could lower their masks if they wanted.

What was most shocking is how my colleagues took this bureaucratic storm. No protests, no questions, no discussions. I mean, we are supposed to be scientists: someone could have asked questions about the rules: what proof do you have that washing one's hands with solvents has any useful effect? On which basis were we forbidden to touch a piece of paper previously handed by a student? What proof do you have that staying at 1 meter from each other prevents infection?

But no rule was criticized, no matter how quixotic. Administrators, and even many faculty members, were enthusiastic about the new rules. As in the Milgram experiment, they were given a chance to abuse their colleagues by taking formal or informal roles of guardians of the heavenly palace, and they took it gleefully. Before the pandemic, the lady at the reception desk was always smiling and kind. Afterward, she became something like a prison guard, even though she wasn't wearing a uniform. I can tell you that I have been a guest researcher at the Academy of Sciences in Moscow, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, and the guards at the entrance were more friendly.

I don't remember what exactly was the last straw, but at some moment I found myself packing. Books, papers, pictures, equipment, and various stuff accumulated in forty years. Of my books, I donated some 350 of them to our library. The librarians were moderately happy to receive that gift, but they (and I) are perfectly aware that our students are becoming unable to understand English, so most of these books will just collect dust until they will be consumed in some fire at the end of our civilization. But so is life. In the picture, you can see me in the inner caverns of the library, with the books I laboriously carried there.

And now what? Initially, I was a little afraid. Mandatory retirement in Europe is a terrible experience for the people who are forced to retire while still active and perfectly able to do their job. But, in my case, I have to thank the small peduncled creature that made me hate my job. I can tell you that I am not feeling anything like the "retirement shock" that killed some of my colleagues. No kidding: they fell sick and died shortly after retiring. And they were in perfect health before.

So, right now, I am in perfect shape, and perfectly happy. It is over with boring classes, filling forms, attending meetings, be part of committees, and more useless ways to spend one's time. God, you really love me!!! I can spend all my time doing the things I love to do. Like spending an inordinate amount of time writing posts on the "Seneca Effect" blog. But not just that. Science can be a lot of fun when you are not pressured by review committees and funding agencies (see below). And I am also working on some weird things I won't tell you anything about.

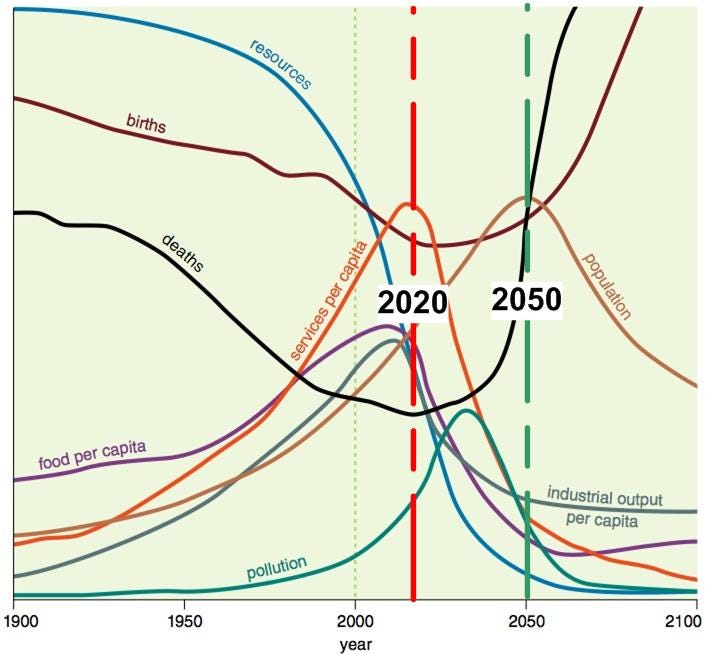

Hard times seem to be coming, but we have to accept what the universe has prepared for us. And so, the future is waiting for us. Who knows what expects us once we'll be there?

_________________________________

Fun with science

Science used to be something done just for the sake of learning new things, and I think it can still be done in this spirit. Check our paper (with

Ilaria Perissi) on the

"6th law of stupidity" and you'll see what I mean. Of course, the reviewers were horrified by a paper that was not boring. But, eventually, we overcame their criticism with good arguments and persistence. We (with Ilaria and others) also published

a paper on dragonology (not exactly the science of dragons, but the dragons of science).

Another paper written with Ilaria was inspired by Herman Melville's "Moby Dick" novel. We described how the cycle of whaling of 19th century is an example of the overexploitation of natural resources. It is a dynamical cycle that we simulated using a boardgame for educational purposes. The paper is under review, for the time being, you can take a look at an earlier version called

the "Oil Game."

We are now (again, with Ilaria) world-renown experts on mousetraps as related to nuclear explosions (the paper is

on Arxiv, we have a full paper under review). In the picture, you see a mouse I captured recently. Don't worry, the little fella was not mistreated. It was released, alive and well, in a place where I am sure it can find food.

You think all this is not serious science? Well, if you want serious science, here is serious science, at least in terms of words full of sound and fury: "The Role of Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROI) in Complex Adaptive Systems" (Perissi, Lavacchi, and Bardi). Serious stuff, but it was fun to study this subject, even though we wrote the paper in a rather boring form, full of mathematical formulas.

By the way, if you dabble with EROI-related things, you know that the "Hubbert Curve" is the result of the declining EROI of oil extraction. And you may have asked yourself (but never dared to ask) what is the value of the EROI at "peak oil"? Well, you won't find that datum anywhere, but we (again, I and Ilaria) know! The paper is being prepared, and the mystery will be revealed soon. And there is more in the pipeline, including a long paper on the concept of "

social holobionts" -- halfway through it, right now. Onward, fellow holobionts!