When an apple has ripened and falls, why does it fall? Because of its attraction to the earth, because its stalk withers, because it is dried by the sun, because it grows heavier, because the wind shakes it, or because the boy standing below wants to eat it? Nothing is the cause. All this is only the coincidence of conditions in which all vital organic and elemental events occur. (Lev Tolstoy, "War and Peace")

Excuse me if I return to the Afghanistan story. I don't claim to be an expert in international politics, but if what happened is the result of the actions of "experts", then it is safe to say that it is better to ignore them and look for our own explanations.

So, I proposed an interpretation of the Afghan disaster in a recent post of mine, together with a report on the story of how the oil reserves of the region of the Caspian Sea were enormously overestimated starting with the 1980s. Some people understood my views as meaning that I proposed that crude oil was the cause of the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. No, I didn't mean that. Not any more than the story of the "butterfly effect" means that a butterfly can actually cause a hurricane -- of course it would make no sense.

What I am saying is a completely different concept: a butterfly (or dreams of immense oil reserves) are just triggers for events that have a certain potential to happen. Take a temperature difference between the water surface and the air and a hurricane can happen: it is a thermodynamic potential. Take a military industry that makes money on war, and a war can take place: it is a financial potential. A hurricane and a military lobby are not so different in terms of being complex adaptive systems.

So, let me summarize my opinion on the Afghanistan conflict. I think that these 20 years of madness have been the result of a meme gone viral in the mid-1980s that triggered an event that happened because there were the conditions to make it happen: the invasion of Afghanistan.

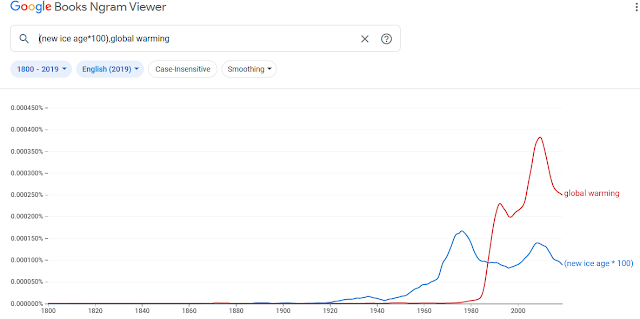

It all started in the mid-1980s, when an American geologist, Harry Cook, came back from Kazakhstan with a wildly exaggerated estimate of the oil reserves of the Caspian area. He probably understood the uncertainty of his numbers, but statistical thinking is not a characteristic of American politicians. Cook's numbers were taken at face value and further inflated to give rise to the "New Saudi Arabia" meme: resources so abundant that they would have led to a new era of oil prosperity. At this point, the question became about how to get the (hypothetical) Caspian bonanza.

Even before the presence of these reserves was proven (or disproved), in the mid-1990s negotiations started for a pipeline going from the oil fields of Kazakhstan to the Indian Ocean, going through Afghanistan. That involved negotiating with the Taleban and with a Saudi Arabian oil tycoon named Osama Bin Laden. Something went wrong and the negotiations collapsed in 1998. Then, there came the 9/11 attacks and the invasion of Afghanistan. It was only in the mid-2000s that actual drilling in the Caspian area laid to rest the myth of the New Saudi Arabia. But the occupation of Afghanistan was already a fact.

Does this story explain 20 years of US occupation of Afghanistan at a cost of 2 trillion dollars and the humiliating defeat we see now? No, if you think in terms of cause and effect. Yes, if you think of it in terms of a diffuse meme in the minds of the decision-makers. I can't imagine that there ever was someone masterminding the whole folly. But there was this meme about those immense oil reserves north of Afghanistan that influenced all the decisions made at all levels. Memes are an incredibly powerful force.

To explain my point better, I can cite Lev Tolstoy's description of what led millions of Western Europeans to invade Russia in 1812, a decision as foolish as that of invading Afghanistan in 2001. Tolstoy says that "it happened because it had to happen."

Tolstoy means that it was the result of a series of macro- and micro-decisions taken by all the actors in the story, including the simple soldiers who decided to enlist with Napoleon. But there was no plan, no grand strategy, no clear objectives directing the invasion. Even Napoleon himself was just one of the cogs of the immense machine that generated the disaster. "A king is history's slave," says Tolstoy.

Tolstoy's had an incredibly advanced way of thinking: what he wrote could have been written by a modern system scientist. You see it in nearly every paragraph of this excerpt from "War and Peace." An amazing insight on the reason for the folly of human actions at the level of what Tolstoy calls the "hive," that today we would call the "memesphere."

From "War and Peace" - Lev Tolstoy Book 9, chapter 1

On the twelfth of June, 1812, the forces of Western Europe crossed the Russian frontier and war began, that is, an event took place opposed to human reason and to human nature. Millions of men perpetrated against one another such innumerable crimes, frauds, treacheries, thefts, forgeries, issues of false money, burglaries, incendiarisms, and murders as in whole centuries are not recorded in the annals of all the law courts of the world, but which those who committed them did not at the time regard as being crimes.

What produced this extraordinary occurrence? What were its causes? The historians tell us with naive assurance that its causes were the wrongs inflicted on the Duke of Oldenburg, the nonobservance of the Continental System, the ambition of Napoleon, the firmness of Alexander, the mistakes of the diplomatists, and so on. Consequently, it would only have been necessary for Metternich, Rumyantsev, or Talleyrand, between a levee and an evening party, to have taken proper pains and written a more adroit note, or for Napoleon to have written to Alexander: ‘My respected Brother, I consent to restore the duchy to the Duke of Oldenburg’- and there would have been no war.

We can understand that the matter seemed like that to contemporaries. It naturally seemed to Napoleon that the war was caused by England’s intrigues (as in fact he said on the island of St. Helena). It naturally seemed to members of the English Parliament that the cause of the war was Napoleon’s ambition; to the Duke of Oldenburg, that the cause of the war was the violence done to him; to businessmen that the cause of the way was the Continental System which was ruining Europe; to the generals and old soldiers that the chief reason for the war was the necessity of giving them employment; to the legitimists of that day that it was the need of re-establishing les bons principes, and to the diplomatists of that time that it all resulted from the fact that the alliance between Russia and Austria in 1809 had not been sufficiently well concealed from Napoleon, and from the awkward wording of Memorandum No. 178.

It is natural that these and a countless and infinite quantity of other reasons, the number depending on the endless diversity of points of view, presented themselves to the men of that day; but to us, to posterity who view the thing that happened in all its magnitude and perceive its plain and terrible meaning, these causes seem insufficient. To us it is incomprehensible that millions of Christian men killed and tortured each other either because Napoleon was ambitious or Alexander was firm, or because England’s policy was astute or the Duke of Oldenburg wronged. We cannot grasp what connection such circumstances have with the actual fact of slaughter and violence: why because the Duke was wronged, thousands of men from the other side of Europe killed and ruined the people of Smolensk and Moscow and were killed by them.

To us, their descendants, who are not historians and are not carried away by the process of research and can therefore regard the event with unclouded common sense, an incalculable number of causes present themselves. The deeper we delve in search of these causes the more of them we find; and each separate cause or whole series of causes appears to us equally valid in itself and equally false by its insignificance compared to the magnitude of the events, and by its impotence- apart from the cooperation of all the other coincident causes- to occasion the event. To us, the wish or objection of this or that French corporal to serve a second term appears as much a cause as Napoleon’s refusal to withdraw his troops beyond the Vistula and to restore the duchy of Oldenburg; for had he not wished to serve, and had a second, a third, and a thousandth corporal and private also refused, there would have been so many less men in Napoleon’s army and the war could not have occurred.

Had Napoleon not taken offense at the demand that he should withdraw beyond the Vistula, and not ordered his troops to advance, there would have been no war; but had all his sergeants objected to serving a second term then also there could have been no war. Nor could there have been a war had there been no English intrigues and no Duke of Oldenburg, and had Alexander not felt insulted, and had there not been an autocratic government in Russia, or a Revolution in France and a subsequent dictatorship and Empire, or all the things that produced the French Revolution, and so on. Without each of these causes nothing could have happened. So all these causes- myriads of causes- coincided to bring it about. And so there was no one cause for that occurrence, but it had to occur because it had to. Millions of men, renouncing their human feelings and reason, had to go from west to east to slay their fellows, just as some centuries previously hordes of men had come from the east to the west, slaying their fellows.

The actions of Napoleon and Alexander, on whose words the event seemed to hang, were as little voluntary as the actions of any soldier who was drawn into the campaign by lot or by conscription. This could not be otherwise, for in order that the will of Napoleon and Alexander (on whom the event seemed to depend) should be carried out, the concurrence of innumerable circumstances was needed without any one of which the event could not have taken place. It was necessary that millions of men in whose hands lay the real power- the soldiers who fired, or transported provisions and guns- should consent to carry out the will of these weak individuals, and should have been induced to do so by an infinite number of diverse and complex causes. We are forced to fall back on fatalism as an explanation of irrational events (that is to say, events the reasonableness of which we do not understand). The more we try to explain such events in history reasonably, the more unreasonable and incomprehensible do they become to us.

Each man lives for himself, using his freedom to attain his personal aims, and feels with his whole being that he can now do or abstain from doing this or that action; but as soon as he has done it, that action performed at a certain moment in time becomes irrevocable and belongs to history, in which it has not a free but a predestined significance. There are two sides to the life of every man, his individual life, which is the more free the more abstract its interests, and his elemental hive life in which he inevitably obeys laws laid down for him. Man lives consciously for himself, but is an unconscious instrument in the attainment of the historic, universal, aims of humanity. A deed done is irrevocable, and its result coinciding in time with the actions of millions of other men assumes an historic significance. The higher a man stands on the social ladder, the more people he is connected with and the more power he has over others, the more evident is the predestination and inevitability of his every action.

‘The king’s heart is in the hands of the Lord.’

A king is history’s slave.

History, that is, the unconscious, general, hive life of mankind, uses every moment of the life of kings as a tool for its own purposes. Though Napoleon at that time, in 1812, was more convinced than ever that it depended on him, verser (ou ne pas verser) le sang de ses peuples*- as Alexander expressed it in the last letter he wrote him- he had never been so much in the grip of inevitable laws, which compelled him, while thinking that he was acting on his own volition, to perform for the hive life- that is to say, for history- whatever had to be performed.

The people of the west moved eastwards to slay their fellow men, and by the law of coincidence thousands of minute causes fitted in and co-ordinated to produce that movement and war: reproaches for the nonobservance of the Continental System, the Duke of Oldenburg’s wrongs, the movement of troops into Prussia- undertaken (as it seemed to Napoleon) only for the purpose of securing an armed peace, the French Emperor’s love and habit of war coinciding with his people’s inclinations, allurement by the grandeur of the preparations, and the expenditure on those preparations and the need of obtaining advantages to compensate for that expenditure, the intoxicating honors he received in Dresden, the diplomatic negotiations which, in the opinion of contemporaries, were carried on with a sincere desire to attain peace, but which only wounded the self-love of both sides, and millions and millions of other causes that adapted themselves to the event that was happening or coincided with it.

When an apple has ripened and falls, why does it fall? Because of its attraction to the earth, because its stalk withers, because it is dried by the sun, because it grows heavier, because the wind shakes it, or because the boy standing below wants to eat it? Nothing is the cause. All this is only the coincidence of conditions in which all vital organic and elemental events occur. And the botanist who finds that the apple falls because the cellular tissue decays and so forth is equally right with the child who stands under the tree and says the apple fell because he wanted to eat it and prayed for it.

Equally right or wrong is he who says that Napoleon went to Moscow because he wanted to, and perished because Alexander desired his destruction, and he who says that an undermined hill weighing a million tons fell because the last navvy struck it for the last time with his mattock. In historic events the so-called great men are labels giving names to events, and like labels they have but the smallest connection with the event itself. Every act of theirs, which appears to them an act of their own will, is in an historical sense involuntary and is related to the whole course of history and predestined from eternity.

*"To shed (or not to shed) the blood of his peoples.’