The 50th anniversary of the publication of "The Limits to Growth," in 1972, continues to generate interest. This is the original English version of the article by Jeffrey Sachs published in Italian on "Il Sole 24 Ore" -- courtesy of Susana Chacon. Above, the cover of the recent report to the Club of Rome, "Limits and Beyond", that re-examines the 1972 study and discusses its relevance for us

From Limits to Growth to Regeneration 2030

Jeffrey D. Sachs | May 26, 2022 | Il Sole 24 Ore

Fifty years ago, Italian business leaders in the Club of Rome gave a jolt to the world in their path-breaking report

Limits to Growth. That thought leadership continues today as

Italian business leaders launch Regeneration 2030, a powerful call for

more holistic, ethical, and sustainable business practices to help the

world achieve the Sustainable Development Goals

(SDGs) and the Paris Climate Agreement. The 50-year journey from

Limits of Growth

to Regeneration 2030 shows how far we have come in understanding the

critical challenges facing humanity, but also how far we still have to

go to meet those challenges.

The half-century since

Limits to Growth also defines my own

intellectual journey, since I began university studies at Harvard

University exactly 50 years ago as well. One of the first books that I

was assigned in my introductory economics course was

Limits to Growth. The book made a deep and lasting impression

on me. Here for the first time was a mathematical simulation of the

world economy and nature viewed holistically, and using new systems

dynamics modeling then underway at the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology (MIT).

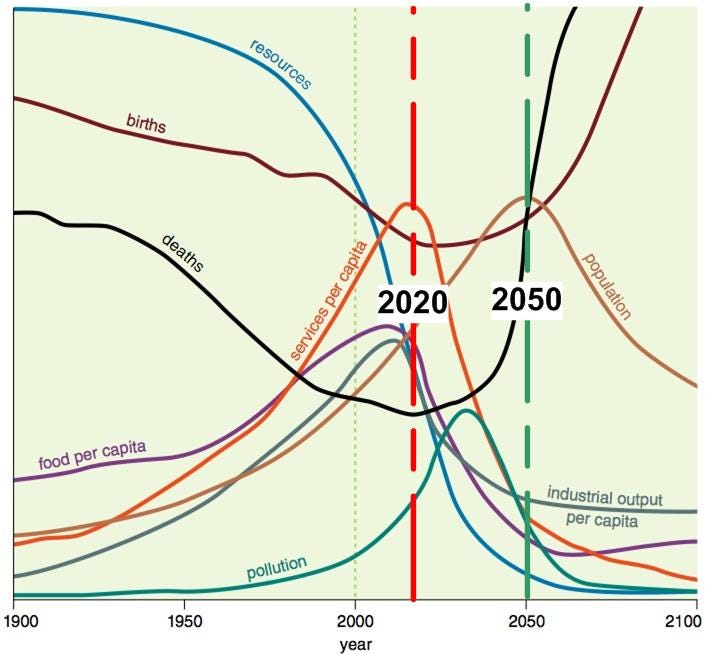

Limits to Growth warned that compound economic growth was on a

path to overshoot the Earth’s finite resources, leading to a potential

catastrophe in the 21

st century. My professor huffily

dismissed the book and its dire warning. The book,

the professor told us, had three marks against it. First, it was

written by engineers rather than economists. Second, it did understand

the wonders of a self-correcting market system. Third, it was written

at MIT, not at Harvard! Even at the time, I was

not so sure about this easy dismissal of the book’s crucial warning.

Fifty years later, and after countless international meetings,

conferences, treaties, thousands of weighty research studies, and most

importantly, after another half-century of our actual experience on the

planet, we can say the following. First, the growing

world economy is indeed overshooting the Earth’s finite resources.

Scientists now speak of the global economy exceeding the Earth’s

“planetary boundaries.” Second, the violation of these planetary

boundaries threatens the Earth’s physical systems and therefore

humanity itself. Specifically, humanity is warming the climate;

destroying the habitat of millions of other species; and polluting the

air, freshwater systems, soils, and oceans. Third, the market economy by

itself will not stop this destruction. Many of

the most dangerous actions – such as emitting climate-changing

greenhouse gases, destroying native forests, and adding chemical

nutrients to the rivers and estuaries – do not come with market signals

attached. Earth is currently treated as a free dumping

ground for many horrendously destructive practices.

Twenty years after

Limits to Growth, in 1992, the world’s

governments assembled at the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit to adopt

several environmental treaties, including the UN Framework Convention on

Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Convention on Biological

Diversity. Twenty years later, in 2012, the same governments

re-assembled in Rio to discuss the fact that the environmental treaties

were not working properly. Earth, they acknowledged, was in growing

danger. At that 2012 summit they committed to establish

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to guide humanity to safety. In

2015, all 193 UN member states adopted the SDGs and a few weeks later

signed the Paris Climate Agreement to implement the 1992 climate treaty.

In short, we have gone a half-century from the first warnings to today.

We have adopted many treaties and many global goals, but in practice,

have still not changed course. The Earth continues to warm, indeed at

an accelerating rate. The Earth’s average

temperature is now 1.2°C warmer than in the pre-industrial period

(dated as 1880-1920), and is higher than at any time during the past

10,000 years of civilization. Warming has accelerated to more than

0.3°C per decade, meaning that in the next decade we

will very possibly overshoot the 1.5°C warming limit that the world

agreed to in Paris.

A key insight for our future is that we now understand the difference

between mere “economic growth” and real economic progress. Economic

growth focuses on raising traditional measures of national income, and

is merely doing more of what we are already doing:

more pollution, more greenhouse gas emissions, more destruction of the

forests. True economic progress aims to raise the wellbeing of

humanity, by ending poverty, achieving a fairer and more just economy,

ensuring the quality education for all children, preventing

new disease outbreaks, and increasing living standards through

sustainable technologies and business practices. True economic progress

aims to transform our societies and technologies to raise human

wellbeing.

Regeneration 2030 is a powerful business initiative led by Italian

business leaders committed to real transformation. Regeneration aims to

learn from nature itself, by creating a more circular economy that

eliminates wastes and pollution by recycling, reusing,

and regenerating natural resources. Of course, an economy can’t be

entirely circular – it needs energy from the outside (otherwise

violating the laws of thermodynamics). But rather than the energy

coming from digging up and burning fossil fuels, the energy

of the future should come from the sun (including solar power, wind,

hydroelectric, and sustainable bioenergy) and from other safe

technologies. Even safe man-made fusion energy may be within technical

and economical reach in a few decades.

On my part, I am trying as well to help regenerate economics, to become a

new and more holistic academic discipline of sustainable development.

Just as business needs to be more holistic and aligned with the SDGs,

economics as an intellectual discipline needs

to recognize that the market economy must be embedded within an ethical

framework, and that politics must aim for the common good. Scientific

disciplines must work together, joining forces across the natural

sciences, policy sciences, human sciences, and

the arts. Pope Francis has spurred the call for such a new and

holistic economics by encouraging young people to adopt a new “Economy

of Francesco,” inspired by the love of nature and humanity of St.

Francis of Assisi.

Sustainable Development, Regenerative Economy, and the Economy of

Francesco are, at the core, a new way of harnessing our know-how, 21

st

century technologies, and ethics, to promote human wellbeing. The

first principle is the common good – and that

means that we must start with peace and cooperation. Ending the war in

Ukraine at the negotiating table without further delay, and finding

global common purpose between the West and East, is a good place for us

to begin anew.

Published in

Il Sole 24 Ore for the Trento Festival of Economics, June 4, 2022