"A scientist, Dr. Hans Zarkov, works night and day, perfecting the tool he hopes to save the world... His great mind is strained by the tremendous effort" (From Alex Raymond's "Flash Gordon")

We tend to see science as the work of individual scientists, maybe of the "mad scientist" kind. Great minds fighting to unravel the mysteries of nature with the raw power of their minds. But, of course, it is not the way science works. Science is a large network of people, institutions, and facilities. It consumes huge amounts of money from government budgets and private enterprises. And most of this money, today, is wasted on useless research that benefits no one. Science has become a great paper-churning machine whose purpose seems to be mainly the glorification of a few superstar scientists. Their main role seems to be to speak glibly and portentously about how what they are doing will one day benefit humankind, provided that more money is poured into their research projects.

Adam Mastroianni makes a few simple and well-thought considerations in his blog about why science has become the disastrous waste of money and human energy it is today. The problem is not with science itself: the problem is how we manage large organizations.

You may have experienced the problem in your career. Organizations seem to work nicely for the purpose they were built up to when they include a few tens of people, maybe up to a hundred members. Then, they devolve into conventicles whose main purpose seems to be to gather resources for themselves, even at the cost of damaging the enterprise as a whole.

Is it unavoidable? Probably yes. It is part of the way Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) work, and, by all means, human organizations are CASs. These systems are evolution-driven: if they exist, it means they are stable. So, the existing ones are those who managed to attain a certain degree of stability. They do that by ruthlessly eliminating the inefficient parts of the system. The best example is Earth's ecosystem: You may have heard that evolution means the "survival of the fittest." But no, it is not like that. It is the system that must survive, not individual creatures. The "fittest" creatures are nothing if the system they are part of does not survive. So, ecosystems survive by eliminating the unfit. Gorshkov and Makarieva call them "decay individuals." You can find these considerations in their book "Biotic Regulation of the Environment."

It is the same for the CAS we call "Science." It has evolved in a way that maximizes its own survival and stability. That's evident if you know just a little about how Science works. It is a rigid, inflexible, self-referencing organization refractory to all attempts to reform from the inside. It is a point that Mastroianni makes very clear in his post. A huge amount of resources and human efforts are spent by the scientific enterprise to weed out what's defined as "bad science," seen as anything that threatens the stability of the whole system. That includes the baroque organization of scientific journals, the gatekeeping control by the disastrously inefficient "peer review" system, the distribution of research funds by rigid old-boy networks, the beastly exploitation of young researchers, and more. All this tends to destroy both the very bad (which is a good thing) and the very good (which is not a good thing at all). But both the very good and the very bad threaten the stability of the entrenched scientific establishment. Truly revolutionary discoveries that really could change the world would reverberate through the established hierarchies and make the system collapse.

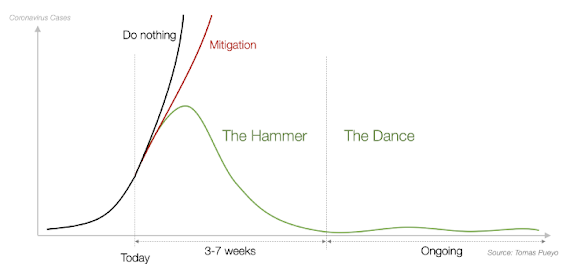

Matroianni makes these points from a different viewpoint that he calls the "weak links -- strong links" problem. It is a correct way if you frame Science not as a self-referencing system but as a subsystem of a wider system which is human society. In this sense, Science exists to serve useful purposes and not just to pay salaries to scientists. What Mastroianni says is that we should strive to encourage good science instead of discouraging bad science. What we are doing is settling on mediocrity, and we just waste money in the process. Here is how he summarizes his idea.